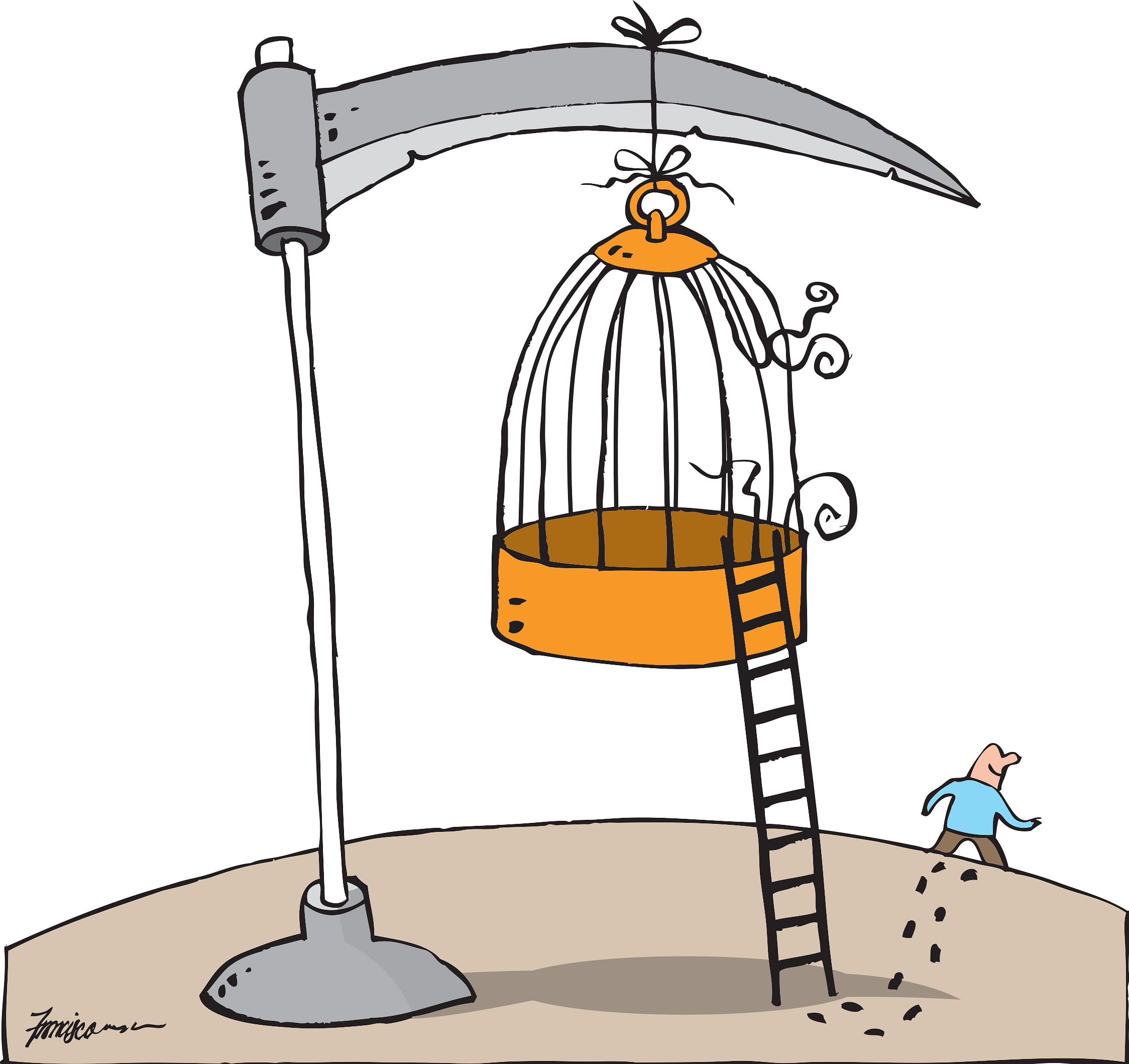

HIV: No longer a death sentence

Antiretroviral drugs have allowed HIV sufferers to lead normal lives but the stigma of the disease remains

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

C.T. watches his diet and works out every day. He spends 20 minutes on the treadmill and an hour lifting weights.

When the 52-year-old businessman told a close friend he is HIV-positive, the friend thought he was joking. Gym-toned and muscular, C.T. says he does not look like he has the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) that causes Aids.

In fact, he has lived with HIV for 25 years. "Having HIV is not a death sentence these days. When I was diagnosed in 1990, I was given six years to live. I am very fortunate and thankful to God," C.T. says.

Like others living with HIV/Aids in Singapore, he owes his extended years to the antiretroviral therapy drugs he has been taking every day since he was diagnosed.

The medication, which first emerged in the mid-1990s, is usually taken in combinations. These strong antiretroviral cocktails revolutionised the treatment of HIV. They suppress the virus that affects the immune system and allow people with HIV to live healthily.

But despite outward appearances of vitality, many persons with HIV continue to live secret lives, battled by old stigmas. HIV is mainly transmitted through sexual intercourse but the virus can spread in other ways, such as by sharing contaminated needles and through blood transfusion.

Last week, actor Charlie Sheen revealed he has been HIV-positive for at least four years. He started on antiretroviral treatment as soon as he found out and his physician, Dr Robert Huizenga, confirmed that the virus is at undetectable levels in Sheen's blood.

For C.T., living with HIV now is "a breeze" compared with before.

"So many friends died in the 1990s before the antiretroviral drugs came out and their parents didn't know they died of Aids. We kept going to funerals," says C.T., who lost about 15 friends then. He says he was infected by his partner then, a doctor who eventually died of Aids in his 30s.

Early in C.T.'s treatment, he felt nauseous, a side effect of the antiretroviral medication available then. For 10 years, an alarm on his watch went off every three hours to remind him to take his daily allotment of 15 pills.

Now, as antiretroviral drugs have improved, he takes only two pills once a day. "The quality of life has increased so much. Over the years, I feel even more normal."

Medical experts such as Dr Leong Hoe Nam says that HIV is now a "chronic condition".

Using diabetes as an analogy, Dr Leong, an infectious diseases physician at Mount Elizabeth Novena Hospital, adds: "The availabilty of antiretroviral drugs is like the availability of insulin for diabetics dependent on it. Immediately, it is a new lease of life. However, they remain dependent on them for life."

Unsubsidised drugs cost about $1,000 a month with newer drugs costing about $2,000 a month. Government subsidies are available. Many sufferers turn to cheaper generic drugs from Thailand which cost about $100 a month.

The newer antiretroviral drugs also do not have side effects such as nausea, anaemia, unusual dreams and depression, says Dr Leong, whose patients with HIV include professionals, blue-collar workers and gym instructors.

While condom use is encouraged, persons with HIV can have children. One of Dr Leong's HIV-positive patients delivered a healthy baby.

Prompt diagnosis is key.

"Should the disease be caught early and treatment started early, their life can be normal," says Dr Leong, adding that this extends to a normal life expectancy.

However, people do shy away from timely HIV testing.

"A significant number of persons who are HIV-infected do not know they are infected because they have not gone for a HIV test," says Professor Roy Chan, president of Action for Aids Singapore. "This is reflected by the high proportion of persons with late- stage disease at first diagnosis, around 50 per cent last year."

Last year, Action for Aids conducted 10,870 tests for HIV through anonymous counselling and testing.

Since antiretroviral therapies were introduced, the rates of opportunistic infections, which can take hold when the immune system is weakened by HIV, have fallen.

However, late diagnosis is still associated with an increased rate of deaths, studies have shown.

Early treatment with antiretroviral drugs gave S.A., a woman in her 60s, "a kind of freedom" after the devastating diagnosis in 2008, following a battery of tests done when she was hospitalised for tuberculosis.

Separated from her husband for decades, she says she caught HIV from her then-partner of five years.

While her treatment has rendered virus levels undetectable for the past four years, she has experienced how the misperceptions that have long surrounded HIV/Aids continue to affect sufferers.

S.A., who is a grandmother, feels tired after taking her antiretroviral pills, but wonders if that also has to do with ageing. She is active and independent: She babysits her grandchildren and travels alone to countries such as Indonesia and Vietnam.

On a trip to Bangkok in 2012, she even took an HIV test that came back negative, though her doctor later told her the virus remains in her body.

When she first realised she was HIV-positive, she felt the pain of "alienation" when she confided in her three adult children. They were scared and used Dettol to sterilise surfaces in her home while caring for her.

"When they Googled for information about the virus, they found out that HIV is not airborne. Neither can it be contracted when sharing food. Everyone started to relax, especially when they saw me getting better," says S.A. "Stigma can be lessened through more education."

For some persons with HIV, the benefits of antiretroviral drugs offer scant comfort.

About four years ago, Mr Tan, a manager in his 40s, went through a stormy period, which included frequent hospital visits because of a heart condition and repeated fainting spells.

His marriage had broken down, "not because of HIV", but partly because of the financial strain from his hospital bills. Following tests at a hospital, he was diagnosed with HIV.

A close colleague broke off contact after Mr Tan confided in him. With friends, he tried but failed to broach the topic of sexually transmitted diseases. He does not want anyone to see the labels of his HIV medicine.

No longer working, Mr Tan is living in a shelter for persons with HIV/Aids for five months because "here, everyone is the same, it is easier for us to talk".

He does not confide in his relatives, friends or colleagues.

He knows that the antiretroviral drugs he is on can extend life expectancy, but wonders when he will get full-blown Aids.

Divorced with a teenaged daughter whom he rarely sees, he dismisses the possibility of having another relationship in the future.

"When you work for a family, you have a target. I cannot have this target," says Mr Tan, who hopes to eventually return to work. "I'd be working only for my medication, to see doctors. What else can I expect?"

While relationships can be a thorny testing ground for some, others have found happiness unexpectedly.

For C.T., the virus brought him and his partner of 12 years, who has Aids, together. They met at a support group for persons with HIV/Aids.

"Ironically, HIV has brought us closer together. We treasure each other more because there's a commitment in terms of a long-term relationship. We look after each other if we are ill," he says.

•World Aids Day is marked on Tuesday.