Living with cancer: An ST series

Liver cancer difficult to treat due to huge tumour variations

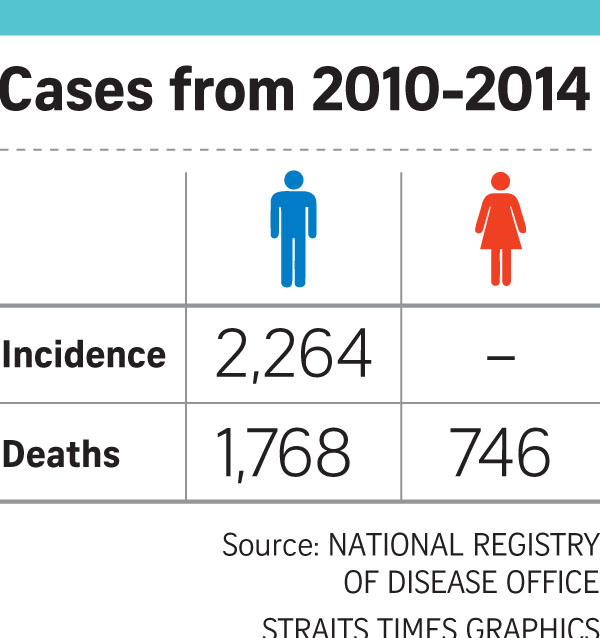

It is the fourth most common cancer suffered by men, although it is not as common in women. However, it is the third-biggest cause of cancer death in men, and the fourth in women.

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

To experts like Prof Chow, it does not help that liver cancer, although not uncommon, is not yet well understood.

PHOTO: NATIONAL CANCER CENTRE SINGAPORE

The problem with liver cancer is that each tumour is unique.

Even within the same person, different parts of a tumour can have a different genetic make-up, making it tough for doctors to find a treatment plan that works against the whole.

And it does not help that this cancer, although not uncommon, is not yet well understood.

Part of the reason is that 80 per cent of cases are found in the Asia-Pacific, rather than in the West where the most cutting-edge research is done, said Professor Pierce Chow, who is from the surgical oncology division at the National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS).

He added: "Liver cancer, for the longest time, was really the cancer of poor people in the Third World."

The lack of research in this area means that existing treatment for it is limited.

The standard drug used for patients with this disease, called Sorafenib, does not work on many people. Surgery to remove the tumour is often a stopgap measure, as 95 per cent of cancer recurrences happen within three years.

But doctors in Singapore are trying to change this by learning more about the different sub-types of liver cancer, which could pave the way towards more personalised treatment.

Prof Chow and his team, for instance, are collecting the tumours cut out of patients during surgery and analysing them in detail.

If his patients return because their cancer has recurred, he could already know which existing drugs work against their particular tumour.

Currently, explained Associate Professor Dan Yock Young, who is from the National University Hospital's gastroenterology and hepatology division, treating liver cancer can be a little like flying blind.

Unlike other cancers, biopsies are not often done since any sample might not be representative of the entire tumour.

"It's almost like we are treating a black and white shadow, while others have moved on to colour televisions," Prof Dan said.

"We want to put them into sub-classifications, so that we have a better idea in terms of predicting the overall outcome."

Currently, treatment options include liver transplantation and surgery to remove part of the liver.

Doctors have also developed a technique known as transarterial chemoembolisation - in which chemotherapy drugs are injected into the liver and block the blood supply to the tumour, after which it can be burned off.

If these do not work, there are oral chemotherapy medications.

In Singapore, liver cancer is the fourth most common cancer in men, and the third most likely to kill. Some 2,264 cases of this cancer were reported between 2010 and 2014.

It is also the fourth most common cause of cancer death in women, although it does not make an appearance in the list of common female cancers.

Liver cancer is traditionally associated with the hepatitis B virus, which is estimated to have infected between 5 and 10 per cent of the population in East Asia.

Carriers of the virus, said Dr Cheah Yee Lee, a general surgeon at Gleneagles Hospital, are a hundred times more likely to get liver cancer compared to those who are virus-free.

In Singapore, all those born after 1985 have been vaccinated against hepatitis B - although that still means a good proportion of the population is susceptible.

Rising obesity numbers also mean that non-alcoholic fatty liver disease has become a new culprit.

When fat accumulates in the liver, Dr Cheah explained, the liver can become inflamed or hardened, which could eventually lead to cancer.

This can complicate treatment further, because doctors might deem it unsafe to put further stress on the liver when the organ is already not doing well.

"Liver cancer differs from other cancers in this regard - the treatment and prognosis of liver cancer is also dependent on the underlying liver disease and function," Dr Cheah said.

Those who want to reduce their chances of this cancer can do so by leading a healthy lifestyle, which makes them less likely to get fatty liver disease.

This includes not smoking and, interestingly enough, drinking more coffee.

"Avoid oily foods that add on to metabolic stress," Prof Dan said. "We think that fish and vegetables also help."

•For further enquiries on liver cancer, please call the National Cancer Centre Singapore helpline on 6225-5655 or e-mail it at cancerhelpline@nccs.com.sg

You can also contact the National University Cancer Institute, Singapore on 6773-7888 or e-mail it at ncis@nuhs.edu.sg.

•Next week: Skin cancer

Find out more about cancer and how to fight it on ST's Fighting Cancer microsite.