Giving marine pests the slip

A $25 million, five-year national programme dedicated to marine science research has been launched by National Research Foundation in collaboration with National University of Singapore. Audrey Tan reports on some marine science research in Singapore and why it is important.

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

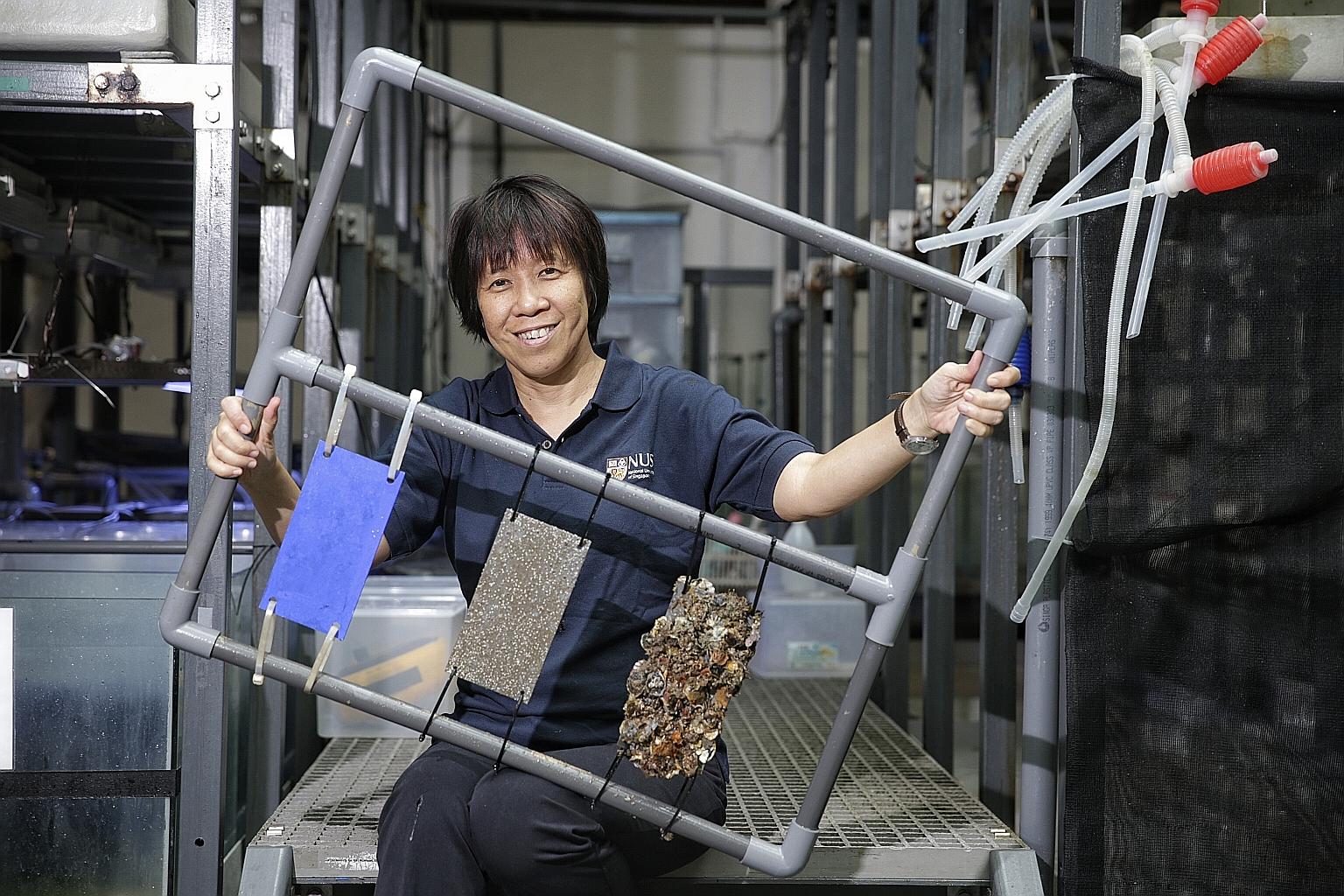

Dr Teo with some samples (from left): a panel with protective coating to prevent biofouling; a panel without the coating after a month of exposure to marine pests; and a panel without the coating after a year of exposure.

ST PHOTO: KEVIN LIM

The Asian green mussel, or kupang in Malay, is a delicacy enjoyed in this region, but in places like America they are considered pests.

The original birthplace of these creatures is the Indo-Pacific region, where Singapore is located.

But now they have crossed the Pacific through South America to Florida by "hitchhiking" on the hulls of ships or ballast tanks, which are filled or emptied of seawater to keep a ship stable.

The kupang is a hardy mussel that can withstand a range of temperatures and salinity. It attaches to hard surfaces, forming clumps in places such as on seawater intake pipes and vessels. Such undesirable marine growth on man-made surfaces is known as biofouling.

These clumps reduce vessel speeds by more than 10 per cent owing to drag, and increase fuel consumption of ships when they power up to overcome it.

The Asian green mussel, like other marine pests, can also damage engines and propellers and upset native ecosystems.

Singapore, like many coastal cities with urban harbours, is vulnerable to such invasions, which could hurt its status as the world's top transhipment hub.

Already, another mussel species, Mytilopsis sallei, or the false zebra mussel - an invasive marine pest from the Caribbean - has established itself on Singapore's concrete walls and monsoon drains.

Dr Serena Teo, deputy director for research at the National University of Singapore's Tropical Marine Science Institute, leads a biofouling research team that has been studying, since 2002, the biology of marine pests such as barnacles and tubeworms.

Among other things, they investigate how these creatures respond and adhere to materials, as well as how these biologically active materials may affect the environment.

In the past 10 years, Dr Teo and her team - together with chemists from NUS and the Agency for Science, Technology and Research - have developed new environmentally safe anti-fouling additives and materials, which prevent marine pests from latching on to vessels.

This work has resulted in several patents and findings that are useful for the marine industry.

Said Dr Teo: "It is internationally recognised that fouling in tropics, especially in Asia, is very aggressive. This is not unexpected as tropical Asia has the highest marine biodiversity in the world.''

She added: "With the expertise in our research institutions and local industry, we have an unprecedented opportunity to expedite the development of new anti-fouling technology."

Her ongoing work illustrates the importance of marine science research in Singapore, a field that will get a boost from a $25 million, five-year programme announced yesterday.

This marine science research and development programme, launched by the National Research Foundation with NUS, will include research into emerging environmental challenges such as climate change and urbanisation.