Close encounters of the crawly kind

With Halloween round the corner, snakes and spiders are likely to come to mind. But these animals might not be as scary as some people think. Audrey Tan highlights research being done on some of these oft-misunderstood creatures, and the lessons that they can teach us.

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Why reticulated pythons are friends, not foes

The fear of snakes may hark back to biblical times, but reticulated python researcher Mary-Ruth Low, 27, believes they are just misunderstood, as most pose no direct threat to humans unless provoked.

For 21/2 years, she studied non-venomous snakes, tracking the movements of 28 of them, in a bid to understand more about the world's longest snake, which can grow up to 3m here.

"People in urban societies like Singapore often panic when they see a reticulated python, thinking it might attack them. But reticulated pythons do not see humans as food or prey," said Ms Low, a conservation and research officer at Wildlife Reserves Singapore (WRS).

"It is usually when they feel threatened, like when they are being pelted with rocks, or slashed with a stick, that they will react. A snake, being a limbless animal, can defend itself only by biting," said Ms Low.

There are more than 70 snake species in Singapore, but the reticulated python is one of the most commonly encountered as these reptiles seem to thrive in urban areas. As recently as in July, for example, a 2m-long one was found in a coffee shop in Ang Mo Kio.

Ms Low's findings could shed light on the reason. Of the 28 reticulated pythons that were rescued, tagged with a radio transmitter, and re-introduced into a remote vegetated area, she discovered that about 60 per cent of them moved to forest fringes and into urban areas, using drains as a "highway" for getting around in their search for food. "The main driver for them seemed to be the availability of prey like rodents," said Ms Low, who started her project in 2013 as a research assistant studying the spatial ecology of reptiles at the National University of Singapore (NUS). Her study was funded by NUS and WRS.

Their choice of food means reticulated pythons play an important role in keeping the population of pests, such as rats, low in urban areas.

The 28 snakes Ms Low tracked were "conflict" pythons - they had been found in or near homes, and people had called organisations such as wildlife rescue group Animal Concerns Research and Education Society (Acres) to complain about them. Ms Low said Acres receives calls about pythons at least once a day.

Once rescued, the pythons were taken to the zoo, where they were tagged with thumb-sized radio transmitters that emit a signal.

The animals were then released into areas far away from humans.

Armed with an antenna and a radio receiver no bigger than a shoebox, Ms Low spent the next 11/2 years tracking them. She would first go to the site where a tagged snake was last spotted, and widen her search in concentric circles until she got a ping on her receiver.

At the time, she was trying to find out how reticulated python movement was affected by translocation, or being moved away from its original site. One thing she was looking for was whether the snakes would return to where they were found.

"In general, animals have home ranges, which refer to the areas in which they regularly travel to look for food or mates," said Ms Low. "In many translocation cases, especially for mammals, the animals were observed to move in the direction of their home range."

If the pythons had the same homing instinct, it would make translocation an ineffective way of reducing human-animal conflict, as the animals would return to the areas where they were seen as a nuisance. But her study showed that they did not have such an instinct. "The availability of prey seems to be the driving factor of their movement," she said.

Mr Sankar Ananthanarayanan, co-founder of the Herpetological Society of Singapore which studies reptiles and amphibians, said Ms Low's research is valuable as it helps people understand how reticulated pythons have been adapting to the developing urban landscape.

He added: "It highlights the importance of educating the residents of Singapore, particularly those living near green spaces, to avoid human-wildlife conflict."

Ms Low said those who spot a reticulated python should get people away from the area and call Acres.

Sacred serpents or reason to recoil?

In the Bible, it is the wily serpent that gets Adam and Eve thrown out of Paradise. The Judeo-Christian world is not the only one that sees snakes in an negative light.

And when they are not being vilified in stories, they are hunted for their supposed aphrodisiac properties.

For instance, the Japanese believe that habushu, wine made from a snake known as the habu, can impart energy and mitigate male sexual dysfunction. Its effectiveness remains unproven.

In Singapore, there are more than 70 species of snakes, of which only seven are venomous, said Mr Sankar Ananthanarayanan, co-founder of the Herpetological Society of Singapore which studies reptiles and amphibians.

They are the king cobra, spitting cobra, banded coral snake, blue coral snake, banded krait, Wagler's pit viper and mangrove pit viper.

"But none of these snakes want anything to do with humans, and just want to be left alone," said Mr Sankar.

"Many people have misconceptions about snakes, that they are all venomous man-eaters. Honestly, it's far from the truth."

In other parts of the world, however, snakes have a better reputation.

In India, for instance, snakes are worshipped as gods, and have their own special temples.

The universal symbol of medicine, the snake-coiled Rod of Asclepius, is also considered a sign of therapeutic renewal.

The ancient Greeks saw snakes as sacred and used them in healing rituals - believing that their venom had healing properties, and that their skin-shedding symbolised rebirth and renewal.

Pesticide-resistant cockroach could hold key to pest control

A glimpse of a cockroach may send shivers up one's spine but Dr Tang Qian, 27, had thousands of them in his laboratory when he was studying the German cockroach.

It is one of three cockroach species considered pests in Singapore, and it is the hardest to kill. Not only is it resistant to pesticides, but the German cockroach also lives in cracks and crevices, rarely venturing out.

This small cockroach, typically about 1.1cm to 1.6cm long, is found widely in buildings, but is a particular menace in restaurants, food-processing facilities, hotels, and institutional establishments such as nursing homes.

The Australian and American cockroaches - the other two cockroach species considered pests - can commonly be seen scurrying about in drains or public areas. Little is known about the German cockroach, despite its ubiquity not just in Singapore, but in countries around the world, such as China.

A new study by Dr Tang, a research fellow at the department of biological sciences in the National University of Singapore's (NUS) science faculty, has shed light on how German cockroaches came to be such successful pests.

His findings could spur future research into ways of dealing with infestations.

Dr Tang's study involved a genetic analysis of 599 German cockroaches from nine cities in China.

It showed that there were two genetic clusters in northern and southern China, implying two likely expansions of the cockroaches there, said Dr Tang, who worked with scientists from China and Australia on the study.

"Both expansions were linked to the improvement of indoor heating," said Dr Tang, who did the study as part of his doctoral research. He received his PhD from NUS in July.

The first spread was when central heating systems in northern China were built during the 1960s.

The second took place in the 1990s, when air-conditioning systems, which function as heaters during the winter, were built in southern China.

"Studies have shown that cockroaches dislike temperatures below 15 deg C," said Dr Tang. "The German cockroaches need to establish and grow to considerable abundance to spread. Indoor heating helps to maintain the population during winter, when they would otherwise die."

He next hopes to learn more about the German cockroach's phylogeny - the origins of the species and other closely-related species - through mapping out its genetic structure. "By learning more about its genetic make-up, we could learn why it may be more resistant to pesticides, and perhaps develop more effective pest-control methods," said Dr Tang.

Innovative Pest Management technical director Hadi Hanafi said that while the American cockroach can be killed easily by fumigation or spraying treatment, this is not the case with German cockroaches. Adults carry the egg case around until the eggs are close to hatching, he said.

"This makes them scatter easily, which makes them hard to kill. If scientific studies could help us learn more about them, perhaps more effective treatment methods could be developed."

ONLINE

For more about the cockroach species found in Singapore, go to http://str.sg/4YxC

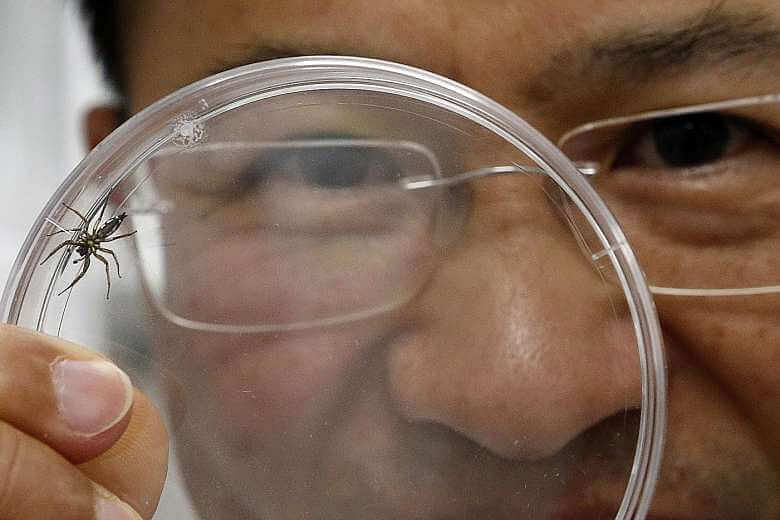

Spider study can light the way to new tech

Spiders and cobwebs are fixtures in haunted houses, but not all of these eight-legged animals are creatures of the night.

Take it from Singapore's own Spider-Man, National University of Singapore (NUS) Associate Professor Li Daiqin, who recently discovered that the Cosmophasis umbratica, a species of the jumping spider found here, uses the sun's ultraviolet (UV) rays for communication and to find that perfect mate.

Prof Li, who is from the department of biological sciences at the NUS Science Faculty, found that UVA and UVB light, which humans cannot see, are important to the jumping spider.

Only male jumping spiders can reflect UV light. In the spider world, this works similarly to how, say, peacocks, like many males in the animal kingdom, are more brightly coloured than their female counterparts.

Prof Li found that while UVA is an indicator of gender, UVB reflectance tells the quality of the male. When UVA was filtered out, female jumping spiders behaved as though the males they encountered were females, while males tried to court males.

But when the female spiders were shown two male spiders - one under normal light and the other under light with UVB filtered out - females initially started moving toward both males. Interestingly though, they showed more interest in the male with UVB reflectance, compared to the one without.

Prof Li said the "attractiveness" of the male spider depends on how much UVB is reflected. UVB reflectance is a structural colour, which refers to how light is reflected off microscopic hairs and scales of the spider to produce what humans see as iridescence. In comparison, colours like red, orange and yellow are pigmented colours.

Because of the way the microscopic structures are arranged, and depending on the angle that the UV light hits them, structural colour may appear different from different angles. This finding could help with the development of defence technology, or paint pigments that do not fade, said Prof Li.

Spider expert Joseph Koh said structural colour is a subject that has attracted some attention from scientists and engineers working on biomimicry - the process of looking for nature-inspired solutions to human challenges.

"One of the most exciting works is focused on a tarantula known as the Singapore blue.

Its hair has a complex nanostructure that produces a non-reflective but consistently vibrant blue coloration regardless of the angle you look at it.

"If we can artificially replicate, emulate or mimic the nanostructure, we will be able to produce colour pigments that will never fade, or reduce glare on smartphone screens and wide-angle television monitors."