BY INVITATION

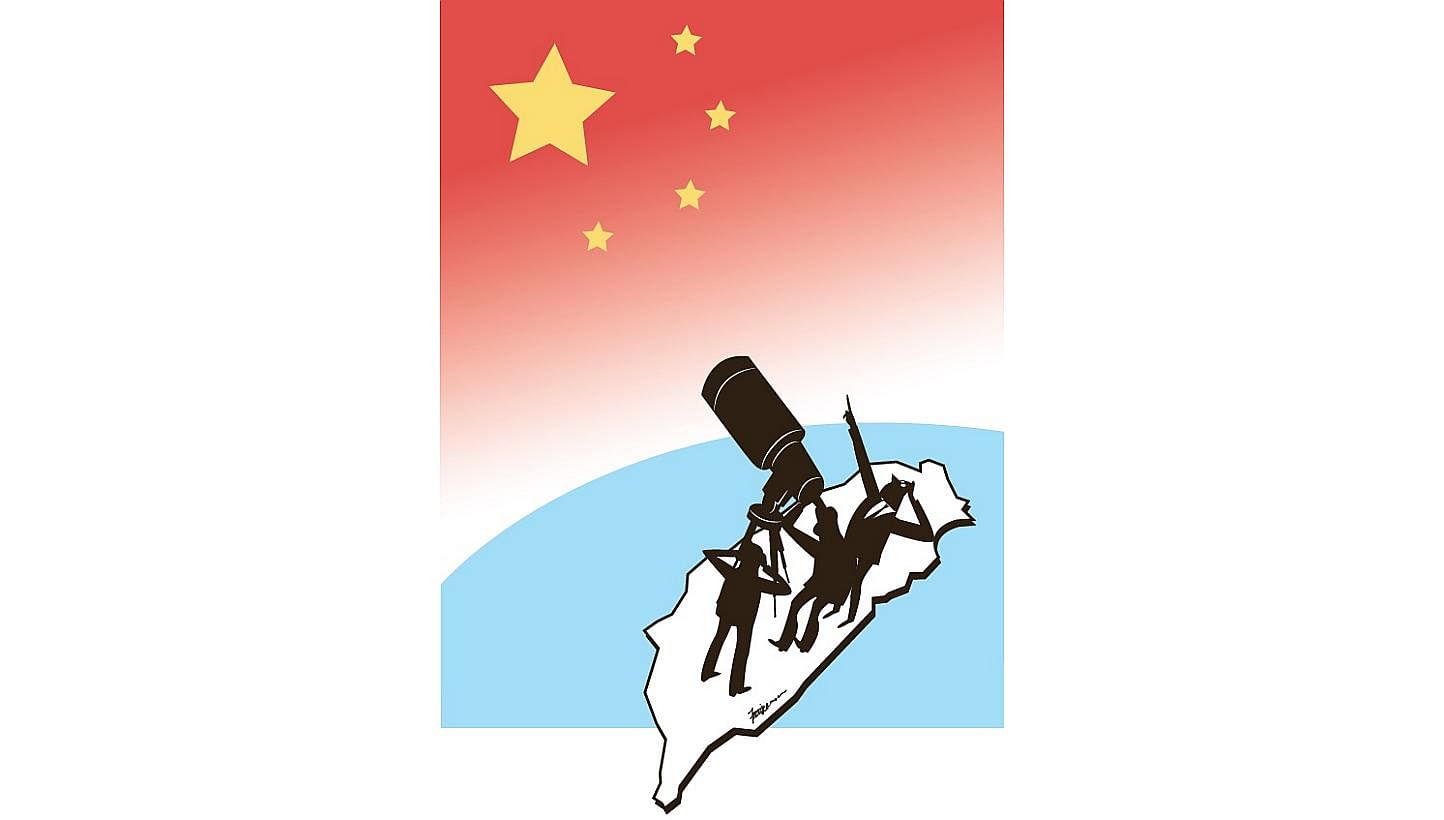

The harsh reality that Taiwan faces

Taiwan's polls next year could usher in a president more assertive to Beijing, which could in turn respond by taking a tougher line.

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

-- ST ILLUSTRATION: MANNY FRANCISCO

IT IS time to start worrying about Taiwan again.

In the past few years, it has slipped quietly into the background as tensions in the East China Sea and South China Sea have posed more urgent threats to regional peace and stability. But now old questions about Taiwan's longer-term future are re-emerging, and so are old fears that differences over Taiwan could rupture United States-China relations and drive Asia into a major crisis.

Taiwan's status has been a highly sensitive issue between Washington and Beijing ever since 1949, when defeated nationalists withdrew to the island as the communists swept to power in the mainland. The differences were papered over only when US-China relations were opened up after 1972. Taiwan was left in an awkward limbo, neither accepting Beijing's rule nor seeking recognition as an independent country.

Beijing has never wavered in its determination to bring Taiwan eventually under its rule, while America's Taiwan Relations Act enshrines its commitment to support Taiwan in resisting pressure from Beijing to reunify.

In the 1990s, after Taiwan became a vigorous democracy, presidents Lee Teng-hui and Chen Shui-bian started to push the boundaries of this status quo, seeking a more normal place for Taiwan in the international community. This infuriated Beijing and escalated tensions between China and America.

These tensions eased when, in 2003, then US President George W. Bush made it clear that the US would not support any Taiwanese push to change the status quo.

After President Ma Ying-jeou took office in 2008, he stepped back from his predecessors' challenge to the status quo, and instead sought to build relations with Beijing, especially by encouraging commercial ties, which have led to the two sides of the Taiwan Strait becoming deeply intertwined economically.

And China was happy to replace sticks with carrots in dealing with Taipei, apparently expecting that economic integration would eventually pave the way to political reunification, perhaps under the "one country, two systems" formula that Beijing applies to Hong Kong.

But that hope received a severe blow just a year ago, when Mr Ma's plans for closer economic links with the mainland sparked massive "Sunflower" demonstrations in Taipei by mainly young people who feared that economic entanglement would lead inexorably to precisely the political reunification that Beijing so clearly wants and expects. Then late last year, Mr Ma's policy of ever-closer economic relations suffered further repudiation by voters in a crucial round of municipal elections.

It is now widely expected that when Mr Ma's term as president ends next year, he will be replaced by a new leader who will be less accommodating to Beijing. While few expect that any future leader from either the Kuomintang or the Democratic Progressive Party will return to policies as provocative to China as those of Mr Lee or Mr Chen, the new leader will almost certainly be more assertive than Mr Ma has been.

That naturally alarms Beijing, and there is a risk that it will respond by taking a tougher line, looking for new ways to pressure Taipei into accepting the mainland's authority.

China's new leadership under President Xi Jinping seems increasingly impatient to resolve what it sees as the last vestige of China's centuries of humiliation and increasingly confident of its growing power to act with impunity. Already there are signs that its stance on Taiwan is hardening.

That, in turn, poses a huge potential problem to the rest of the region and especially to Washington. The US has always declared its commitment to support Taiwan if China tries to compel reunification. The credibility of this commitment has now grown even more important because it is seen as a crucial test of America's ability to preserve the old US-led order in Asia in the face of China's relentless push for a bigger role.

But the stark reality is that these days, there is not much the US can realistically do to help Taipei stand up to serious pressure from Beijing.

Back in 1996 when they last went toe-to-toe over Taiwan, the US could simply send a couple of aircraft carriers into the area to force China to back off. Today the balance of power is vastly different: China can sink the carriers, and their economies are so intertwined that trade sanctions of the kind the US used against Russia recently are simply unthinkable.

This reality does not yet seem to have been understood in Taiwan. The overwhelming desire on the island is to preserve its democracy and avoid reunification by preserving the status quo. But it understands that China's patience is not inexhaustible - eventually China wants to get Taiwan back.

Taiwan also understands that it cannot stand up to the mainland by itself, but it hopes that by slowly expanding its international status and profile within the status quo - without seeking independence - it can build support among regional countries as well as from the US, which will help it resist Beijing's ambitions for eventual reunification.

Alas, this seems an illusion. There is a real danger that the Taiwanese overestimate the international support they can rely on if Beijing decides to get tough.

No one visiting Taipei can fail to be impressed by what the Taiwanese have achieved in recent decades, not just economically but also politically, socially and culturally. But the harsh reality is that no country is going to sacrifice its relations with China in order to help Taiwan preserve the status quo. China is simply too important economically, and too powerful militarily, for anyone to confront it on Taiwan's behalf, especially when everyone knows how determined China is to achieve reunification eventually.

Even more worryingly, this reality does not yet seem to have sunk in in Washington, where leaders still talk boldly about their willingness to stand by Taiwan without seriously considering what that might mean in practice. Any US effort to support Taiwan militarily against China would be almost certain to escalate into a full-scale US-China war and quite possibly a nuclear exchange. That would be a disaster for everyone, including, of course, the people of Taiwan itself - far worse than reunification, in fact.

That is why Taiwan and its friends and admirers everywhere have to think very carefully about how to handle the dangerous period that lies ahead and to consider what is ultimately in the best interest of the Taiwanese people, as well as the rest of us. The conclusions will be uncomfortable, but inescapable.

stopinion@sph.com.sg

The writer is professor of strategic studies at the Australian National University in Canberra.