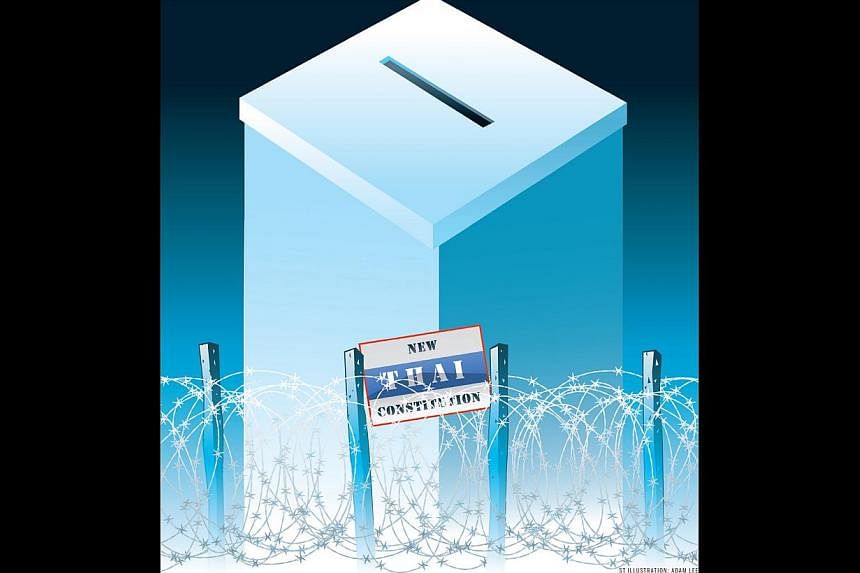

Thailand's ongoing Constitution-drafting process is increasingly fraught with controversy and downside risks.THAILAND'S ongoing Constitution-drafting process is increasingly fraught with controversy and downside risks.

It appears as if the country is going around in circles.

The military government that took power after the May 2014 coup has appointed a new panel to draft a charter for a new Constitution. According to the Bangkok Post, the Constitution Drafting Committee (CDC) is expected to submit the first draft of the new Constitution to the National Reform Council (NRC) for consideration by April 17. The final draft is expected to be ready to be made into law in September, and possible elections held next February.

But so far, the proposed draft charter contains elements from an authoritarian past that shift power from elected representatives to unelected appointees.

Since the main purpose of any acceptable and legitimate Constitution in any electoral democracy is to find a balance between popular representation for the electorate and institutional restraint from watchdog agencies, the draft is predictably meeting resistance from political parties and activists.

Halfway through the drafting process, the new Thai charter is being outfitted with too many checks without sufficient balance. Unless substantially revised, it is likely to lead the country into a new round of mounting political tension and probably turmoil down the road.

History of Constitution drafts

In recent times, Thailand's constitutional crafting has tended to follow an unsteady but largely linear trajectory.

Past Constitutions in military-dominant eras for much of the post-World War II period always made the Senate an appointed Upper Chamber to counterbalance the elected Lower House.

In 1991-92, when a disguised military dictatorship came to power after a coup and an election, this constitutional pattern shifted, owing to previous decades of development and modernisation.

Led by a swelling middle class, growing calls for a "full" democracy and a more democratic charter led to the reform-oriented and broad-based 1997 Constitution, featuring a fully elected Senate, a prime minister who had to be an elected member of Parliament, and a parliamentary presidency that resided with the elected Lower House, not the unelected Senate as in the past. Smaller parties were decimated in favour of larger ones.

The executive branch was strengthened to promote government stability and effectiveness. The checks and accountability mechanisms resided in a handful of newly mandated agencies, such as the Election Commission, National Anti-Corruption Commission and Constitutional Court.

The 1997 charter worked as designed for a short while, until it hit a brick wall embodied in the political party machine and vast wealth and personal networks of former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra. Eventually, the 1997 charter was penetrated and captured by Thaksin-linked vested interests and partisans. It was the most popular and arguably still Thailand's best Constitution because of its inclusiveness, bottom-up mandate and broad consensus.

But it was abolished after a military coup in 2006 ousted Thaksin. The constitutional pendulum has been swinging the other way in complete reversal since.

A year after the 2006 coup, a new Constitution came into place that made the Upper Chamber half-appointed and half-elected. The executive branch was weakened. More checks and accountability mechanisms were imposed.

The judiciary gained more authority at the expense of elected representatives. It became easier to dissolve parties and ban politicians.

Yet all that was not enough to put down Thaksin's resilient appeal as his party machine kept winning at the polls, partly because the opposition Democrat Party offered no attractive alternative. The Thaksin party machine topped Thailand's most recent election in July 2011 when his sister, Yingluck, led Pheu Thai party to a landslide win with an overall majority.

Back to appointments

Not having swung far enough, the anti-Thaksin pendulum in charter design appears to be going farther.

Under the proposed new charter, the 200-member Upper House Senate will consist of unelected members. The prime minister will also no longer have to be an elected lawmaker.

If the change goes through, the Senate is poised to return to its fully appointed pre-1997 versions, dominated by so-called professional groups and columns that will inevitably come from lobbying and jockeying at the top echelons without popular participation.

The prime minister will no longer have to be an MP. A clutch of assemblies are to be appointed to scrutinise politicians' and Cabinet ministers' performances to prevent their corruption.

MP candidates will not have to belong to parties, and a mixed-member proportional voting system is geared up to dilute big political parties in favour of smaller ones.

The envisaged government from this charter will be dominated by smaller parties that make coalitions unwieldy and unstable, as in the pre-1997 past.

Charter lessons

The lesson from Thailand's various charters is that constitutional provisions and institutional design can only go so far in producing intended outcomes. Ultimately, a Constitution must provide general principles, not detailed clauses, of democratic governance that derives from a popular mandate based on representation and restraint that go hand in hand.

Yet it is understandable that Thailand's current constitutional design is premised on a distrust of elected representatives.

Thai politicians have been disappointing at best and unscrupulous and abusive at worst. But all who engage in politics eventually become politicians. Demonising politicians will only exacerbate the Thai predicament because no fresh new faces will enter the electoral fray and because all future rulers of Thailand will have to engage in politics and become politicians.

It is one thing to distrust politicians but it is abhorrent and probably unsustainable in any country to disregard citizens' ability to see and judge matters for themselves.

There is a top-down premise inherent in Thailand's current Constitution-drafting that the few know better and more than the rest. In the past, this arrangement did not pose problems because the Thai masses and vast majority of the Thai citizenry were not as politically conscious and connected to the electoral system. The Thai masses now count more than ever, and they know it. Their voices will have to be accommodated and recognised if Thailand is to regain a new balance.

Anchoring the new Constitution firmly on citizenship inclusivity would lead to the second lesson in Thailand's charter experience.

In the end, rules do not deliver victory and overcome opponents. Those in Thailand who support new rules to keep Thaksin's camp at bay will have to learn to take power and claim legitimacy by winning at the polls.

It is a pity that the pro-coup and anti-Thaksin forces have been unwilling to play fair and square in the constitutional framework and electoral arena. They have the ability to win if they work hard enough to gain popular trust and support.

As it has unfolded thus far, the Constitution-drafting process is likely to produce a problematic document that is likely to lead to more tension and turmoil due to a lack of balance between representation and restraint.

Thailand's constitutional answers should focus more on representation and place more care and caution on restraint. Swinging the constitutional pendulum too far the other way raises the risk of a backlash that no one wants to see in a country that has already endured a decade of two coups and persistent political crises.

The writer teaches International Political Economy and directs the Institute of Security and International Studies at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok.