Akshita Nanda, Arts Correspondent

New prize for fiction raises $20,000 question

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

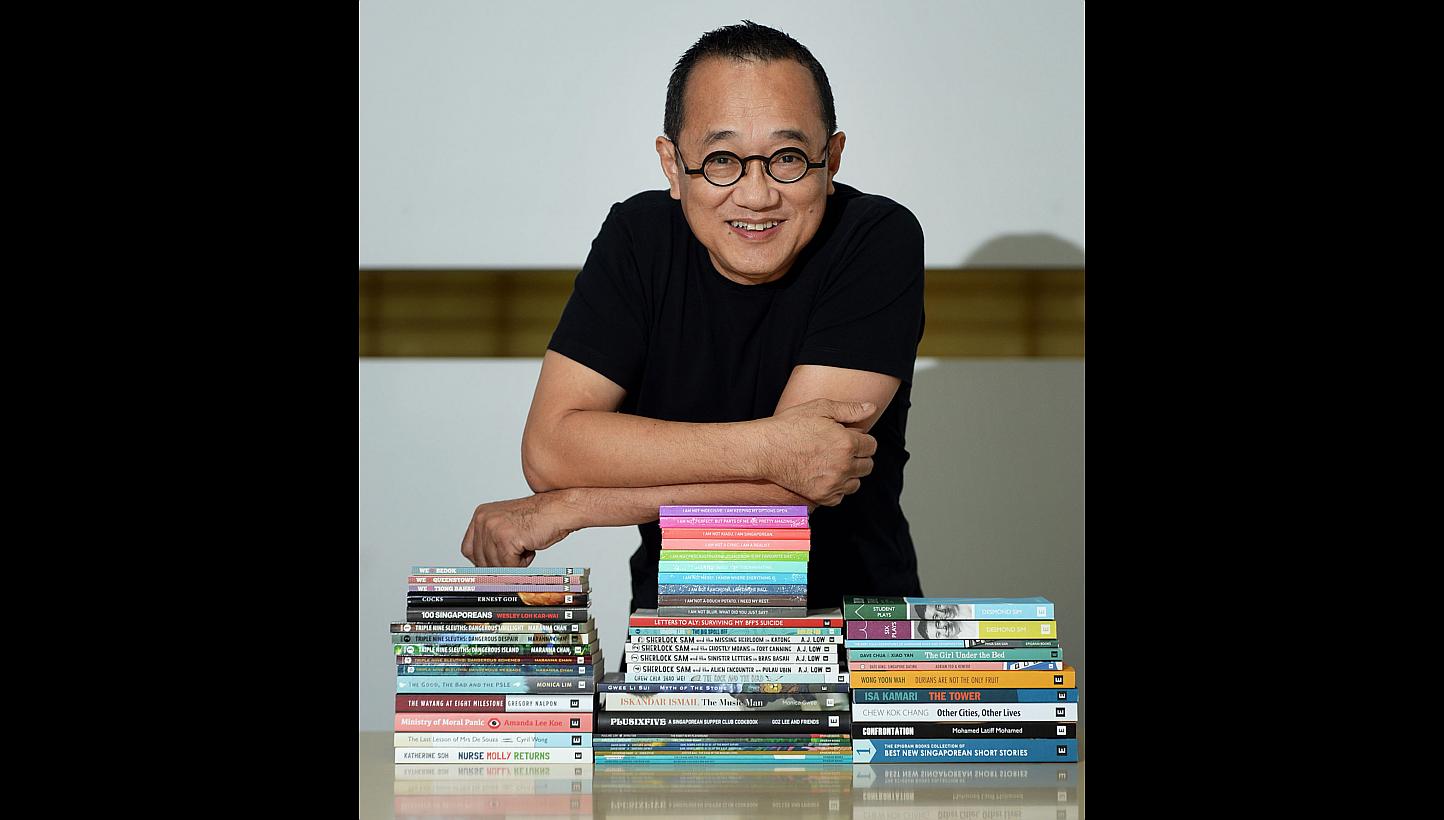

The $20,000 prize by Epigram Books, founded by Mr Edmund Wee (left), is the richest one here for English fiction.

ST FILE PHOTO

The literary industry in Singapore turned a page this month as a local publisher announced the country's richest prize for English fiction, unsupported by government grants or other sponsors.

The $20,000 Epigram Books Fiction Prize is the first offered here by a relatively small player, and is the only one for an unpublished novel.

Publisher Edmund Wee says his imprint, set up in 1999, is in the red, but still spends about $1 million a year on bringing out about 50 books - the cash cow is his separate design and pagesetting firm Epigram.

The new award has created a stir at home and overseas and was even written up on the Man Booker Prize blog on March 13. No other Singapore literary prize has managed the same in the past five years.

Part of the reason for this interest is that the Epigram Books Fiction Prize is twice the value of the next largest literary awards here, the biennial Singapore Literature Prize, revamped last year to offer $10,000 each for the best in fiction, non-fiction and poetry published in any of Singapore's four official languages.

The biennial Golden Point Awards for unpublished short stories and poetry in Chinese, English, Malay and Tamil also offer $10,000 in each category, split between a cash award and a grant for training and development.

The Singapore Literature Prize and the Golden Point Awards are offered by the National Arts Council and administered by the National Book Development Council of Singapore. The latter also administers $10,000 biennial awards for unpublished picturebooks and children's fiction, sponsored by the Asian arm of international publisher Scholastic Books.

But the Epigram Books Fiction Prize has the heart-stirring overtone of a maverick gamble. Money talks, and the prize speaks of confidence in writing from Singapore, which has enjoyed a resurgence since 2011, in part because of government grants for arts creation. Among them are a maximum $35,000 creation grant from the National Arts Council for the literary arts, to support new writing or translations over a period of up to 18 months. The country's highest arts honour, the Cultural Medallion, also comes with $80,000 to support a recipient's next work.

That is not the only reason publishers are now bringing out dozens of books of fiction and poetry a year, compared with a trickle in the 1990s and the 2000s. The other is competition. More independent book publishers are in the market now, investing their own assets in new writing.

Monsoon Books, Ethos Books, Math Paper Press, Epigram Books and Bubbly Books are publishing in genres from detective fiction to literary thrillers to young-adult zombie novels.

Despite the proliferation of titles, financial rewards are hard to reap. Ethos Books and Epigram Books often tap design and pagesetting services to fund their titles.

Math Paper Press is associated with a bookstore, Books Actually, so founder Kenny Leck prints only what he knows he can sell.

His authors often plough their royalties back into his publishing efforts - poet Joshua Ip told The Straits Times that his share of last year's Singapore Literature Prize would go to bringing out the works of other poets.

So there is a pool of people dedicated to encouraging writers, editing and publishing new writing and with every new book setting a higher standard for writing from Singapore. What remains missing is the marketing savvy and infrastructure required to keep these books in the forefront of bookstores and readers' minds.

One clever strategy is investing in a new book prize.

Applying for arts creation grants or nominating a writer for the Cultural Medallion is a largely closed process, and so fails to excite the imagination of writers and readers in the way a single book prize can.

As the organisers of the Man Booker Prize have found, the announcement of a number of entries, a longlist and a shortlist whet people's desire to know more about the submitted books and to read the ones that make it to the final round. One needs just to look at bestseller lists to notice that winners of the Man Booker Prize or the Costa Book Awards or even the Baileys Women's Prize for Fiction are almost guaranteed to top sales charts here.

Last year, the Singapore Literature Prize was heavily promoted - shortlisted books were arrayed in stores and libraries with promotional stickers and posters, authors appeared at bookstores and art galleries to talk about their work - yet none of the shortlisted or even winning works have yet appeared on The Straits Times bestseller list, which takes in sales reports of English titles from major bookstores here.

The problem might be reader confidence in the quality of Singapore writing. At the same time, writers and publishers here all agree that the existing award structure has failed to promote interest in Singapore writing at home or overseas.

First, the Singapore Literature Prize is given out only every two years. Second, it has been at the same $10,000 value since 2004, in spite of inflation and thereby, inflated expectations.

In contrast, the Man Booker Prize for a novel in English offers £50,000 (S$102,400) to the top book, the Baileys Women's Prize for Fiction (for the best in women's writing all over the world) has a cheque of £30,000 for the winner.

Next, the Singapore Literature Prize often goes to established writers in a local pool that excludes Singapore-born writers who have emigrated, such as critically acknowledged Australian poet Boey Kim Cheng (Between Stations, 2009) as well as American chick-lit bestseller Kevin Kwan (Crazy Rich Asians, 2013).

In contrast, the Epigram Books Fiction Prize is very attractive. It is being pitched as an annual award and bigger in value than the Singapore Literature Prize. It is open to submissions from Singaporeans, permanent residents and the Singapore-born. This widens the field and heightens the glory that would go to the future winner.

The Epigram Books Fiction Prize is also deliberately engineered to encourage novelists. Long-form narratives from Singapore are few and far between, with writers preferring the compact forms of poetry or short stories, which many say take less time to craft.

As for the quality of the winning work, whether it will be chosen for commercial appeal or literary value is up to the judging panel led by Mr Wee.

It is his prize, his money and therefore nobody else's to comment on or criticise.

The fact is that the new fiction prize appears to be doing all a national prize should do: Encourage new writing and a still-nascent genre of writing, and confer fame and recognition on the winner.

So this is a prize that should stir the competitive instincts of the National Arts Council and other official bodies invested in developing the literary arts here. Why is it that with so many official resources to tap, the current national literary awards are unable to meet the expectations of writers here? That is the $20,000 question at least one publisher has asked.

akshitan@sph.com.sg