Commentary: Why it makes economic sense to invest in well-being of women and children in Asia

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

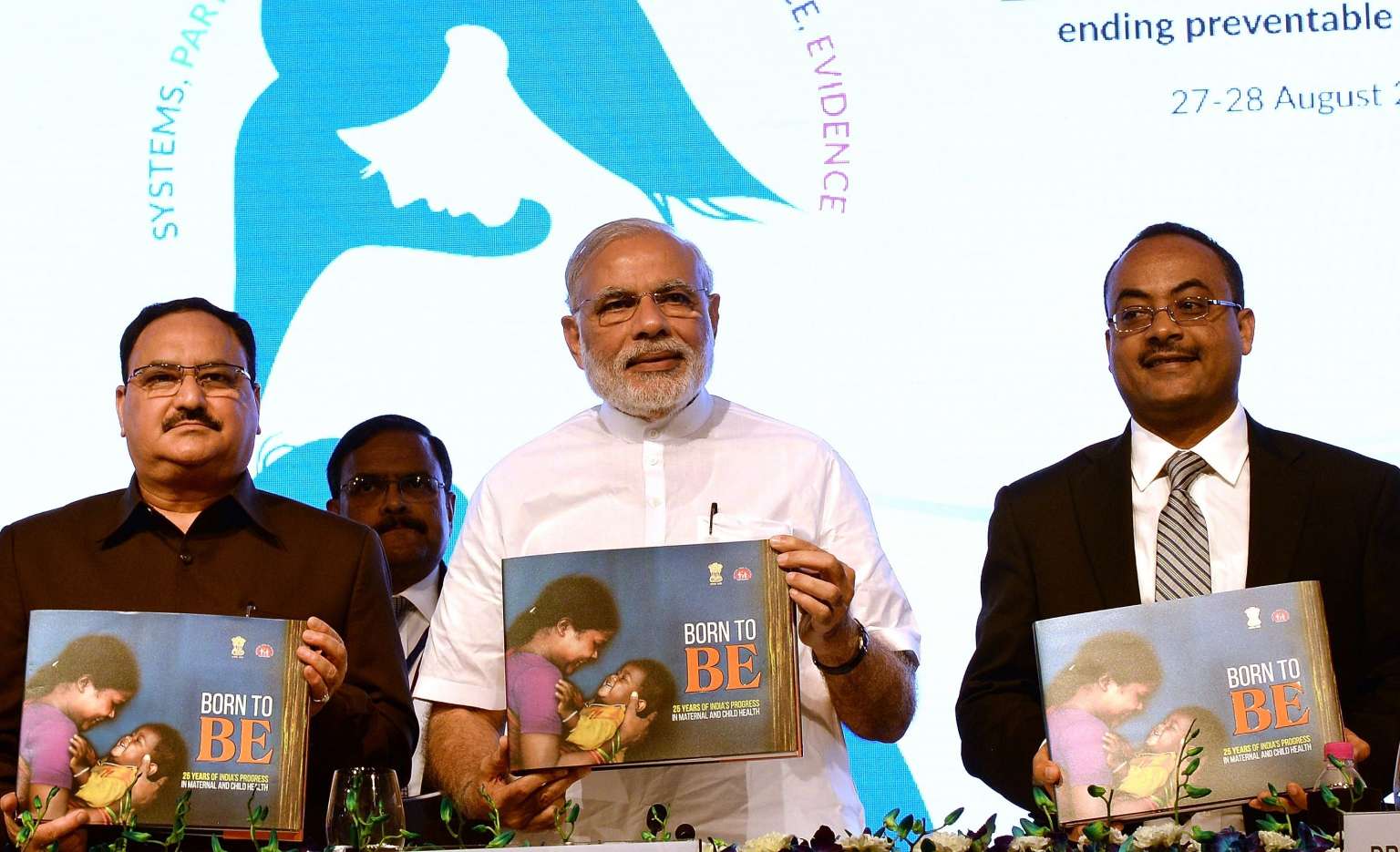

India Prime Minister Narendra Modi (centre), Indian Health Minsiter Jagat Prakash Nadda (left) and Ethopian Health Minister Kesetebirhan Admasu posing for a photograph during the "Call To Action Summit" in New Delhi on Aug 27, 2015. The summit is a global meet aimed at ending preventable child and maternal deaths.

PHOTO: AF

By C.K. Mishra and Amina J. Mohammed

Follow topic:

We often think of money spent on hospitals or schools as "costs": the government raises money via taxes, and spends it on things such as new hospitals or hiring teachers. Money is raised, and money is spent. End of story. But rather than "costs", it would be more appropriate to consider such spending as "investments" because it accrues long-term rights and dividends to the economy and to society. According to recent research, some of the best returns accrue from investments in the health and well-being of women, children and young people.

Take the example of childbirth. According to a study published in the Lancet, money spent on providing good antenatal healthcare leads to a "triple" return on investment to the economy and the society at large. Meanwhile, investments aimed at improving nutrition have, on average, a benefit-cost ratio of 16:1.

When preventable complications arise during labour, the woman and her child may be left permanently sick or disabled. This will impose huge long-term costs on them and their families, and on the government too.

Likewise, investing in the diet of children so that they receive the calories they need for growth ensures they grow up being healthier and more productive, thus preventing avoidable deaths and healthcare costs to society and government.

Studies show that eliminating under-nutrition in Asia would improve early development and education , and increase the GDP of Asian countries, on average, by a staggering 11 per cent. Meanwhile, promoting breast-feeding in the first two years of a child's life could avert almost 12 per cent of deaths in children aged under five, prevent malnourishmentand ensure a good start for every child.

Last month, health officials across Asia attended the Call To Action Summit in New Delhi, which aimed to take stock of progress, share best practices, and forge alliances for ending preventable child and maternal deaths.

Many Asian countries, including India, have also enthusiastically supported UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon's Every Woman Every Child initiative to tackle the health problems faced by women, children and adolescents. This is a prominent agenda for the region and the world, and especially for the future generations who will inherit this planet.

Progress, however, has been uneven. Direct investments in the health sector are only half the story: investments to ensure girls complete secondary school yield an average return of around 10 per cent in low- and middle-income countries. These returns include the health and social benefits of informed pregnancies and reduced fertility rates - because girls who finish secondary school tend to marry, and have children, later than girls who leave school early.

Interventions to prevent forced, child and early marriage -- something Governments must do from a legal and moral standpoint -- also bring tremendous benefits -- not only to the children in question, but also the wider society. Girls that are married too soon, for example, tend to have lower levels of education and reduced economic earning potential. High rates of child marriages are also linked to lower use of family planning, which hinders child spacing and results in more unintended pregnancies.

Investments in the environment also generate big returns. According to recent studies, every dollar invested in improving water, sanitation and hygiene, accrues US$4 to the society at large. Meanwhile, tackling indoor air pollution improves health-related productivity, on average, from 17 to 62 per cent in towns and cities and 6 to 15 per cent in rural areas.

Most Asian nations have much to be proud of when it comes to tackling poverty and improving the health of its citizens. In India, for example, over the past 25 years, maternal mortality rates have fallen by two-thirds, while child mortality rates have halved. More girls and women than ever before can access family planning and reproductive health services.

This is good news, but more data collection and analysis is needed to aid in the decision-making process.The realisation of the Sustainable Development Goals will require considerable resources, with serious implications on existing business models. The world must rethink how the international community delivers value in this new development era. We have to build institutions and develop partnerships that allow for different stakeholders to come together -- and work together -- to ensure that essential interventions get delivered to those who need them most, no matter who they are or where they live.

Money spent to ensure and improve the well-being of women and children shouldn't be viewed as a cost: it's the best investment we can make for the future of our nations.

stopinion@sph.com.sg

Chandra Kishore Mishra is the Additional Secretary in the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, India, and co-chair of The Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health, and Amina J. Mohammed is the United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon's Special Adviser on Post-2015 Development Planning.