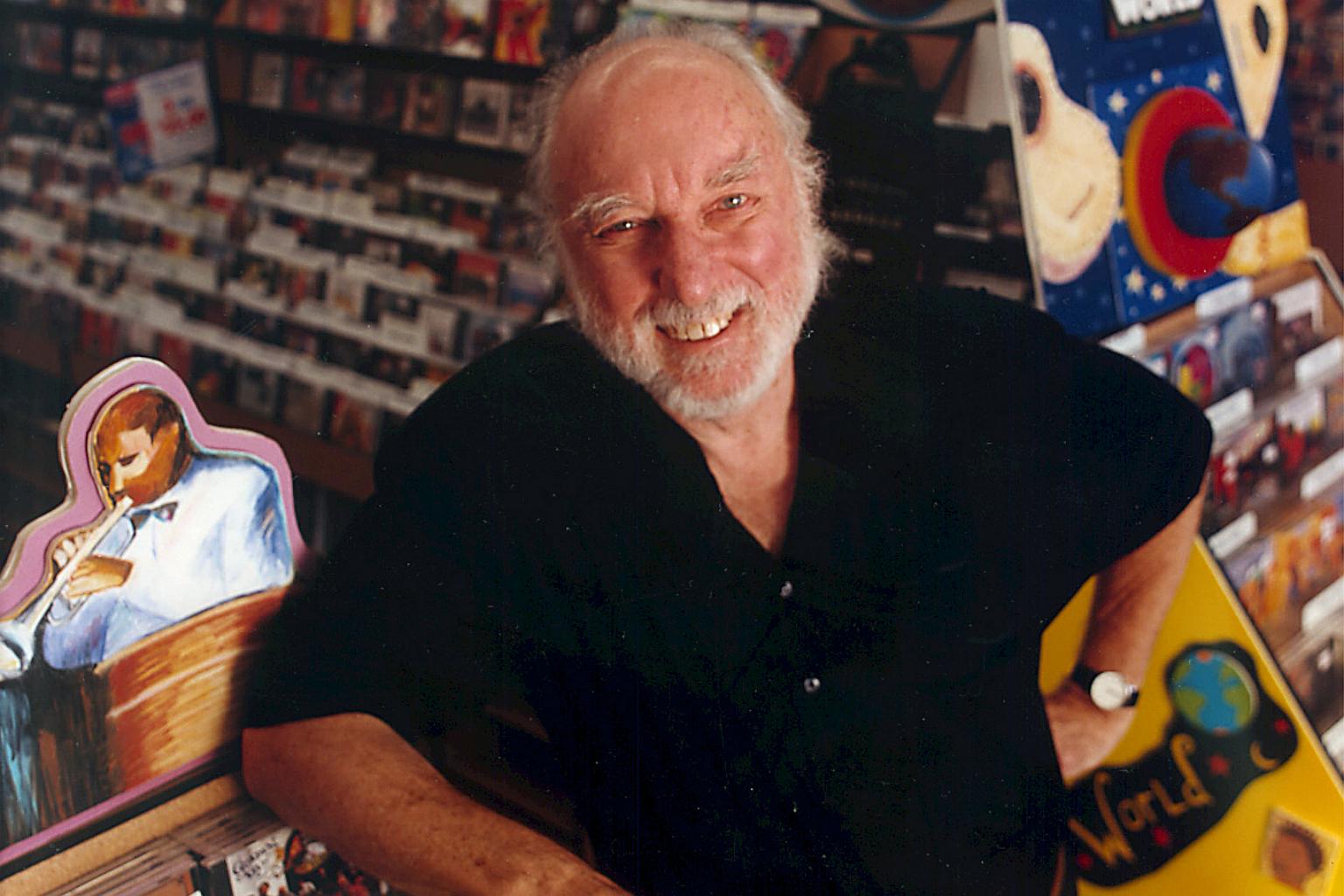

Russ Solomon, founder of Tower Records, dies while watching Oscars and drinking whiskey

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Russ Solomon died, apparently of a heart attack, on March 4, at his home in Sacramento, California.

PHOTO: TOWER RECORDS

NEW YORK (NYTimes) - The founder of iconic record store chain Tower Records, Russ Solomon, died of an apparent heart attack while watching the Academy Awards ceremony on television with a drink in his hand. He was 92.

His son Michael confirmed the death.

In an interview with The Sacramento Bee newspaper, Michael said of his father: "Ironically, he was giving his opinion of what someone was wearing that he thought was ugly, then asked (his wife) Patti to refill his whiskey."

When she returned, he had died.

Solomon, who pioneered the superstore hangout for music lovers by founding Tower Records and expanded it worldwide before Internet pirates and crushing debts rendered the chain obsolete and bankrupt, died on Sunday night (March 4) at his home in Sacramento, California.

A high-school dropout who sold used jukebox records at 16 in his father's drugstore in Sacramento, Solomon was the driving force behind a sprawling enterprise that began with one store in that city in 1960 and grew into a dominant competitor in music retailing, with nearly 200 stores in 15 countries. Sales of recorded music, videos and books eventually topped US$1 billion a year.

With marketing instincts that even rivals and critics called ingenious, Solomon built megastores, some bigger than football fields, and stocked them with as many as 125,000 titles, virtually all of the popular and classical recordings on the market.

Yet, many patrons said there was a clublike intimacy about the stores, where, as Bruce Springsteen once put it, "everyone is your friend for 20 minutes". Open all year from 9am to midnight, staffed by hip sales staff who could answer almost any question about recordings, the stores became the haunts of music aficionados scouring endless racks for rock, heavy metal, jazz, blues, standards, classicals, country-westerns and myriad other offerings. Sometimes, popular bands and singers performed in the stores.

Springsteen, Bette Midler, Lou Reed and Michael Jackson were regular patrons. So was David Chiu, a Brooklyn journalist.

"When you walked into the Tower Records store in New York City's Greenwich Village neighbourhood back in the day, you just didn't go in there to buy an album and then rush off to leave," he wrote in Cuepoint, an online publication, in 2016.

"To me, going into Tower was like visiting the Metropolitan Museum of Art or attending a baseball game - it required a certain investment of time."

Solomon told Billboard magazine in 2015: "Our favourite regular was Elton John. He probably was the best customer we ever had. He was in one of our stores every week, literally, wherever he was - in LA, in Atlanta when he lived in Atlanta, and in New York."

In an interview for this obituary last September, Solomon recalled that he opened the first Tower Records store in what had been his father's drugstore with US$5,000 in borrowed capital. He called it "a neighbourhood business", which he named after the Tower Theatre, a local landmark that was built in 1938 and topped by a neon-bathed, 30m art deco pillar.

He soon opened a second Sacramento outlet. But the business did not take off until 1968, when he opened Tower Records in San Francisco. It was an instant sensation in the heart of the hippie and music scene, capitalising on the 1967 Summer of Love. At 5,000 sq ft, the store was small by later company standards, but it set a formula for the future: wide selections and discounted prices.

"I stole ideas from supermarket merchandising," Solomon recalled. The store, he said, stacked hot-selling items on the floor, to encourage impulse buying and to suggest plentiful supplies, reinforcing the impression that Tower would be well stocked when competitors' supplies had run out. The store also set late-night closing hours.

But the most important innovation, he said, was hiring a staff so well versed in the local music scene that the store could order its own inventory. It was a task that music chains typically assigned to a central office to achieve economies of scale for their outlets. But Solomon found that local judgments were more profitable, and decentralised ordering became a pattern for all his stores.

"We wanted people in the store to run the store - they're your strength," Solomon said. "Central buying is just a bad idea. You can't make decisions on what to do in Phoenix if you're sitting in New York or London."

As business boomed in the 70s and 80s, he established Tower Records outlets in major cities across the United States, many with 20,000 sq ft to 40,000 sq ft of space. The New York flagship, in Greenwich Village, opened in 1983.

Tower began opening stores abroad in the 1980s, starting in Japan and spreading in Asia, Europe and Latin America. In the 1990s, it became the nation's largest privately held music retailer, with nearly 200 stores in the United States and 14 other countries.

But it never went public. "That was the dumbest thing I ever did," Solomon conceded. Selling stock might have paid for further expansion. Instead, he borrowed to finance more stores, and his debt swelled to US$300 million. In 1999, Tower sales topped US$1 billion, but its financial tailspin had already begun. The company lost US$10 million in 2000 and US$90 million in 2001.

Solomon sold and closed stores and converted others to franchises. At the same time, the music business went into a slump. Tower declared bankruptcy in 2004, and in 2006, it was forced to liquidate and close.

Solomon acknowledged that he had underestimated the Internet's threat to store retailing. Pirates downloaded music without paying for it, and paying customers turned to online vendors and price-cutters such as Walmart and Best Buy. The owner blamed himself.

"I was overextended," Solomon said. "I was swamped by the debt."

Russell Malcolm Solomon was born on Sept 22, 1925, in San Francisco to Clayton Solomon and Annette Sockolov. The boy and his sister, Shirley, grew up mostly in Sacramento, the state capital, where their father established his business, Tower Cut Rate Drugs, in the late 1930s.

Russell, an indifferent student, was expelled for repeated truancy from C.K. McClatchy High School at 16 and went to work for his father. He served stateside in the Army Air Forces from 1944 to 1946.

In 1946, he married Doris Epstein, whom he later divorced. In 2010, he married Patricia Drosins, who survives him. Besides his son Michael, he is also survived by another son, David, four grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.