MIGRANT CRISIS SPECIAL

Trapped in Indonesia refugee camp for years after failing to reach Australia

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

Follow topic:

MEDAN, North Sumatra - Father of two Abdul Rahim kept a close eye on the weather when he was planning a brighter future for his young family and knew he had only a short time to act.

The period from February till May offers the best hope for Myanmar's Rohingya, one of the world's most persecuted minorities, to head to sea and begin their dangerous journey to a new beginning, often in Malaysia or Australia.

"There is no strong wind, no heavy rain. The sea is calm," said 34-year-old Mr Rahim, who reached Malaysia more than a decade ago but has hit a dead end in Indonesia after he and his family failed to make it by boat to Australia three years ago.

"The most dangerous time is in the months of seven, eight and nine," Mr Abdul added, referring to July, August and September.

He saved RM23,000 (S$7,552) to pay a people smuggling agent to get him and his family to Australia.

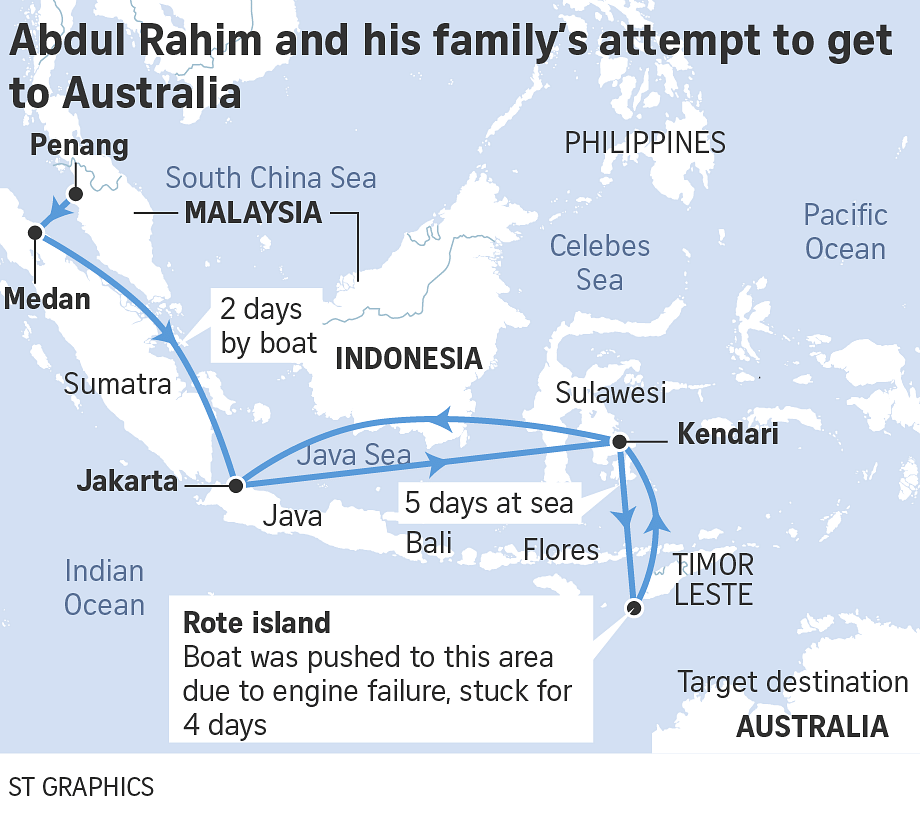

In May 2012, Mr Abdul, his Indonesian wife and their two young daughters, then two years old and four months old, crossed from Penang in Malaysia to Medan in Indonesia's North Sumatra province.

From Medan, the family travelled for two days by bus to Jakarta and took a flight to Kendari, South Sulawesi, the starting point of their treacherous trip to Australia.

After five days at sea, their boat reached Australian waters, but the engine failed as they struggled to make their way closer to Christmas island. The Rohingya desperately waved to the crew of a passing Australian Navy vessel, which Mr Abdul said did not respond.

The boat was then pushed back by waves and currents towards Indonesia and the 157 on board were rescued by local fishermen who took them to an unnamed, small island (which locals call Toyam island) very near Rote island. They stayed there for four days before Indonesian Navy came and moved them to Kendari on Sulawesi island, from where they were sent to Jakarta.

Waiting to be relocated to a third country

Mr Abdul and family have lived in Indonesia's Surabaya in East Java province since then and are waiting to be relocated to a third country by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

Of Myanmar's Rohingya population of four million roughly, 2.5 million have fled decades of persecution and repression in the country, where they are effectively stateless under a 1982 Citizenship Law.

Most have found their way to Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, Australia, Bangladesh and Pakistan and another 200,000 are likely to try to flee this year, according to Mr Mohiuddin Mohamad-Yusof, president of the New York-based World Rohingya Organisation (WRO), which promotes the rights of the boat people and helps newly arrived refugees. It gets funding from the Rohingya diaspora.

Today, there are more than 1,000 Rohingya in Indonesia, including 200 in East Nusa Tenggara Timur, 300 in North Sumatra, 300 in Aceh and 200 in Sulawesi. Many arrived in the country in May 2015.

Indonesia's coordinating minister for political, legal and security affairs Luhut Pandjaitan told The Straits Times that Jakarta is keen to help resolve the refugee issue but its resources are not unlimited. The government is open to the possibility of allocating a place or an island for the Rohingya to live temporarily prior to relocation, but says funding should come from Australia.

In Indonesia, the Rohingya are issued a UNHCR card and receive monthly stipends, and are not allowed to work. The right to this stipend is waived once a refugee is married to a local, like Mr Abdul.

Mr Abdul shares grievances with Mr Zokir Ahmad, 30, a rice paddy farmer who left Myanmar five years ago, thinking that any place would be better than home. He wants to train to become a mechanic.

"I am really bored. Day and night I have been waiting to hear a good news that they send me to a third country," said Mr Zokir, who is not married.

When he left his country, he said that he was not sure where to go. "We were heading to the sea. That was all we knew. We aimed for a place where we could live peacefully and work like a normal human being."

He lives in a small motel room with a roommate in Medan, North Sumatra, provided by UNHCR and gets 1.25 million rupiah (S$125) a month as stipend. The money, he said, has to cover his daily meals, soap and detergent, and any unexpected expense such as repairs costs if the fan in his room broke.

Rohingya refugees at the lobby of Pelangi hotel in Medan. UNHCR puts up 102 refugees in 50 of the hotel's 70 rooms. ST PHOTO: WAHYUDI SOERIAATMADJA

For Mr Mohammad Iliyas, who has seven children, the money he receives adds up to six million rupiah a month, or more than twice the minimum wage in Indonesia. Each adult is entitled to 1.25 million rupiah a month and each child 500,000 rupiah a month. The family arrived in Indonesia more than two years ago.

The 42-year-old father married a fellow Rohingya refugee in Malaysia and had their first six children there. The youngest child was born here.

All their children are enrolled in a school near the refugee camp, a motel in Medan whose rooms are rented by UNHCR. For each child, he pays between 50,000 rupiah and 70,000 rupiah a month for the school fees and about 400,000 rupiah for books every six months.

The Indonesian government should give the Rohingya refugees a temporary residency status, said WRO's Mr Mohiuddin. This would allow them to work legally until after Myanmar can complete the transition to a civilian democracy after the recent election results and their rights are restored.

"The best way is to work with the Asean governments to negotiate with Myanmar's democratic government to restore the Rohingyas citizenship rights and repatriate the Rohingya refugees in Asean countries, including Indonesia, back to Myanmar," Mr Mohiuddin said in an e-mail reply to The Straits Times.

"The second option is to resettle them in a third country which can be implemented if UNHCR and the Indonesia government work together for relocation," he added.

Another refugee Mohammad Noor, 27, said refugees from Myanmar have often been overlooked, compared with those from Sudan or Afghanistan, who on average get relocated to a third country after about two years.

Mr Noor has lived in Medan for more than five years - like many other fellow Rohingya refugees - and can't wait until he can work and live a normal life.

"How much longer would we wait here? If they don't want to relocate us to another country, then they should let us be an Indonesian citizen."

"If you stay in any one place more than five years and you never breach a law, you should get naturalised," Mr Noor added.