GEORGE TOWN (Penang) - The old pakcik in a sarong cycled slowly by the madrasah, or Islamic religious school, nodding a brief hello to a young woman cycling past.

Their bicycle wheels threw up sand from the path that runs alongside the wooden houses. It was a typical scene from a typical seaside fishing village in Malaysia, except that this was in George Town in Penang.

Kampung Tanjung Tokong is one of the oldest Malay villages in Penang and its survival is deeply important to the Malay community. It was one of the many traditional fishing villages that lined the shores of the cape of Tanjung Tokong that juts into the Strait of Malacca.

Now, it is under threat, surrounded by luxury developments and a Tesco hypermarket. Penang's rapid development has brought high-rise buildings to its doorstep and developers knocking on villagers' doors.

The village occupies prime waterfront land just minutes from George Town's business district. Yet, it seems a world away.

A few steps into the village, the noise of the city melts away. The paths meander among the houses built in a random fashion that characterises a traditional kampung.

Many are still the traditional wooden houses with a verandah used to grow plants and to dry the washing.

There is strong resistance in the village to redevelopment, with support from heritage conservationists and academics.

People have been living there long before the English trader, Captain Francis Light, landed in 1786 to set up a British settlement. Penang later became a crown colony and part of the Straits Settlements that also included Malacca and Singapore.

Dr Wazir Jahan Karim, an anthropologist, wrote in an article that family histories there go back more than 300 years. The genealogical records of some families date back to before the arrival of the British.

"This is unique to Penang's urban history… Tanjung Tokong is even older than George Town," said Dr Wazir Jahan, who is also a fellow at the Academy of Socio-Economic Research and Analysis, an academic trust on economic justice issues.

But this is little known. The wealth of colonial buildings and Chinese shophouses in George Town give the impression that the British were the first to set foot there.

The scant remembrance of the Malay heritage sometimes rankles. Penang island is one of the few places in Malaysia where the Chinese and the Malays are almost equal in number, and it is the only state in Malaysia with a Chinese chief minister.

There are, however, plans to preserve heritage zones beyond the inner city's old quarter, and that would include Malay areas such as Tanjung Tokong, Balik Pulau and the Penang mainland.

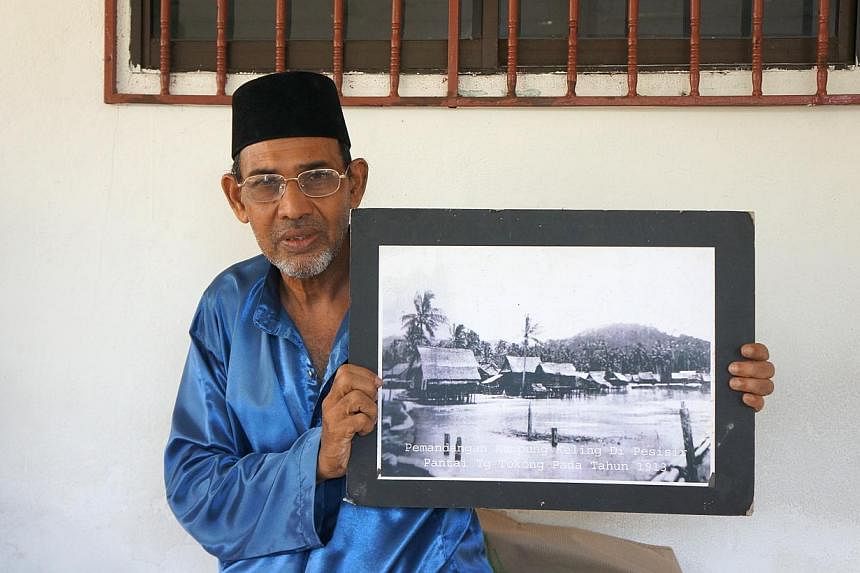

Mr Mohd Salleh Yahaya, 60, who chairs the Tanjung Tokong residents' association, said the state recently called for meetings for the preservation and promotion of heritage beyond George Town.

He was happy that Kampung Tanjung Tokong was included.

He said George Town is known around the world for its heritage "but only now, they are looking at areas beyond the inner city".

"We don't want our heritage to be erased altogether," he said, adding that much of the heritage of the old Malay fishing villages was destroyed due to neglect.

Part of this is because fishing is no longer a viable occupation. Many of the kampung's people have turned to the tourism industry but often occupy the lower strata where incomes are low.

The future of the village could be secured through promoting its heritage and attracting visitors to experience the customs, food and way of life.

The state government has promised to recognise it as a heritage site to be managed by the community.

The problem is that the land was given over to a federal government corporation, Urban Development Authority Holdings, in 1972. The decision on whether to preserve Kampung Tanjung Tokong rests in its hands. And so far, it does not seem to have any plans to do so.

Parts of the land have been cleared but much of the village still remains.

"I don't really know the status now. No one has told us anything. We just hear whispers," said a housewife, who wanted to be known by her nickname Jat.

Her family has lived there for six generations, and her father was the imam of the village mosque.

Dr Wazir Jahan said there is still a vibrant community there. It is famed for its traditional markets, Malay culture and food such as mee kuah udang (prawn gravy noodles).

"Our community hall called Kelab Setia Tanjung Tokong, built in 1911, was torn down without notice some years ago," said Mr Salleh. He pointed to the madrasah, which is about 90 years old.

The madrasah Al-Taqwa, said to have been built in 1925, comprises several small buildings within a shady compound.

The main mosque, Masjid Tuan Guru, has, however, been rebuilt into a sleek modern building, and sits metres from a large Chinese temple. The locals say the Chinese have lived there for generations.

"We accept it as part of the heritage of this area," Mr Salleh said.

The village, it is said, was named after the cluster of rocks around the cape; "tokong" is an old Malay word for rocks. Today, though, the word generally refers to "temple".

Most of its houses are located inland but those near the beach bore the brunt of the Boxing Day tsunami that hit the northern part of Peninsular Malaysia in 2004.

Villagers still talk about it.

Madam Jat remembered water entering their houses, even though they were far from the beach.

As she recounted what happened, a green van stopped outside her house, offering fresh food, vegetables and sundry items from a local shop.

Her daughter bought some vegetables for a family gathering that day.

But while such roving markets are still around, life is a bit different now. Madam Jat said many community-based activities such as weddings now tend to be confined to just family and friends. "Gotong royong", or communal work, is also hardly carried out today.

That is why Dr Wazir Jahan said it was important to maintain housing which is essentially "Malay", to give the people a sense of cultural belonging and history.

"Village life has always shaped a Malay community… and is conducive to Malay rites of passage - weddings, births and deaths which are still community-managed and not farmed out to caterers in rented premises in George Town," she wrote.

Mr Salleh said upgrading the remaining 240 houses would help the locals benefit from the tourism boom that has brought much wealth to this island. The villagers have ideas about showcasing Malay heritage and culture there, from food to leisure activities.

This is one way for Penang's oldest village to thrive within a city.

Mr Salleh said they were not against development but wanted development to take into account their community needs.

"Development should not exclude heritage," he said. "There's commercial value in heritage."