Cultural Revolution

50 years on, Cultural Revolution still off limits in films, books in China

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

Jason Ou

Follow topic:

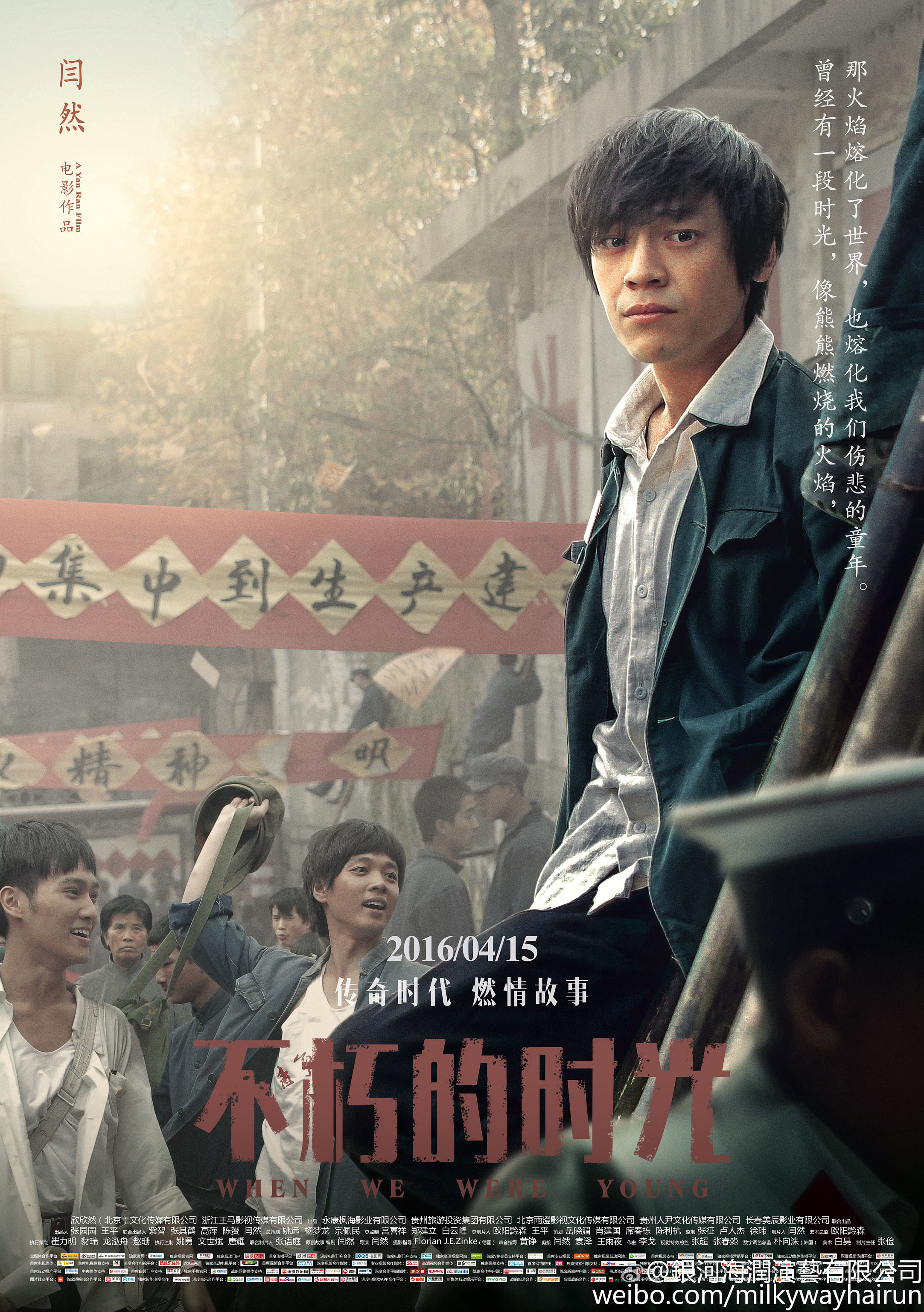

It took state censors two years before they gave the green light to director Yan Ran's latest film, which touches on the Cultural Revolution. But less than two weeks after the film hit the big screen on April 15, it was withdrawn from most of China's cinemas for a lack of support from their operators.

The low-budget When We Were Young is one of only a few unbanned movies that depict the tumultuous decade (1966-1976) under Mao Zedong.

The low-budget When We Were Young is one of only a few unbanned movies that depict the tumultuous decade (1966-1976) under Mao Zedong.

"I sweated it out every time I was questioned by related departments or when I tried to express myself," Mr Yan, 42, told Chinese media in April, saying the two-year-long inspection was "excessively long".

A poster of Yan Ran's film When We Were Young.

PHOTO: SINA WEIBO

"But certainly, China's movie censorship is not as demonic as people think. The approval for this film shows we've made a great step forward. I'm very satisfied," he added.

China has kept a tight grip on films and publications about the Cultural Revolution, fearing that an in-depth discussion of the political upheaval that claimed millions of lives would erode the legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party, analysts said.

While the authorities have never revealed any censorship guidelines, they have banned films and books that could stoke criticism of the government by portraying the excesses of the turmoil in a candid manner.

Many of the banned films, such as The Blue Kite (1993) and To Live (1994), were screened overseas and won international awards.

China has kept a tight grip on films and publications about the Cultural Revolution, fearing that an in-depth discussion of the political upheaval that claimed millions of lives would erode the legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party, analysts said.

While the authorities have never revealed any censorship guidelines, they have banned films and books that could stoke criticism of the government by portraying the excesses of the turmoil in a candid manner.

Many of the banned films, such as The Blue Kite (1993) and To Live (1994), were screened overseas and won international awards.

Hollywood has largely kept its hands off the theme. But the political movement has at times appeared briefly in some foreign-produced movies, such as the award-winning The Last Emperor - an epic biographical film about the life of Pu Yi.

"The Cultural Revolution is still off limits, for the most part. The things you can say about it are still very limited," Mr Zhang Yimou, an internationally renowned Chinese director, told online magazine ChinaFile in 2015.

His last film, Coming Home, escaped the censors in 2014 despite its mention of the Cultural Revolution. But unlike his earlier masterpiece, To Live, Coming Home has a lack of criticism and a reflection on history and politics, critics said.

"The Cultural Revolution is still off limits, for the most part. The things you can say about it are still very limited," Mr Zhang Yimou, an internationally renowned Chinese director, told online magazine ChinaFile in 2015.

His last film, Coming Home, escaped the censors in 2014 despite its mention of the Cultural Revolution. But unlike his earlier masterpiece, To Live, Coming Home has a lack of criticism and a reflection on history and politics, critics said.

A screengrab of Zhang Yimou's film To Live.

PHOTO: SINA WEIBO

Like Coming Home, Mr Yan's film is mostly set in the post-Cultural Revolution era. It is a story about friendship between six adolescents in the early 1980s, with all experiencing the political turbulence in childhood.

The plot and structure of the film is "significantly different" from his first draft, but he has strived to preserve in it "the attitude to bravely recall history", Mr Yan said.

Despite his efforts, China's cinema chains reportedly snubbed the film that features no celebrities but a heavy subject. They gave it limited screenings that took in only 700,000 yuan (S$147,000) in two weeks.

Before Chinese filmmakers took up theatre as a platform to reflect on the Cultural Revolution, writers in the late 1970s began to create Scar literature - a genre dedicated to revealing the painful experiences during the upheaval.

Many works of the kind, mostly short stories, popped up during the Beijing Spring, a period between 1978 and 1979 when the new government under Deng Xiaoping created a relaxed political atmosphere.

But the works, which often painted the Cultural Revolution in a melancholic light, drew flak from critics and gradually disappeared in the 1980s as the government tightened its grip again.

"In these works, the brutality of the Cultural Revolution was depicted and rejected for the first time," said Dr Wang Youqin, a Chinese language lecturer at Chicago University.

"However, Scar literature just touched the surface, and it was not allowed to dig deeper."

In the same way as how they treat movies from the 1990s, official censors give the nod only to publications that toe the line. But this "line" appears even more ambiguous than that for movies.

While some movies are banned, the literary works from which they are adapted are allowed to be published, such as Mr Yu Hua's novel To Live.

Sometimes the censors flip-flop after a book comes onto the market, and scramble to recall the publication.

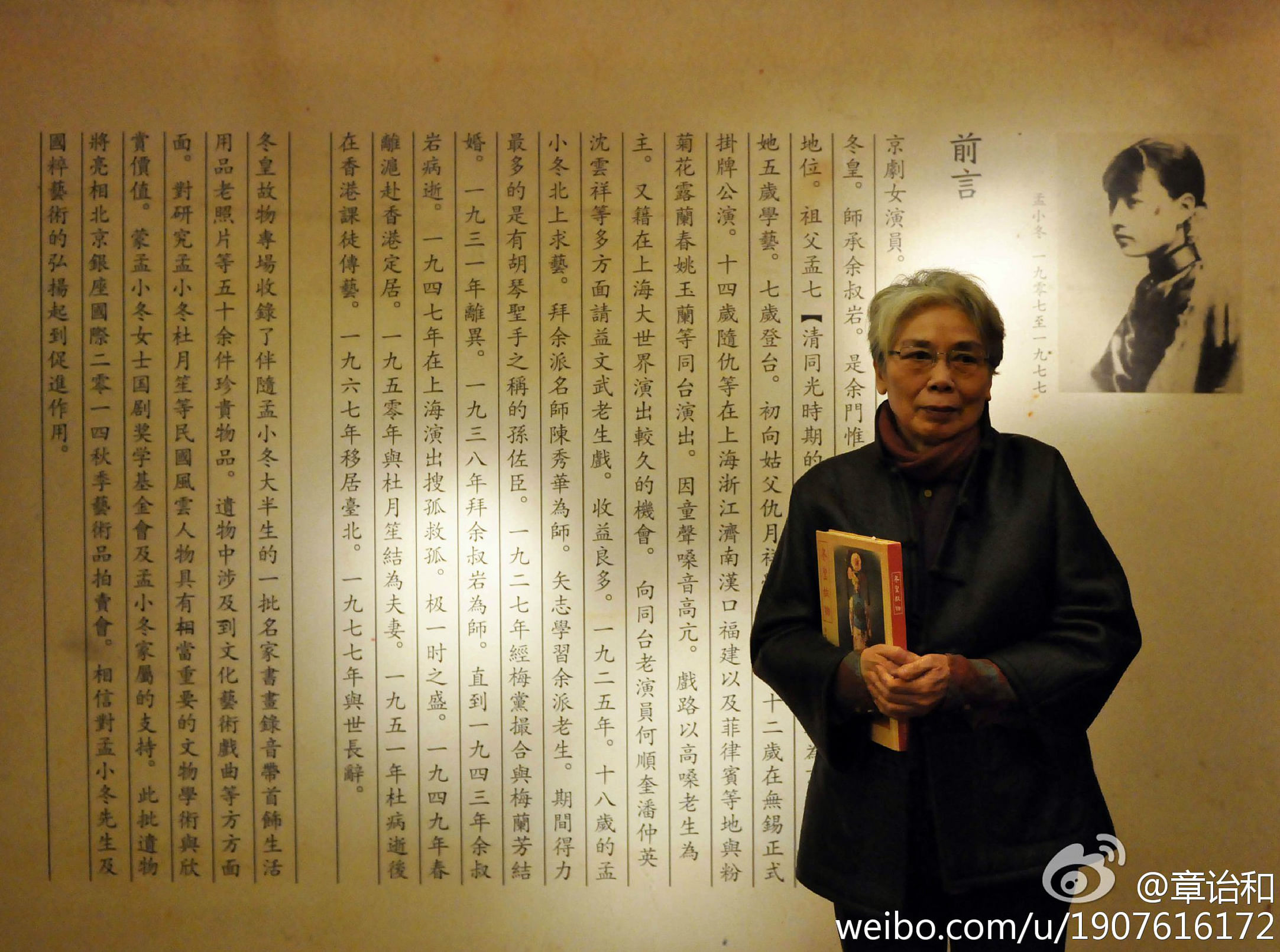

A case in point is Ms Zhang Yihe's The Past is Not Like Smoke, which became an instant best-seller after its release in 2004 but was banned soon afterwards. Still, some estimates claim more than one million pirated copies continued to circulate in China after the ban.

"The authorities can ban a book under China's current system, but the question is how you do it? It should go through an open, fair, and independent legal procedure.

But none of this exists," Ms Zhang, 73, told Voice of America in an interview, after two more of her books were banned in 2005 and 2006.

The book banned in 2004 is a memoir of her late father Zhang Bojun - labelled "China's number one rightist" - and his associates who were purged in the Anti-Rightist Campaign in 1957 and the Cultural Revolution.

The plot and structure of the film is "significantly different" from his first draft, but he has strived to preserve in it "the attitude to bravely recall history", Mr Yan said.

Despite his efforts, China's cinema chains reportedly snubbed the film that features no celebrities but a heavy subject. They gave it limited screenings that took in only 700,000 yuan (S$147,000) in two weeks.

Before Chinese filmmakers took up theatre as a platform to reflect on the Cultural Revolution, writers in the late 1970s began to create Scar literature - a genre dedicated to revealing the painful experiences during the upheaval.

Many works of the kind, mostly short stories, popped up during the Beijing Spring, a period between 1978 and 1979 when the new government under Deng Xiaoping created a relaxed political atmosphere.

But the works, which often painted the Cultural Revolution in a melancholic light, drew flak from critics and gradually disappeared in the 1980s as the government tightened its grip again.

"In these works, the brutality of the Cultural Revolution was depicted and rejected for the first time," said Dr Wang Youqin, a Chinese language lecturer at Chicago University.

"However, Scar literature just touched the surface, and it was not allowed to dig deeper."

In the same way as how they treat movies from the 1990s, official censors give the nod only to publications that toe the line. But this "line" appears even more ambiguous than that for movies.

While some movies are banned, the literary works from which they are adapted are allowed to be published, such as Mr Yu Hua's novel To Live.

Sometimes the censors flip-flop after a book comes onto the market, and scramble to recall the publication.

A case in point is Ms Zhang Yihe's The Past is Not Like Smoke, which became an instant best-seller after its release in 2004 but was banned soon afterwards. Still, some estimates claim more than one million pirated copies continued to circulate in China after the ban.

"The authorities can ban a book under China's current system, but the question is how you do it? It should go through an open, fair, and independent legal procedure.

But none of this exists," Ms Zhang, 73, told Voice of America in an interview, after two more of her books were banned in 2005 and 2006.

The book banned in 2004 is a memoir of her late father Zhang Bojun - labelled "China's number one rightist" - and his associates who were purged in the Anti-Rightist Campaign in 1957 and the Cultural Revolution.

Zhang Yihe, daughter of "China's number one rightist" Zhang Bojun.

PHOTO: SINA WEIBO

If the censors are occasionally uncoordinated in handling Chinese books, their attitude towards foreign publications on the subject is clearly dismissive.

China did not translate or sell any English accounts of the Cultural Revolution.

Some well-received works published in the West, including Ms Jili Jiang's Red Scarf Girl: A Memoir of the Cultural Revolution (1998) and Mr Da Chen's China's Son: Growing up in the Cultural Revolution (2004), remain largely unknown in China.

These works written in English by Chinese migrants mostly express the authors' disillusionment with the Cultural Revolution and communist ideals.

"When I asked my child about the Cultural Revolution, she said she didn't know. In fact, many young people have no clue," Mr Feng Xiaogang, 58, an acclaimed Chinese director, said in a panel discussion about the Chinese film industry in 2013.

"If you don't let them know the atrocities committed by the Red Guards, people may relish in smashing windows with stones whenever another riot takes place," he added.

These works written in English by Chinese migrants mostly express the authors' disillusionment with the Cultural Revolution and communist ideals.

"When I asked my child about the Cultural Revolution, she said she didn't know. In fact, many young people have no clue," Mr Feng Xiaogang, 58, an acclaimed Chinese director, said in a panel discussion about the Chinese film industry in 2013.

"If you don't let them know the atrocities committed by the Red Guards, people may relish in smashing windows with stones whenever another riot takes place," he added.