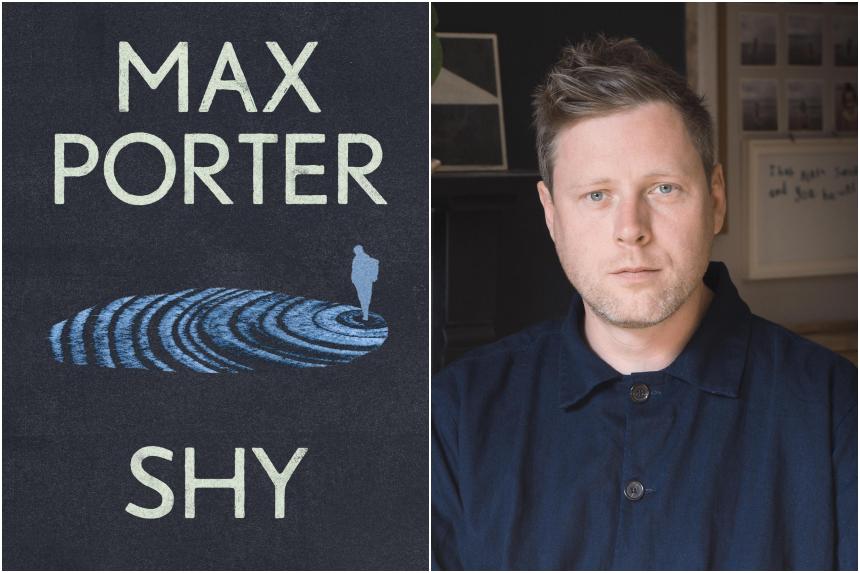

Shy

By Max Porter

Prose poetry/Faber/Hardcover/122 pages/$22.11/Amazon SG (amzn.to/3ELT1Vh)

4 out of 5

This slim, strange, sad book spends a few hours in the head of Shy, a troubled teenager who is escaping Last Chance, an old mansion in the English countryside that might be haunted, but has since been transformed into a boarding school for “very disturbed young men”.

The year is 1995. Shy’s rucksack is full of ancient flints and he is headed for the pond. There, he expects, the flints will weigh him down.

Max Porter, a British bookseller and editor, shot to acclaim with his Dylan Thomas Prize-winning debut Grief Is The Thing With Feathers (2015), in which a bereaved family is visited by a crow.

He made the Man Booker Prize longlist with his sophomore work Lanny (2019), about the disappearance of a young boy in a rural village.

In Shy, his fourth book, Porter continues his freewheeling experiments with form, effortlessly melding prose and poetry in a receptacle that is not quite a novella but allows him to do kaleidoscopic work.

The writing flickers through myriad fonts and formats: colloquial banter, the jargon of social work and psychiatry sessions, jungle and drum ’n’ bass music and voiceovers.

The last of these stems from Last Chance and its residents being filmed, not entirely consensually, for a television documentary, which the staff hope will save it from being converted into luxury flats.

This is strung together with a sinuous lyricism.

Here, for instance, is the pond: “Deceptive, inky-smooth, silent, at ease with its unknown weight.”

The night is a “shattered flicker-drag of these sense-jumbled memories”; Shy thinks he “might topple off this night-edge and scurry back to bed”.

Through all this runs his fractured inner monologue, skittering through time, at times darkly funny, often terribly bleak.

Porter does not sugar-coat: This is a depressed boy prone to misbehaviour and violence, who has “sprayed, snorted, smoked, sworn, stolen, cut, punched, run, jumped” and once stabbed his stepfather in the finger.

He cannot seem to stop hurting the people he loves. Yet, he also contains multitudes and his voice, Porter maintains, deserves to be heard.

Early on, Shy stops on the edge of the lawn and notes it is where “Jamie kicked Nick Fulshaw’s head in last term and the police kept asking why nobody saw him lying there bleeding and everyone said again and again Because of the ha-ha”.

A ha-ha is a garden feature of French origin in which a sunken ditch prevents access without obstructing the view in the way a raised wall might.

In the context of Shy’s recollection, this makes for both a very funny joke, for those erudite enough to know what a ha-ha is, and a discomfiting epiphany about the casual, overlooked brutality of Shy’s underprivileged world, which most would prefer not to see, or contemplate only through the lens of pity or judgment.

In the course of this story, Shy climbs out of his window – out of his box, so to speak – and into the liminal space of Porter’s text.

He is “Caught between times. In the fold. Escaping”.

And escape he does, for a little while, as the book pries open its folds for a glimpse of hope.

If you like this, read: catskull by Myle Yan Tay (Ethos Books, 2023, $24, ethosbooks.com.sg), another experimental novel about troubled youth. Ram, a Singaporean junior college student who is struggling with school, attempts to become a vigilante after intervening in his best friend’s abuse at her father’s hands.