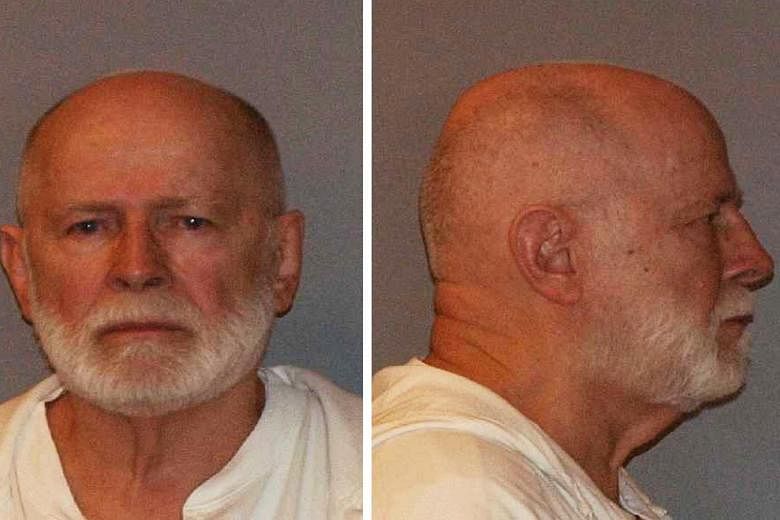

NEW YORK (NYTIMES) - James "Whitey" Bulger, the South Boston mobster and FBI informer who was captured after 16 years on the run and finally brought to justice in 2013 for a murderous reign of terror that inspired books, films and a saga of Irish-American brotherhood and brutality, was found beaten to death on Tuesday (Oct 30) in a West Virginia prison. He was 89.

Two Federal Bureau of Prisons employees said Bulger was beaten unrecognisable by inmates shortly after he arrived.

He had been moved from prison to prison in recent years and was incarcerated in Florida before being transferred to Hazelton federal penitentiary, which has been rife with violence.

A law enforcement official who oversees organised crime cases said he was told by a federal law enforcement official that a mob figure was believed to be responsible for the killing.

Bulger was serving two life sentences for 11 murders.

To the families of those he executed gangland-style and to a neighbourhood held in thrall long after he vanished in 1994, Bulger's arrest in Santa Monica, California, in 2011 and his conviction of gruesome crimes brought a final reckoning of sorts, and an end to the career of one of America's most notorious underworld figures.

In an all-but-lost era in South Boston, Bulger dominated the rackets and folklore in that Irish-American working-class enclave.

Tales of his exploits were learned from childhood there: how he shot men between the eyes, stabbed rivals in the heart with ice picks, strangled women who might betray him and buried victims in secret graveyards after yanking their teeth to thwart identification.

Enriching the Bulger legend, his brother, William, became president of the Massachusetts state Senate and president of the University of Massachusetts. Mr William Bulger always denied firsthand knowledge of his brother's crimes and whereabouts, but said he loved him and could never give him up to the law.

For years before details of Whitey Bulger's criminal history became known through trials, books, newspapers and congressional hearings, popular myths in South Boston portrayed him as an Irish Robin Hood, giving out turkeys on Thanksgiving and protecting his own from the hated police and outsiders.

His code of the streets was touted: Never sell angel dust to children or heroin in the neighbourhood, trust only the Irish, never lie to a friend or partner, and above all never squeal to the authorities. He was an inspiration for Jack Nicholson's mob boss in Martin Scorsese's 2006 film The Departed set in Boston.

But such romantic notions were shattered by disclosures that for some 15 years he had been a federal informer and that the authorities had turned a blind eye to his crimes in exchange for his snitching on the Mafia.

Beyond corrupting agents with bribes, the government said, the arrangement helped him conceal 19 murders, learn the identities of witnesses who later turned up dead, and send an innocent man to prison for a killing that Bulger had committed. It also led to a re-evaluation of rules for dealing with informers.

In December 1994, after decades of extortion, bookmaking, loan-sharking, gambling, truck-hijacking and drug dealing - much of it carried out as the authorities looked the other way - Bulger vanished just as federal officials were about to unseal an indictment and arrest him on racketeering charges.

It was later learned that he had been tipped off by the agent who had been his undercover handler for years.

Bulger and his companion, Catherine Greig, who joined him after he fled, were extraordinarily elusive, despite international searches.

Sightings were reported in Europe, Canada, Mexico and elsewhere in the United States, but no traces were found. For a decade, Bulger was on the FBI's Most Wanted list.

A US$2 million (S$2.7 million) reward was offered for his capture, the largest ever for a domestic fugitive.

After plastic surgery to change their appearances, Bulger and Greig settled in Santa Monica, California, in a small apartment a few blocks from the Pacific, in 1996.

They called themselves Charlie and Carol Gasko and lived reclusively, paying their US$1,145 monthly rent in cash. He spent his days watching television. She took walks, went to a beauty parlour and - being a former dental technician - had her teeth cleaned monthly. They took occasional trips, but mostly stayed home.

Embarrassed by its dealings with Bulger as an informer and frustrated by his invisibility, the FBI in 2011 began a national advertising campaign that focused not on him but on Greig's idiosyncrasies.

Her beauty parlor and teeth-cleaning visits were featured in 350 public service announcements in 14 cities on daytime television shows favoured by older women. They noted that the reward for her had doubled to US$100,000.

Acting on a tip, agents closed in and arrested the couple on June 22. They offered no resistance.

The white-blond Bulger hair had been dyed black and was receding. He was 81 and had a paunch. But the angular narrow face, the jutting chin and the clever eyes behind sunglasses were unmistakable.

"I never thought I'd see this day," Patricia Donahue, whose husband Michael Donohue was killed in a 1982 shooting attributed to Bulger, said after the fugitives were captured. "I have satisfaction and despair, because it brings back so many old memories. But satisfaction that they have him."

After their capture, Bulger and Greig were returned to Boston to face trials.

Greig was charged with harbouring a fugitive and as part of a 2012 plea agreement was sentenced to eight years in prison and a US$150,000 fine. She was later sentenced to 21 more months in prison for refusing, even with a grant of immunity, to testify before a grand jury investigating whether other people had helped Bulger while he was a fugitive.

Bulger was charged with complicity in 19 murders, racketeering, extortion, money laundering and other crimes. A parade of former associates testified against him in a two-month trial, telling of the killing of rival hoodlums and others who had been identified as informers.

Bulger, who exchanged obscenities with some of his accusers, did not take the stand.

In August 2013, the jury convicted him of 31 of 32 counts, including participation in 11 murders, while saying that the prosecution did not prove his involvement in seven others. No verdict was reached in the death of one of two slain women.

The judge later sentenced Bulger to two life terms plus five years. She also ordered him to pay US$19.5 million in restitution to his victims' families and to forfeit US$25.2 million to the government.

After his incarceration, the story of Bulger continued to generate publicity.

In 2014, a documentary, Whitey: The United States Of America V. James J. Bulger, examined the Bulger case through interviews with the prosecution and defense teams and members of victims' families.

The 2015 movie Black Mass, starring Johnny Depp as Bulger, was based on a 2000 book of the same name by Boston Globe journalists Dick Lehr and Gerard O'Neill.