NEW YORK (NYTIMES) - After Russia invaded Ukraine in February, the United States slapped bans on Russian energy sources from oil to coal.

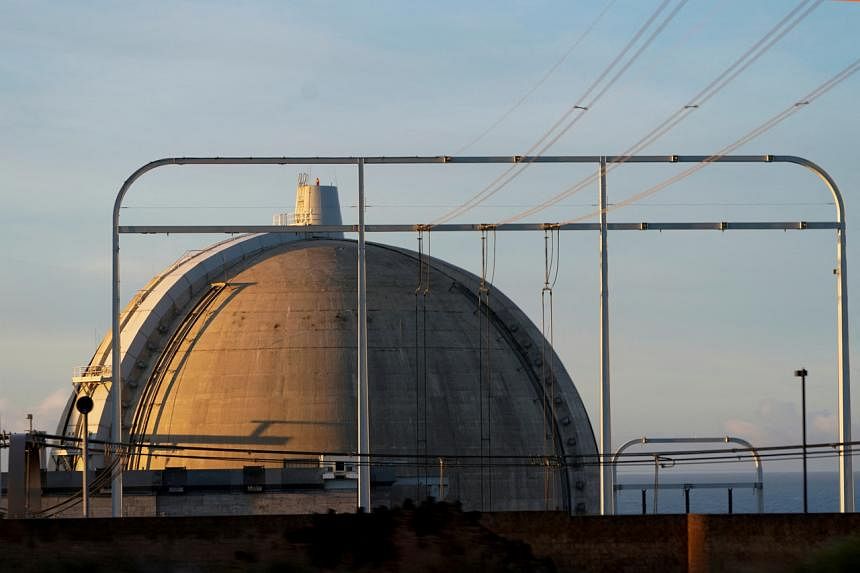

But one critical Russian energy import was left alone: Uranium, which the United States relies on to fuel more than 90 nuclear reactors around the country.

That dependence on Russia is breathing life into ambitions to resurrect the uranium industry around the American West - and also evoking fears of the industry's toxic legacy of pollution.

With some of the most coveted uranium lodes found around Indigenous lands, the moves are setting up clashes between mining companies and energy security hawks on one side and tribal nations and environmentalists on the other.

Arizona's Pinyon Plain Mine, less than 16km from the Grand Canyon's southern rim, is emerging as ground zero for such conflicts.

The Havasupai Tribe, whose people have lived in the canyonlands and plateaus of the Grand Canyon since time immemorial, call the area of the mining site Mat Taav Tiijundva - "Sacred Meeting Place" in a rough translation.

But since Russia's invasion, mining executives have seen the site as something else: the tip of the spear in their jostling to advance American uranium projects.

"We have the ability to reduce dependence on Russian uranium right now," said Mr Mark Chalmers, chief executive of Energy Fuels, the Colorado company that owns Pinyon Plain and is fighting in court to ramp up uranium production.

The Grand Canyon went through a uranium mining boom in the 1950s that ebbed by the 1980s, when Pinyon Plain was built. Near Havasupai burial sites, and targeted by legal battles nearly since its inception, the mine has never been fully operational.

But the mine produces water heavy in arsenic and uranium as a result of drilling several years ago that punctured an aquifer, provoking fears that the site could contaminate Havasupai water supplies.

"It's easy to use this war as an excuse to advance this project," said Mr Stuart Chavez, a member of the Havasupai Tribal Council, about the Pinyon Plain Mine, which is one of numerous already permitted uranium sites in states including Arizona, Utah and Wyoming that could quickly increase activity if sanctions are levied on Russian uranium.

He contends the US could turn to Canada or other friendly nations to make up for Russian uranium if the imports end.

The Russian uranium imports originated in the Cold War's aftermath. Aiming to curb the risk of nuclear war, the United States struck a deal in 1992 to buy enriched uranium that had been used in thousands of scrapped Russian nuclear warheads.

Called Megatons to Megawatts, the nonproliferation programme lasted until 2013. Still, even when Russia annexed the Crimean Peninsula in 2014 and went on to invade Ukraine this year, the United States kept importing large quantities of Russian uranium.

As the Russian uranium sales took hold, the American uranium industry idled mines around the West, a result of the collapse of prices after the end of the Cold War arms race and of a slowdown in construction of new nuclear plans.

Now the industry is finding powerful support in Washington.

Senator John Barrasso, Republican-Wyoming, introduced a Bill in March to ban Russian uranium imports partly as a way to revive American mines.

Legislators in the House of Representatives, including Representative Henry Cuellar, Democrat-Texas, introduced their own bipartisan Bill in March calling for a ban.

"A robust domestic supply chain for nuclear fuel has never been more important for our nuclear fleet," Mr Scott Melbye, president of the Uranium Producers of America, a trade group, said in testimony before the Senate in March. "The sooner we decouple our nuclear industry from Russia, the sooner Western nuclear markets can get to work to fill the gap."

The measures have not advanced in the Democratic-controlled chambers in large part because the United States still relies so heavily on Russian uranium.

While energy sources like wind and solar are gaining ground, nuclear power comprises about 19 per cent of the electricity produced in the US the world's largest uranium consumer.

As nuclear power companies seek ways to expand mining and jump-start the enrichment supply chain in the US, opponents of Pinyon Plain warn it could produce an outcome similar to the hundreds of abandoned uranium mines still emitting dangerous radiation levels on Indigenous lands.

"This specific site is sacred for us, dotted with burial places and remains of homes and sweat lodges," said Ms Carletta Tilousi, a former Havasupai tribal council member who has been fighting the mine for decades.

Like other uranium projects around the country, activity at the mine was suspended in the 1990s when uranium prices crashed. But the mine's owners managed to advance the project, even after the Obama administration announced a 20-year ban in 2012 on new uranium mining around the Grand Canyon.

Owners of the mine, which was grandfathered in before the moratorium, have prevailed in one legal challenge after another.

In February, a federal appeals court sided with the US Forest Service in a ruling against the Havasupai and three environmental groups seeking to prevent the mine from operating.

Mr Chalmers called the ruling a victory for energy security, contending that the mine had enough uranium to provide the entire state of Arizona with electricity for one year.

"It's the highest-grade uranium mine in the United States," said Mr Chalmers, who has extensive experience in Australia and former Soviet republics.

Eyeing uranium prices, which have shot up more than 30 per cent since the war flared up, he also said Energy Fuels was close to negotiating contracts to supply uranium to nuclear power plant operators in the United States.

At the same time, he argued that the mine would not be harmful to the Havasupai.

Hydrology professor David Kreamer, an authority on groundwater contaminants at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, disputed that assertion.

"I'm all for mining if it's done responsibly with proper safeguards," Prof Kreamer said. But he called Pinyon Plain a potential "time bomb" that could have detrimental effects in a decade or so.

Prof Kreamer said he was especially concerned about drilling activity at the mine that pierced an aquifer several years ago, releasing millions of gallons of water high in both uranium and arsenic.