NEW YORK (NYTIMES) - Researchers have managed to tame pancreatic cancer in a woman whose cancer was far advanced and after other forms of treatment had failed.

The experiment that helped her is complex and highly personalised and is not immediately applicable to most cancer patients.

Another pancreatic cancer patient, who received the same treatment, did not respond and died of her disease.

Nonetheless, a leading journal - The New England Journal of Medicine - published a report of the study Wednesday (June 1).

Dr Eric Rubin, the journal's editor-in-chief, called the proof of concept experiment "an important step along the way" to devising similar treatments that might be applicable to lung, colon and other cancers.

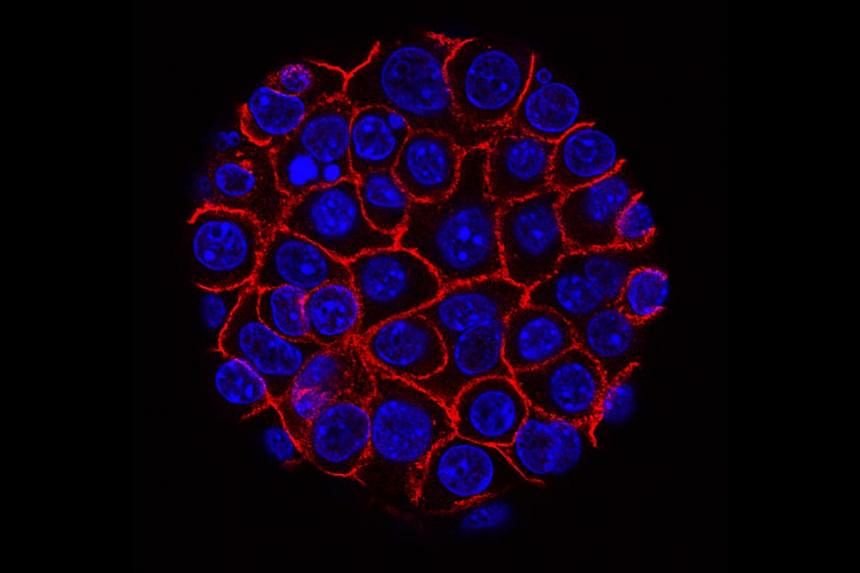

The experiment involved genetically reprogramming the patient's T cells, a type of white blood cell of the immune system, so they can recognise and kill cancer cells. The technique was developed by Dr Eric Tran and Dr Rom Leidner of the Earle A. Chiles Research Institute, a division of Providence Cancer Institute in Portland, Oregon.

To turn a cancer patient's T cells into a living drug, the researchers had to overcome serious challenges.

Pancreatic cancer is one of the most difficult to treat. While new treatments have allowed patients with other cancers to live longer and to have a better quality of life, pancreatic cancer has stubbornly resisted these advances. Fewer than 10 per cent of patients live past five years.

For most patients, said Dr William Jarnagin, a pancreatic cancer specialist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre, who was not involved in the current experiment, the cancer has already spread by the time it is discovered.

Even when the tumours are caught in the pancreas and surgically removed, about 85 per cent of patients have recurrences.

"Our treatments are not doing the job," Dr Jarnagin said.

The technique described in the new paper, "is not off-the-shelf," Dr Tran said. He added that "it takes specialised facilities and expertise to manufacture the T cells." But, Dr Leidner said, "the beauty of it" is that the reprogrammed T cells will only attack cancer cells. Other cells will be left alone.

The first problem in trying to entice T cells to kill cancer cells is that mutated proteins that drive the growth of cancer are hidden inside cells.

There is, though, a hint to the immune system that the cancer cells are abnormal. They contain fragments of mutated cancer proteins on their surface, "kind of like molecular bread crumbs," Dr Leidner said. The challenge was to get T cells to see those crumbs.

The solution employed was to collect the patient's own T cells and genetically modify them in the lab to recognise and attach to those bits of mutated proteins. Then the T cells were infused back into the patient.

In this case the target was Kras, a mutated protein implicated in 25 per cent of all cancers, including about 95 per cent of pancreas cancers, 40 per cent of colon cancers and a third of lung cancers.

"Folks have been trying to target Kras immunologically for more than 20 years," said Dr Robert Vonderheide, a pancreatic cancer specialist and director of the University of Pennsylvania's Abramson Cancer Centre.

The mutated Kras gene "is such a bull's-eye," Dr Vonderheide said, that killing cancer cells by attacking cells with Kras mutations has "major implications."

But the encouraging result comes with some real caveats. For starters, it is not clear why the other patient who died did not respond to the therapy.

Dr Elizabeth Jaffee, a pancreatic cancer specialist at Johns Hopkins Medicine, also highlighted the location of the patient's metastases, or where the cancer had spread to.

Metastases arose only in the patient's lungs. Most pancreatic cancer patients have metastases in their liver that are more difficult to treat.

"I would like to see liver lesions go away," Jaffee said.

Ms Kathy Wilkes, the patient who was successfully treated, is 71 and lives in Ormond-by-the-Sea, Florida. It is too soon to know if the cancer will come roaring back.

Ms Wilkes' cancer was severe.

"This lady had had all of the available treatments and was failing," said Dr Jarnagin, who did not treat Ms Wilkes but reviewed her case. Usually, in such cases, the cancer has developed resistance to any additional treatments.

"For most in that situation, the cancer is going to win - soon," he said.

Ms Wilkes first noticed symptoms that were later attributed to pancreatic cancer in 2015. She was tired, lethargic and had bouts of intense pain. At first, tumours did not appear on scans. But by early 2018, a tumour showed up - a 3.5cm mass in the head of her pancreas.

She had chemotherapy followed by a gruelling operation - the Whipple procedure - in which surgeons remove the head of the pancreas, the first part of the small intestine, the gallbladder and the bile duct. Then she had more chemotherapy, followed by radiation and even more chemotherapy.

The cancer was gone from her pancreas, but nodules appeared in her lungs - metastases. The chemotherapy and radiation continued throughout 2018.

"I just went through with it. I certainly wasn't ready to die," Ms Wilkes said. "I had this voice inside saying, 'You can best this one.' "