Although it has been two weeks since US President Donald Trump signed the executive order temporarily barring travellers and refugees from seven Muslim-majority countries, the ban remains a source of much confusion.

At times, it felt like there were multiple, different interpretations of what it meant, both in the courts and among government employees meant to enforce the directive.

Some judges outlawed parts of it, while others decided that the order should be allowed to stand. It wasn't until a judge in Washington state named James Robart issued a "temporary restraining order" that US government agencies fully stopped enforcing the restrictions.

Today, the travel ban exists in a sort of limbo - temporarily on hold - but with the possibility of a court reinstating it at any time.

For many attempting to track the proceedings from afar, the many twists and turns in the saga can be difficult to make sense of.

One big question, for instance, is why a judge sitting in a courthouse in Seattle was able to override an order from the President in the White House.

The answer lies in the unique way the US has set up its court system.

While most people are familiar with the US Supreme Court and its position as the highest court in the country, only recently have the lower courts come under the spotlight.

There are two types of courts in the US - state courts and federal courts. State courts are set up by the state and have broad jurisdiction over most cases an ordinary citizen would encounter.

A driver speeding in New York would be dealt with in the state courts there, just as a robber in Los Angeles would be tried in a California state court. The laws against robbery and speeding are largely state laws and have to be dealt with in the state system.

Separate from the state courts are the federal courts, and this is where things really start to get a little more complicated.

Federal courts have been set up in every state, but they deal with only a narrow set of cases - for instance, those where the US government is the one being sued, or where the law allegedly broken is a federal one.

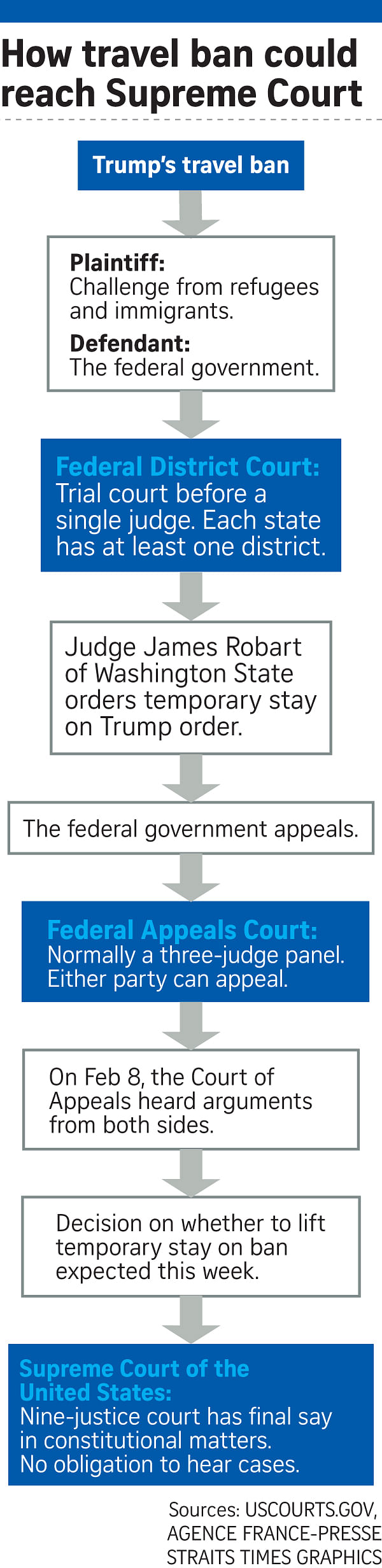

In the case of the travel ban, the defendant was the US government and the law allegedly broken was the protection against religious discrimination provided for under the Constitution. Hence, it was a case clearly meant for the federal courts.

However, that does not mean it goes straight to the Supreme Court. It starts at the lowest rung of the federal court system, known as the US District Court.

There are 94 District Courts, with at least one in each state, and it is at this level that Judge Robart sits.

After the travel ban was put in place, the states of Washington and Minnesota applied at the District Court for it to be temporarily blocked. Judge Robart - who was appointed by then President George W. Bush in 2003 - granted their request and applied it nationally.

While District Court rulings are normally not binding outside their district, judges there do have the power to call for nationwide injunctions.

Judge Robart argued that applying his decision to just two states would not make sense - it would mean a scenario where travel from the banned countries would be allowed in two states but banned at airports everywhere else.

He said that only partially implementing his order would "undermine the constitutional imperative of a uniform Rule of Naturalisation, and Congress' instruction that the immigration laws of the United States should be enforced vigorously and uniformly" - borrowing wording from a 2015 Texas District Court judgment halting one of then President Barack Obama's immigration executive orders nationally.

To be clear, it does not matter what Judge Robart's views are on the legality of the travel ban. His ruling simply puts everything back the way it was until a full trial can take place.

Such a ruling is also not affected by what other District Courts do because they are not dealing with cases where the legality of Judge Robart's order is being challenged. It does not matter if a different judge in a different district declines to grant the same injunction.

The only way that the administration could get the ruling overturned is by appealing to the court that sits a step higher in the hierarchy - known as the US Circuit Court of Appeals.

This is where the case lies today. Yesterday, a Court of Appeals heard arguments from both sides, and said it would soon release a judgment on whether the injunction stands.

Even then, do not expect a quick solution. Regardless of what the Court of Appeals decides, the case could still end up on the desk of the Supreme Court.

That means the saga could drag on for months, even after the original executive order expires.