NEW YORK • Last May, an elderly man was admitted to the Brooklyn branch of Mount Sinai Hospital for abdominal surgery.

A blood test revealed he was infected with a newly discovered germ as deadly as it was mysterious.

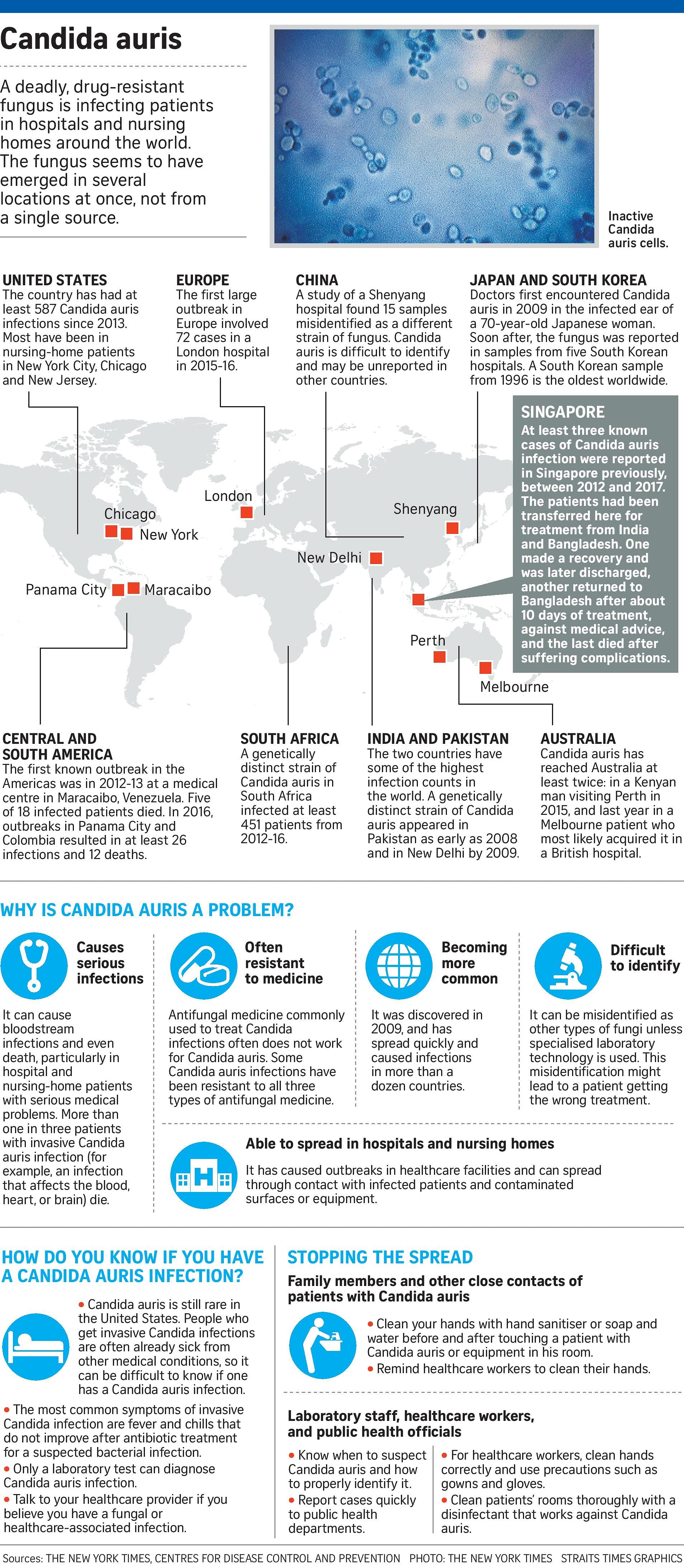

The germ, a fungus called Candida auris, preys on people with weakened immune systems, and it is quietly spreading across the globe.

Over the past five years, it has hit a neonatal unit in Venezuela, swept through a hospital in Spain, forced a prestigious British medical centre to shut down its intensive care unit, and taken root in India, Pakistan and South Africa.

Recently, C. auris reached New York, New Jersey and Illinois, leading the federal Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to add it to a list of germs deemed "urgent threats".

The man at Mount Sinai died after 90 days in the hospital, but C. auris did not. Tests showed it was everywhere in his room, so invasive was it that the hospital needed special cleaning equipment and had to rip out some of the ceiling and floor tiles to eradicate it.

C. auris is so tenacious, in part, because it is impervious to major anti-fungal medications.

Resistant germs are often called "superbugs", but this is simplistic because they do not typically kill everyone.

Instead, they are most lethal to people with immature or compromised immune systems, including newborns and the elderly, smokers, diabetics and people with autoimmune disorders who take steroids that suppress the body's defences.

Scientists say that unless more effective new medicine is developed and the unnecessary use of antimicrobial drugs is sharply curbed, risk will spread to healthier populations.

A study the British government funded projects that if policies are not put in place to slow the rise of drug resistance, 10 million people could die worldwide of all such infections in 2050, eclipsing the eight million expected to die that year from cancer.

Antibiotics and antifungals are both essential to combating infections in people. But antibiotics are also used widely to prevent disease in farm animals, and antifungals are applied to prevent agricultural plants from rotting.

Some scientists cite evidence that rampant use of fungicides on crops is contributing to the surge in drug-resistant fungi infecting humans.

Yet, as the problem grows, it is little understood by the public - in part because the very existence of resistant infections is often cloaked in secrecy.

Even the CDC, under its agreement with states, is not allowed to make public the location or name of hospitals involved in outbreaks.

All the while, the germs are easily spread - carried on hands and equipment inside hospitals; ferried on meat and manure-fertilised vegetables from farms; transported across borders by travellers and on exports and imports.

C. auris is one of dozens of dangerous bacteria and fungi that have developed resistance. Yet, like most of them, it is a threat that is virtually unknown to the public.

Dr Lynn Sosa, Connecticut's deputy state epidemiologist, said she now saw C. auris as the top threat among resistant infections. "It is pretty much unbeatable and difficult to identity," she said.

Nearly half of patients who contract C. auris die within 90 days, according to the CDC.

Yet, the world's experts have not nailed down where it came from in the first place.

"It is a creature from the black lagoon," said Dr Tom Chiller, who heads the fungal branch of the CDC, which is spearheading a global detective effort to find treatments and stop the spread.

In late 2015, Dr Johanna Rhodes, an infectious disease expert at Imperial College London, received a panicked call from the Royal Brompton Hospital, a British medical centre outside London. C. auris had taken root there months earlier, and the hospital could not clear it.

Under her direction, hospital workers used a special device to spray aerosolised hydrogen peroxide around a room used for a patient with C. auris, the theory being that the vapour would scour each nook and cranny.

They left the device going for a week. Then they put a "settle plate" in the middle of the room with a gel at the bottom that would serve as a place for any surviving microbes to grow, Dr Rhodes said.

Only one organism grew back - C. auris.

The hospital, a speciality lung and heart centre that draws wealthy patients from the Middle East and around Europe, alerted the British government and told infected patients, but made no public announcement.

This hushed panic is playing out in hospitals around the world.

The secrecy infuriates patient advocates, who say that people have a right to know if there is an outbreak so they can decide whether to go to a hospital.

Dr Kevin Kavanagh, a physician in Kentucky and board chairman of Health Watch USA, a non-profit patient advocacy group, said: "You wouldn't tolerate this at a restaurant with a food poisoning outbreak."

The symptoms - fever, aches and fatigue - are seemingly ordinary. But when a person gets infected, particularly someone already unhealthy, such commonplace symptoms can be fatal.

The first time doctors encountered C. auris was in the ear of a woman in Japan in 2009 (auris is Latin for "ear"). It seemed innocuous at the time, a cousin of common, easily treated fungal infections.

The CDC investigators theorised that C. auris started in Asia and spread across the globe.

But when the agency compared the entire genome of C. auris samples from India and Pakistan, Venezuela, South Africa and Japan, it found that its origin was not a single place, and there was not a single C. auris strain.

The genome sequencing showed that there were four distinctive versions of the fungus, with profound differences.

Dr Chiller theorises that C. auris may have benefited from the heavy use of fungicides. As azole fungicides began destroying more prevalent fungi, an opportunity arrived for C. auris to enter the breach - a germ that had the ability to readily resist fungicides.

NYTIMES

Things to know about the germ

A mysterious and dangerous infection caused by the fungus Candida auris has emerged around the world.

It is resistant to many antifungal medications, placing it among a growing number of germs that have evolved defences against common medicine.

Here are some facts about it.

Q: What is Candida auris?

A: It is a fungus that can cause dangerous and life-threatening infections if it gets into the bloodstream.

Scientists first identified it in 2009 in a patient in Japan.

In recent years, it has emerged around the world, largely in hospitals and nursing homes.

There have been 587 C. auris cases reported in the United States, according to the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), most of them in New York, New Jersey and Illinois.

Q: Why is it so dangerous?

A: C. auris is often resistant to major antifungal drugs that are typically used to treat such infections.

The CDC said that more than 90 per cent of C. auris infections are resistant to at least one such drug, while 30 per cent are resistant to two or more major drugs.

Once the germ is present, it is hard to eradicate from a facility. Some hospitals even had to rip out floor and ceiling tiles to get rid of it.

Q: Who is at risk?

A: People with compromised or weakened immune systems are the most vulnerable. These include elderly people and people who are already sick. In at least one case, newborns were infected at a neonatal unit.

People with weakened immunity are likely to have more trouble fighting off an initial invasion by C. auris and are likely to be in settings where the infection is more prevalent, such as hospitals and nursing homes.

Q: Why haven't people heard about this?

A: The rise of C. auris has been little publicised in part because it is so new.

But also, outbreaks have at times been played down or kept confidential by hospitals, doctors and even governments.

Some hospitals and medical professionals argue that because precautions are taken to prevent the spread, publicising an outbreak would scare people unnecessarily.

Q: Can I do anything to protect myself?

A: The symptoms of C. auris - fever, aches, fatigue - are not unusual, so it is hard to recognise the infection without tests.

The good news is that the threat of becoming sick with C. auris is very low for healthy people going about their daily lives.

If you or a loved one is in a hospital or nursing home, you can ask if there have been cases of C. auris there.

If so, it is reasonable to request that proper infection-control precautions are taken.

NYTIMES