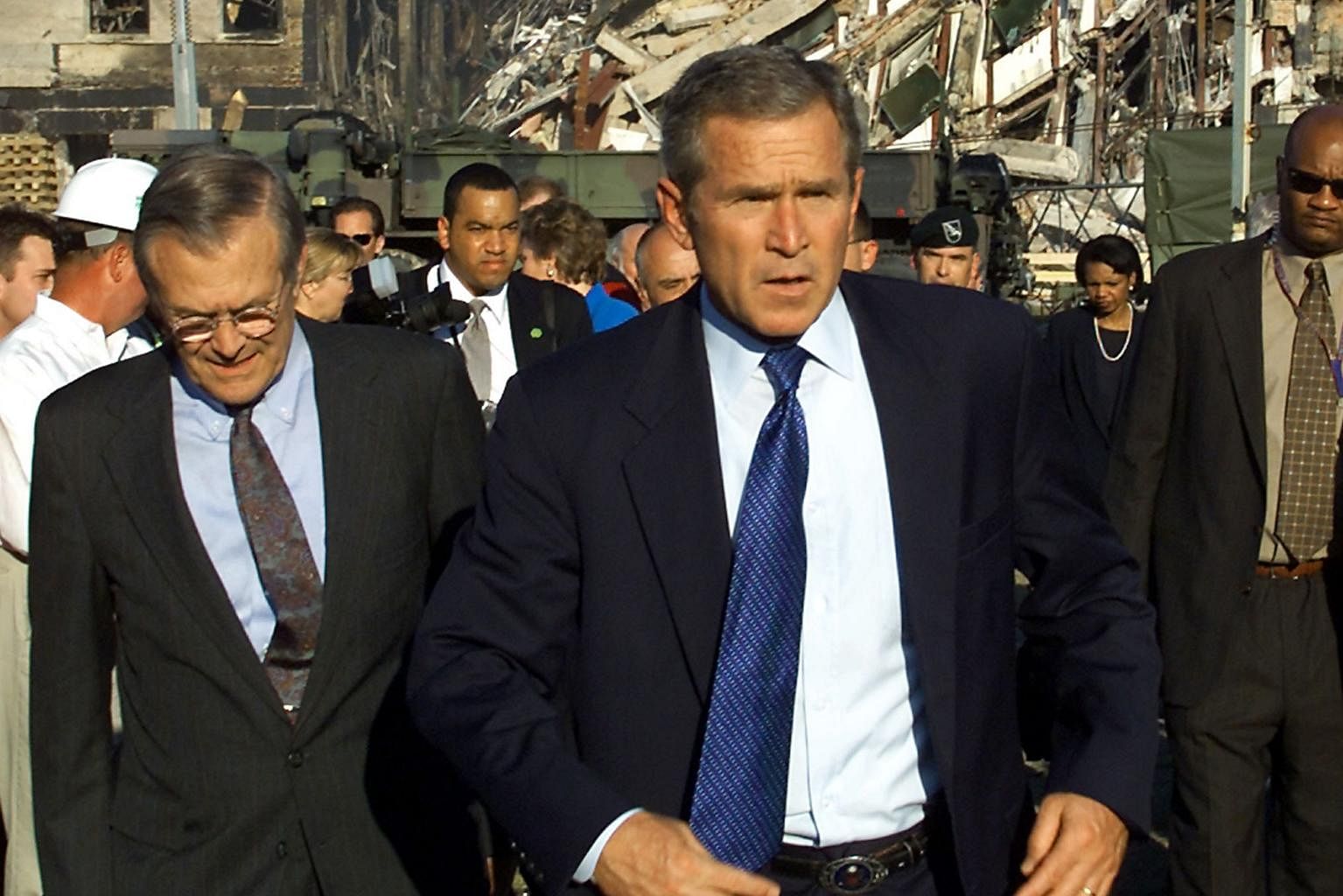

When President George W. Bush declared the start of a global war on terror in 2001, one week after the 9/11 attacks, he envisioned a far-reaching, lengthy campaign aimed at eradicating terrorism itself.

"Our war on terror begins with Al-Qaeda, but it does not end there," he told Congress.

"It will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped and defeated."

Twenty years later, success is mixed at best.

The United States indeed greatly weakened Al-Qaeda and killed its leader Osama bin Laden. The Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), Al-Qaeda's most potent offshoot which rose to prominence after 2011, has been decimated in Syria.

Nor has America had another major foreign terrorist attack on its soil since 9/11.

"That reality, however, does not erase the enormous excesses and warped risk calculations that defined Washington's response to 9/11," Mr Ben Rhodes, an Obama-era deputy national security adviser, wrote in Foreign Affairs.

Framing counter-terrorism as a long-spanning, global war led to overreach and unintended consequences, he argued, noting: "The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq became about far more than taking out Al-Qaeda."

The US-led invasion of Afghanistan lasted two decades, expanding from a successful effort to topple the Taliban government to a drawn-out occupation and counter-insurgency mission.

In Iraq - which had been more tenuously linked to the war on terror in the first place - the US was mired in a decade-long occupation.

After ousting Saddam Hussein's regime, the US embarked on an ambitious post-war reconstruction before withdrawing in 2011.

America's global war on terror has included military action in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Pakistan, the Philippines, Somalia, Yemen and elsewhere, as well as controversial unmanned drone strikes.

This vast range has raised questions over whether the Congress' authorisation of the President to use military force against 9/11 perpetrators has far exceeded its original intent, the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) noted.

The costs of these wars have been astronomical. Brown University's Costs of War project estimates that nearly one million lives have been lost, from US troops and civilians to journalists and aid workers killed directly by war.

Project co-founder Neta Crawford said the tally was likely a "vast undercount of the true toll", which did not take into account indirect deaths caused by displacement, disease and other disasters of war.

The wars have cost the US federal government US$8 trillion (S$10.7 trillion), a bill that includes care for veterans.

And, for all that cost, terrorism today is more global than it was in 2001 when it was mostly centred in the Middle East.

Al-Qaeda and ISIS, for instance, have a wider reach than they did in 2001, with networks in Africa, South Asia and South-east Asia.

There are also four times as many Salafi-jihadi terrorist groups designated by the US State Department now than in 2001, CFR senior fellow for counter-terrorism and homeland security Bruce Hoffman noted in an event on Wednesday.

While Al-Qaeda has been incontestably weakened, "the problem is the ideology that underpinned it continues to have tremendous resonance" in attracting recruits, he said.

America's actions have also created unintended consequences that came back to bite it, notably its invasion of Iraq and withdrawal from it, which created a power vacuum in which ISIS flourished.

The Wilson Centre's Asia programme deputy director Michael Kugelman argued that the US response to 9/11 ushered in more instability in South Asia, in ways that backfired on America.

The prolonged war in Afghanistan resulted in tens of thousands more deaths, and contributed to the emergence of the Pakistani Taliban in 2007, Mr Kugelman said in a panel.

"It also caused anti-Americanism to increase in a big way in the region", particularly in Pakistan, the epicentre of America's drone war, he said.

Some terrorists who emerged in South Asia later targeted Americans, he said, citing Pakistan-born naturalised US citizen Faisal Shahzad and his attempt to bomb Times Square in 2010.

Not only were America's enemies changed by the war on terror, but America itself was changed as well. In its hunt for terrorists, "the US government abased some core American values and principles of justice", wrote Dr Hoffman.

It turned to imprisoning people indefinitely, many without charge.

Some 39 detainees remain today in the Guantanamo Bay facility, including Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the Pakistani accused of masterminding 9/11. His case remains mired in pre-trial proceedings.

The US government also authorised Central Intelligence Agency "black sites" - secret prisons overseas where terrorists were held and tortured for information.

Photos of inmates abused by US troops at Iraq's Abu Ghraib prison complex became some of the enduring images of the war on terror.

Today, experts note America appears to recognise the war on terror cannot be won in a conventional sense. Terrorism itself, as a strategy, has not been defeated and cannot be.

"Instead of a decisive victory, the United States appears to have settled for something less ambitious: Good enough," wrote Georgetown University professor and counter-terrorism expert Daniel Byman in Foreign Affairs.