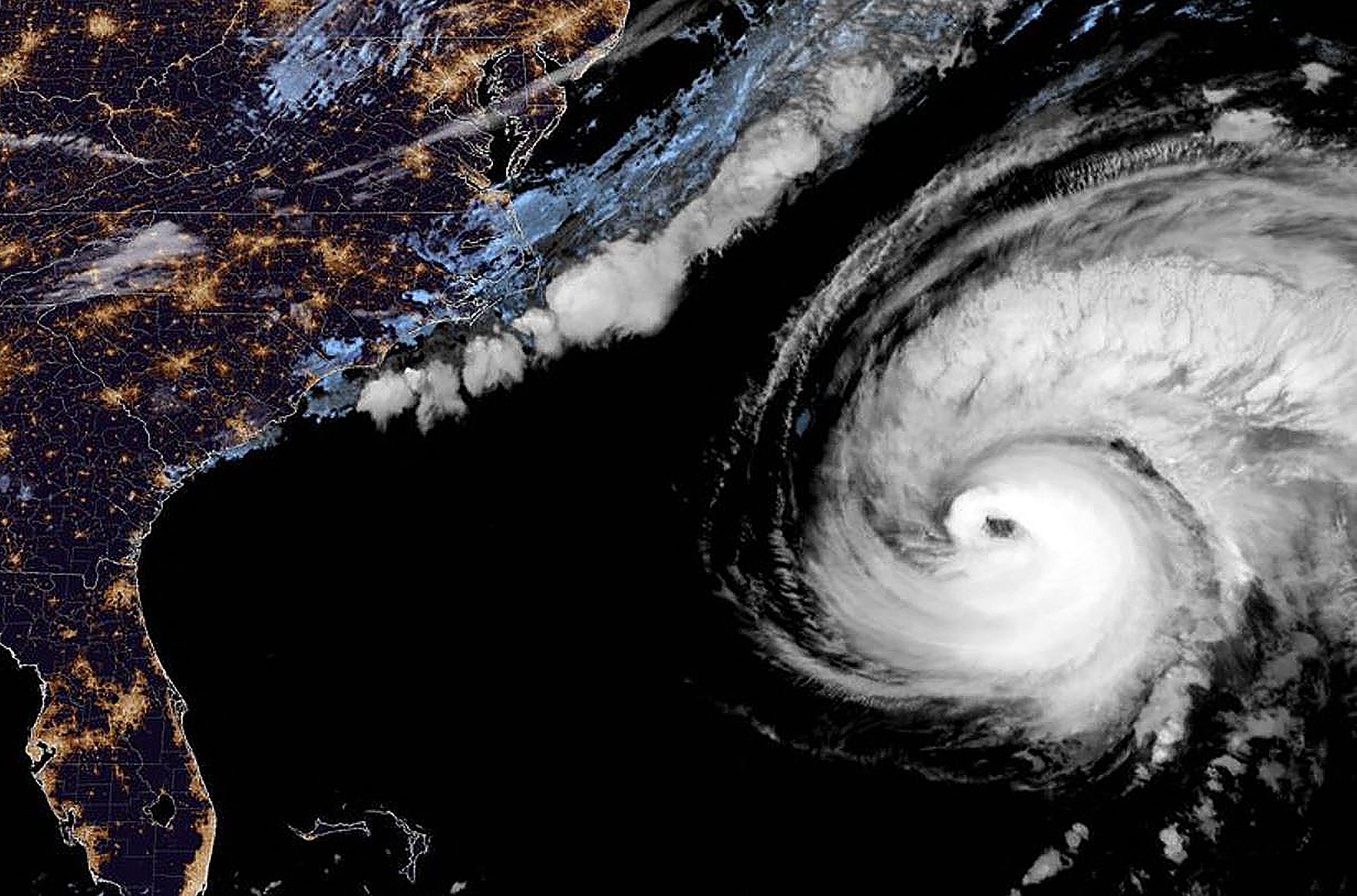

WASHINGTON - Hurricane Fiona was moving away from Bermuda on Friday morning after lashing the island in the Atlantic with high winds and heavy rain on its way north to eastern Canada.

Fiona, the strongest storm of the Atlantic hurricane season so far, was about 201km north of Bermuda as of 8am Eastern time, the National Hurricane Centre said.

It was moving at 40km and producing maximum sustained winds of 201kmh.

A hurricane warning was in effect for Nova Scotia and other parts of Atlantic Canada and eastern Quebec, areas that the storm was expected to approach later on Friday as a "post-tropical" cyclone.

Forecasters in Canada said Fiona's heavy rainfall and powerful hurricane-force winds would arrive beginning early on Saturday.

Forecasters did not anticipate that Fiona would threaten the East Coast of the United States.

The Bermuda Weather Service said parts of the island had experienced hurricane-force winds early on Friday, including a 160kmh gust on the western side of the island. Around 2.54cm to 7.62cm of rain were expected.

"The closest point of Fiona has passed us, and I think we have come through this here in pretty good shape," Mr Michael Weeks, Bermuda's minister of national security, said in a statement on Facebook on Friday.

He said emergency crews would assess any damage early in the morning and advised residents to stay off the roads and in their homes, as powerful winds and heavy bands of rain were still affecting the island.

As of early Friday, about 29,000 customers were without power across the island, according to Belco, Bermuda's sole supplier of electricity.

The company said on its website that its crews would not be able to restore power until hurricane-force winds and storm conditions subsided.

Fiona was expected to approach Nova Scotia later on Friday with hurricane-force conditions, bringing 3-6 inches of rain to Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and western Newfoundland, and potentially up to 10 inches in some areas, the hurricane centre said.

Hurricane or tropical storm warnings from the Canadian government were in effect as of 3am Eastern time on Friday for parts of Atlantic Canada and eastern Quebec.

The government said waves in some parts of the Gulf of St Lawrence could be higher than about 11.8m.

In Bermuda, officials have warned that storm surge from Fiona could bring high water levels and produce large, destructive waves.

Public schools and government offices, which operated on Thursday, were closed Friday.

Bermudans were making preparations for Fiona on Thursday. Residents of the island, which is believed to have inspired Shakespeare's The Tempest, said that living there comes with the usual tribulations of a hurricane season.

"We are a country of storms," said Ms Kristin White, a writer and entrepreneur living in the 410-year-old town of St George's.

"It is in our blood and bone. The structures here date back to the 17th century, so I'm fairly confident that the buildings will be fine. Knock on cedar; knock on limestone."

The smell of the storm hung in the air, and salty spray blanketed vehicles before the hurricane's anticipated arrival.

Business owners boarded up before an advisory to remain home took effect on Thursday night.

A government official said the island had built up a robust system to deal with hurricanes, which he said have been "growing more frequent and certainly more destructive" over the last 20 years.

"We have a very rigid planning regime that ensures that most of our structures are built to hurricane-strength levels, and this has stood the test of time for Bermuda," said Mr Walter Roban, the minister of home affairs.

Fiona, which formed as a tropical storm on Sept 15, has battered parts of the Caribbean in the past week, including Puerto Rico, which experienced widespread power outages.

As of early Friday, about 928,000 customers in Puerto Rico were still without electricity, according to poweroutage.us, which tracks interruptions.

Governor Pedro Pierluisi of Puerto Rico said earlier this week that it would take at least a week for his government to estimate how much damage Fiona had caused.

The rain in parts of central, southern and southeastern Puerto Rico had been "catastrophic", he said at a news conference.

At least four deaths have been attributed to Fiona: two in the Dominican Republic and one each in Puerto Rico and Guadeloupe, which was struck by the storm last Saturday.

Forecasters were monitoring two other weather systems in the Atlantic: Tropical Storm Gaston, which formed on Tuesday, and a tropical depression that formed early on Friday and would become Tropical Storm Hermine if it strengthens much further.

Gaston was 135 miles north-northwest of the Azores in the North Atlantic early on Friday, with maximum sustained winds of 96.5kmh.

The storm's centre was expected to move near or over portions of the Azores from Friday night through on Saturday, the hurricane centre said.

Gaston was forecast to begin to weaken over the next few days, though a tropical storm warning was in effect for parts of the Azores.

The tropical depression was about 965km east-southeast of Jamaica on Friday morning and moving west-northwest at 21kmh, according to the hurricane centre.

The Atlantic hurricane season, which runs from June through November, had a relatively quiet start, with only three named storms before Sept 1 and none during August, the first time that had happened since 1997.

Storm activity picked up in early September with Danielle and Earl, which formed within a day of each other.

The links between hurricanes and climate change have become clearer with each passing year.

Data shows that hurricanes have become stronger worldwide over the past four decades.

A warming planet can expect stronger hurricanes over time and a higher incidence of the most powerful storms - though the overall number of storms may drop, because factors like stronger wind shear could keep some weaker storms from forming.

Hurricanes are also becoming wetter because there is more water vapour in the warmer atmosphere; storms such as Hurricane Harvey in 2017 produced far more rain than they would have without human effects on the climate, scientists have suggested.

Also, rising sea levels are contributing to higher storm surges, the most destructive elements of tropical cyclones.

In early August, scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration issued an updated forecast for the rest of the season, which still predicted an above-normal level of activity.

In it, they said that the season could include 14-20 named storms, with six to 10 turning into hurricanes that could sustain winds of at least 119kmh.

Three to five of those could strengthen into what the agency calls major hurricanes - Category 3 or stronger - with winds of at least 178kmh.

Last year, there were 21 named storms, after a record-breaking 30 in 2020.

For the past two years, meteorologists have exhausted the list of names used to identify storms during the Atlantic hurricane season, an occurrence that had happened only one other time, in 2005. NYTIMES