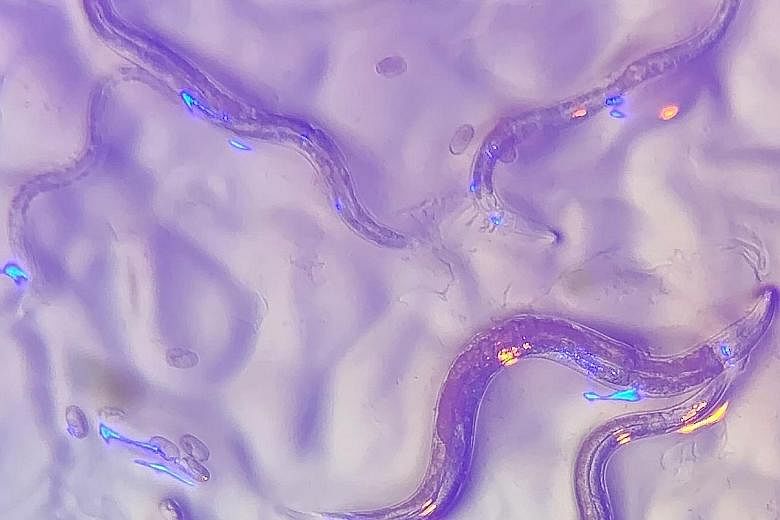

In the warm, fetid environs of a compost heap, tiny roundworms feast on bacteria. But some of these microbes produce toxins, and the worms avoid them.

In the laboratory, scientists curious about how the roundworms can tell what is dinner and what is dangerous often put them on top of mats of various bacteria to see if they wriggle away. One microbe species, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, reliably sends them scurrying.

But how do the worms, common lab animals of the species Caenorhabditis elegans, know to do this? Mr Dipon Ghosh, then a graduate student in cellular and molecular physiology at Yale University, wondered if it was because they could sense the toxins produced by the bacteria. Or might it have something to do with the fact that mats of P. aeruginosa are a brilliant shade of blue?

Given that roundworms do not have eyes, cells that obviously detect light, or even any of the known genes for light-sensitive proteins, this seemed a bit far-fetched. It was not difficult to set up an experiment to test the hypothesis, though: Mr Ghosh, who is now a postdoctoral researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, put some worms on patches of P. aeruginosa. Then he turned the lights off.

To the surprise of his adviser, Mr Michael Nitabach, the worms' flight from the bacteria was significantly slower in the dark, as if not being able to see kept the roundworms from realising they were in danger. "When he showed me the results of the first experiments, I was shocked," said Mr Nitabach, who studies the molecular basis of neural circuits that guide behaviour at Yale School of Medicine.

In a series of follow-up experiments detailed in a paper published in the journal Science, Mr Ghosh, Mr Nitabach and their colleagues established that some roundworms respond clearly to that distinctive pigment, perceiving it - and fleeing from it - without the benefit of any known visual system.

How they accomplish this perceptual feat remains a mystery, but the findings hint that the worms may have hacked other cellular warning systems to gain a kind of colour vision.

Nematodes like C. elegans do have an aversion to ultraviolet light and certain wavelengths of visible light, past work has shown, and too much light can affect worms' lifespans. Researchers generally thought of this behaviour as a way to avoid stressful exposure to sunlight.

But using colour to steer their foraging behaviour - that was a new idea. To see if changing the bacteria's colour would have an effect, Mr Ghosh next put worms on a mutated strain of P. aeruginosa that was beige rather than blue.

This time, the worms did not move away any faster whether it was light or dark in the lab. That suggested that they were lacking extra cues from the bacteria's colour.

Mr Ghosh also put the blue pigment - a toxin called pyocyanin - on E. coli, a common food source for the worms. But rather than feasting on the bacteria, he found that they fled rapidly from the microbes when they were well lighted.

Other experiments established that while the worms might sense something unpleasant about the toxin without the presence of the colour, they really got moving when blue was visible.

The researchers tested dozens of roundworm strains and found that while some did not respond to blue, others were extremely sensitive to it, leaving a mat of harmless E. coli if the right coloured light was shining.

Trying to understand how the eyeless creatures were sensing this, the researchers compared the genomes of worms that responded strongly to colour with those that ignored it. They were able to pinpoint several regions of the genomes that correlated with the behaviour.

Then they engineered worms with mutations in genes in those regions to see if the creatures' colour detection abilities were affected. Indeed, they uncovered two genes, jkk-1 and lec-3, that seemed to affect the worms' behaviour if mutated.

It is still unknown how these two genes, which code for proteins with no obvious connection to vision, connect to the worms' enigmatic talent. They may be part of a long bucket brigade of proteins, passing on the message from one to the next that something blue is in the area, until it reaches the worm's neurons and gets the creature moving.

The proteins have been flagged in the past, however, in cellular responses to stressors like ultraviolet light in human and mouse cells, Mr Ghosh said.

If researchers can uncover just how the roundworms are detecting colour, they will have new insight into a surprising behaviour and a handle on how organisms without a traditional visual system may still be able to perceive visible light. It may also be that an evolutionarily ancient way of avoiding stressors has been tuned to blue.