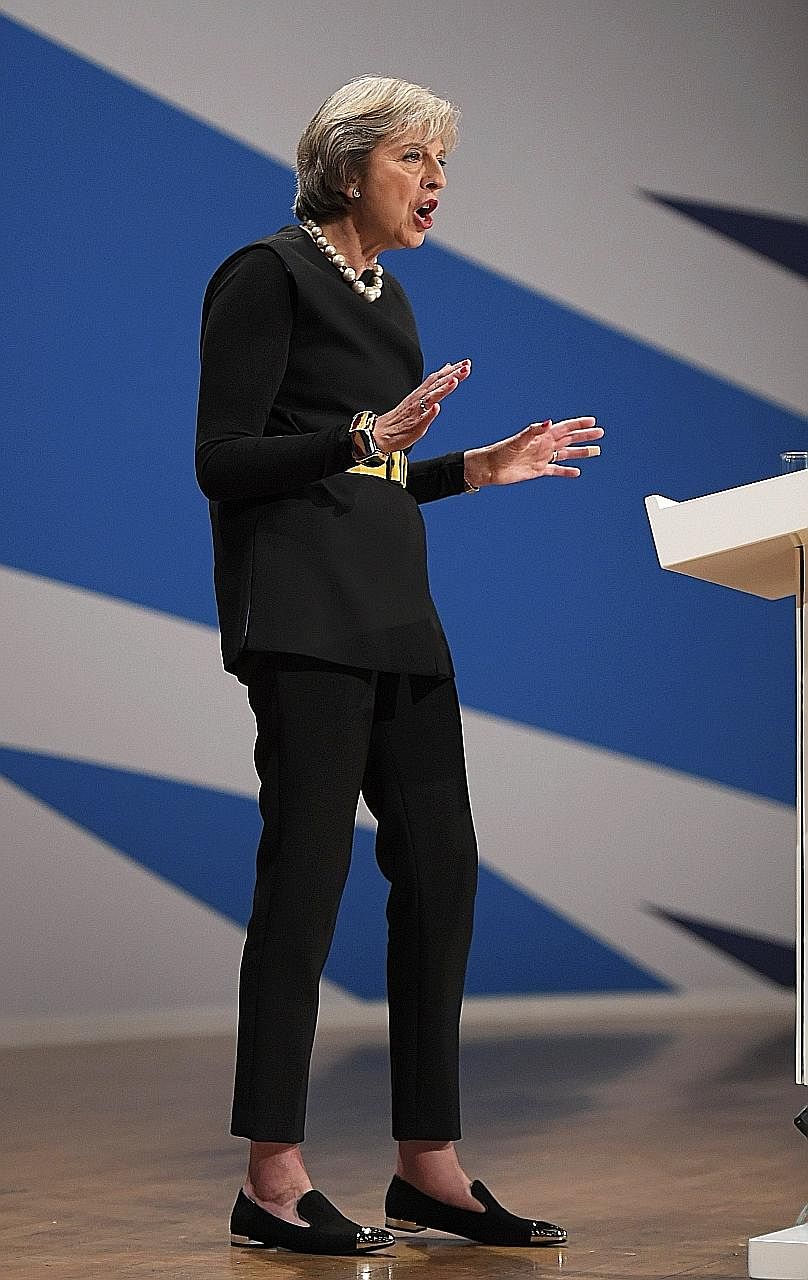

Prime Minister Theresa May's announcement that negotiations for Britain's departure from the European Union will start by March next year and that legislation "to make Britain sovereign and independent again" will shortly be presented to Parliament have ended months of political speculation in London.

But they have done nothing to provide reliable clues about Britain's negotiating stance with the EU. Nor has the British leader offered any guidance to her country's civil servants who are now expected to change almost half a century of European legislation in a matter of just a few years.

Mrs May's first instinct when she came to power in July in the wake of a referendum in which Britons voted by 52 per cent to 48 per cent to leave the EU was to postpone the Brexit negotiations for as long as possible. But that proved untenable, partly because of pressure from European governments, and partly because the dithering merely generated further bickering among the British government's backbenchers.

It was therefore no surprise that the Prime Minister chose her ruling Conservative Party's annual conference as the venue for the announcement that the separation talks with the EU will begin by March.

The timing is not ideal, coming just before both France and Germany hold their main national elections. Still, EU President Donald Tusk hailed the move as providing a "welcome clarity" to European affairs, largely because it offers a clear timetable; according to the EU treaties, once begun, the talks must be concluded in two years.

Yet, although the British leader ended one uncertainty, she hinted at many others, by suggesting an uncompromising negotiating stance. Mrs May claimed to want to forge a "mature, cooperative relationship that close friends and allies enjoy" with Europe, one which maintains Britain's connection with Europe's single trading market. But she also said that Britain will insist on reinstating its border controls on citizens from other EU states, and will no longer be bound by the rulings of the European Court of Justice, the EU's highest court.

Mrs May has been told on innumerable occasions that she cannot protect the benefits of European markets without also accepting the requirement to grant EU citizens freedom of movement in Britain. So, the fact that she has now reiterated her demand to be given a right to impose immigration controls is interpreted by many political observers as an indication that, if no compromise can be reached on this point, she would rather sacrifice Britain's trade access than make concessions on immigration.

But that conclusion may be premature, for the British leader has been careful not to specify what she means by immigration controls. The only conclusion clear at this stage is that Mrs May's ruling Conservatives won't accept a deal which does not include some immigration controls, and neither would the electorate; opinion polls indicate that while 61 per cent of Britons want their country to remain in Europe's single market, about four in five of the electorate do not want to keep borders open to EU nationals. Navigating through these contradictory expectations will be Mrs May's biggest challenge.

The British leader also tried to address clamour among her backbenchers for a swift move to decouple the nation from Europe by announcing that she will be asking Parliament to adopt what she termed as the Great Repeal Bill, one mega-piece of legislation which will overturn decades of EU membership by ending the powers of European Union institutions to regulate in Britain, and by transforming all European legislation into domestic British law.

That merely raises further difficulties. There is no way the British Parliament can just pass a short Act converting laws adopted over a half century; that process will take many years. So, all that the British Premier has done is simply announce the start of a legal adaptation process which will most certainly extend beyond 2020, the year of the next general election.

Still, the move is shrewd - it gives lawmakers a stake in the Brexit process without giving the British Parliament much of a say on the daily negotiations with Europe, which remain firmly under Mrs May's personal control.

For the moment, the British Premier appears to have succeeded in reassuring her supporters that she is ready to move on regaining her country's total sovereignty, while not giving away too many clues about how she proposes to do it.