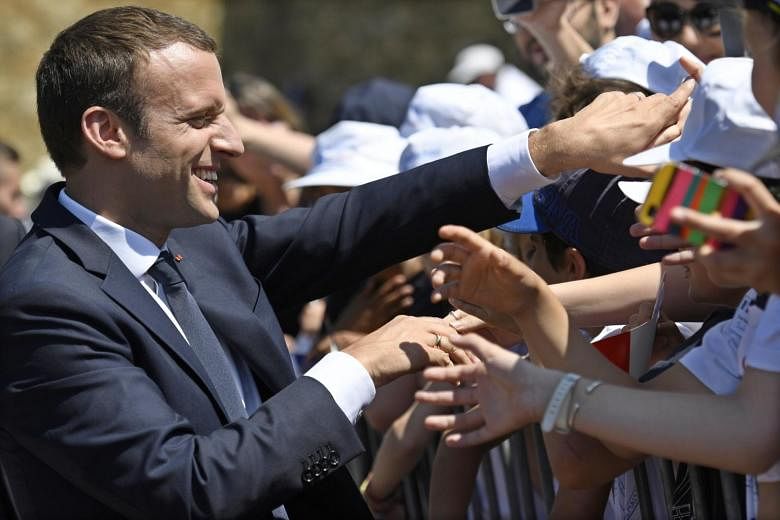

Barely a month after his election as President, Mr Emmanuel Macron completed his political takeover of France after his party secured a crushing overall majority in the country's parliamentary ballots.

With all votes from Sunday's elections counted, President Macron's La Republique en Marche party (LREM) is on course to control 350 seats in the 577-seat National Assembly, a stunning victory made even more remarkable by the fact that the party did not exist as a political movement until early last year.

The parliamentary victory cemented Mr Macron's position as the country's most powerful head of state since Charles de Gaulle introduced the current Constitution half a century ago. But that does not necessarily mean that Mr Macron's plans to implement the deep economic reforms are made any easier.

Notwithstanding his unprecedented electoral victory, doubts linger about how extensive Mr Macron's electoral mandate really is. For France's complex two-round electoral system, in which anyone can compete in the first round but only the top-scoring candidates stand in the second round, produces results which have little bearing on the actual level of support enjoyed by the winners.

Mr Macron's LREM got only 32 per cent of the popular vote in the first round and only 44 per cent in the second, but now controls about 60 per cent of the parliamentary seats.

Furthermore, more than half of the electorate stayed at home on Sunday, one of the lowest turnout levels for any French election in modern times, a figure already seized upon by Mr Macron's opponents to claim that the ballots cannot be considered representative.

Nor should one forget that Mr Macron's own election as President a month ago with two-thirds of the ballots cast in his favour looks impressive only because the choice facing voters was either him or Ms Marine Le Pen, the leader of the far-right National Front. Mr Macron's score in the first round of the presidential elections - a much better gauge of his real personal following - was a far more modest quarter of the electorate.

There is also the difficulty that most of the LREM's newly elected MPs are unknown and new to politics, people handpicked by the President because of their professions, gender or age in an effort to create France's most diverse political movement rather than because they share the same beliefs. They include a former refugee from Rwanda and a professor of mathematics with a penchant for wearing 19th-century-style clothes and spider-shaped brooches and a colourful retired female bullfighter who ultimately failed to be elected but provided plenty of entertainment for the media.

The fact that most of the new MPs have no political experience will initially work in Mr Macron's favour; they owe their existence to him, and will vote on anything the President puts before them. But as time goes by, such a collection of yes men and women could rebound on the President's standing.

For Mr Macron's biggest problem is now, paradoxically, the sheer scale of his victory. The mainstream Socialists, a key pillar of French politics for over a century, are relegated to a fringe movement. They and the hard left combined hold only 46 seats.

The centre-right Republicans did better with 131 seats, thereby remaining the official opposition, but also performed poorly. So did the National Front, which managed to get Ms Le Pen elected to the National Assembly for the first time, but otherwise secured only nine seats, about half of what was predicted.

Soon after the scale of his victory became clear, President Macron appealed to his lawmakers "not to engage in triumphalism, but to remain determined to start working fast with a parliamentary agenda which remains overburdened".

However, the danger remains that, marginalised and rendered impotent, real opposition to Mr Macron will move from Parliament to the streets, and especially to France's powerful trade unions, which remain under the Socialists' control and are adamantly opposed to the President's plans to cut spending, lay off civil servants and liberalise France's labour laws.

All these measures have been attempted by previous French presidents since the 1990s, and invariably failed or were abandoned in the face of massive strikes and demonstrations.

President Macron has served notice that he is made of stronger steel: He has threatened to ram through the changes through emergency decrees, if necessary.

Yet, having won every electoral battle, Mr Macron still has to prove that he has won the biggest battle of all - that of forging a national consensus for economic reform.