As ballots in Britain's general election are counted later on tonight, it won't be only the country's politicians who will be waiting with bated breath for the outcome; so will Britain's opinion pollsters.

For seldom before have the polls been so split in projecting Britain's electoral outcome. And never before has the credibility of opinion pollsters been so much at stake.

Two months ago, when Prime Minister Theresa May announced her intention to hold early elections, opinion polls were giving her ruling Conservatives an average lead of 18 percentage points over the main opposition Labour party; translated into parliamentary seats, the Conservatives would have ended up with more than 400 MPs in the country's 650-strong House of Commons, a crushing majority.

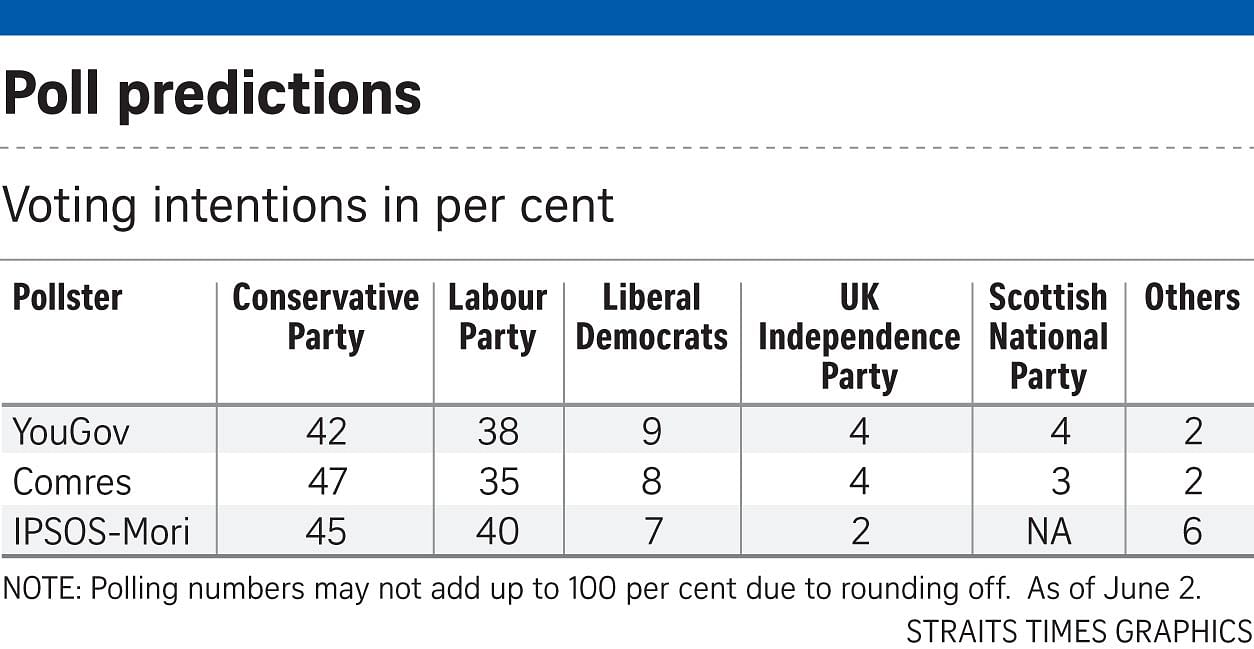

Yet as the electoral campaign progressed, opinion polls shifted all over the place. Some believe the Conservatives' lead over Labour has now shrunk to not more than four points, some maintain that their lead is still in double digits, while one pollster, YouGov, appears to be projecting a hung Parliament tonight, one in which no party has an overall majority.

The credibility of the predictions is important to polling companies, which are still reeling from their failure to predict the outcome of Britain's 2015 general election, when they all assumed the Conservatives would not win, only to see them secure an overall majority.

The industry also did no better during last year's referendum on Britain's membership in the European Union, when pollsters firmly projected a majority for remaining within the EU, while the actual result was a victory for Brexiters.

After these failures, British pollsters tweaked their working methods, improved their surveys and planned to present a more convincing service during the current campaign. But instead, they merely succeeded in confusing everyone.

To some extent, the media is responsible for the current confusion, partly because news outlets prefer the sensationalist over the mundane, and partly because media correspondents either do not understand statistics, or find it impossible to explain them to their audiences.

In an electoral campaign in which the Conservatives have led from the start, there was a natural media tendency to play up any poll hinting at an upset; that is why the YouGov figures which supposedly indicated that the Conservatives may lose their majority received worldwide publicity.

But almost no news outlet bothered to report the fact that YouGov's "shock poll" was not a traditional opinion poll at all; instead, it was a statistical model based on what the company calls "Multi-level Regression and Post-Stratification" analysis, a fancy term for a controversial new technique which works out what one group of voters says and applies it to other groups.

As YouGov chief executive Stephan Shakespeare admitted when releasing his analysis, this was a projection that "allows for a wide range of error". But that did not prevent London's Times daily from splashing the "poll" over its front page, although the paper did point out that the Conservatives "could get as many as 345 seats on a good night… and as few as 274 on a bad night", which was a more polite way of admitting that the figures it was puffing up on its front page were, essentially, meaningless.

Most media outlets also reported that opinion polls were subject to a margin of error. But they invariably failed to tell audiences that this error applies to each party's vote. So, if a poll shows the Conservatives on 40 per cent and their Labour opponents on 34 per cent, the margin of error could mean either that the real situation is one in which the Conservatives are on 43 per cent and Labour on 31 per cent - a 12-point lead for the Conservative government - or that the two parties are running neck and neck at 37 per cent each.

But opinion pollsters also have themselves to blame for being less than forthcoming in admitting a perennial problem - that of getting a representative sample, because it is increasingly difficult to predict voters' turnout.

Actual turnout among voters aged under 25 in Britain is about 30 per cent lower than among voters older than 65, and the young are disproportionately more inclined to vote for the opposition Labour.

It is noticeable that the opinion polls which have predicted a narrower lead for Mrs May are also those which assume that more than 80 per cent of young people will turn out to vote. They may be right in this assumption, but they may also be horribly wrong - turnout is key to this.

However, one thing is certain: Since Britain's pollsters have predicted all possible outcomes, someone will emerge as the industry's winner tonight.

And all others will advance perfectly good excuses as to why their failure to project the outcome will not be repeated next time.