When Covid-19 first hit Europe in February, Dr Angela Merkel, a physicist by education, quickly understood the perils a pandemic with exponential growth could bring.

The German Chancellor managed to swiftly get the heads of the 16 German states on board, and by March, a severe lockdown was already in place. The spread of the virus seemed to be under control, and Germany was hailed for its effective crisis management.

Now, just nine months later, this optimism is gone.

It was Interior Minister Horst Seehofer who conceded the obvious. The advantage Germany had gained on the pandemic in spring has been squandered, he said in an interview this month.

Mr Seehofer, one of the strongmen in the government, made clear that the citizens were not to blame for this failure. "Above all, this is due to insufficient measures," he is quoted as saying.

Last month, Germany went into a light lockdown, hoping this could pre-empt stricter measures and prevent further damage to the economy. This, however, the magazine Der Spiegel now calls nothing less than "possibly the biggest political misjudgment of the year".

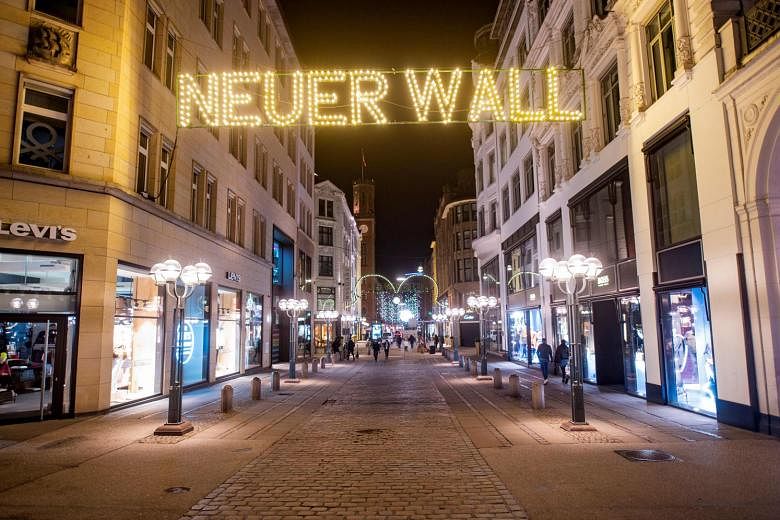

When it became clear that the reduced version of the lockdown had not done the trick, a rigid one went into effect last Wednesday.

In fact, German politics these days is mainly driven by numbers - and they are sobering: Daily new infections have climbed well over 30,000, an increase by one-third compared with a month earlier. Although the death rate, with a total of over 26,000, is still a rather low one in Europe, this indicator is also clearly on the rise.

And the occupancy rate of intensive care beds in hospitals has seen a steep upswing to more than 5,000, almost doubling since early last month. Nursing staff are working at capacity.

During the first lockdown in spring, the wave of infections could be reversed, but this is not happening now. Infection rates are still rising, driving up concerns that at some point, hospitals may not be able to handle all new incoming patients.

A few days ago, one doctor in a hospital in the state of Saxony said that the triage system had to be applied. Triage is used in crisis situations when decisions have to be taken on which patients will receive treatment. The basic values underlying triage decisions include prioritisation of medical urgency, capacity to benefit, fairness, severity of the health condition of the patient and likely outcome.

The doctor's statement produced a public outcry - but also brought to light how severe the situation has become.

The rude awakening in the autumn months of September to November makes the restrictions of summer look like a cakewalk.

Although Dr Merkel was telling the public that the winter months would be much worse, some heads of German states were more concerned about their local businesses and did not heed the warnings.

Since many of the restrictions in Germany have to be implemented at the regional level, the options to act are limited for a chancellor. The federal system is based on persuasion rather than by decree. Dr Merkel has not been able to prevail over local premiers, even those from her own party, the conservative Christian Democratic Union.

Two things have contributed to Dr Merkel's weakness. Since she gave up the chairmanship of the party two years ago, she has lost influence within party structures. A loss of political clout also came when she announced she will not run for another term as chancellor in the 2021 election. She is not a lame duck yet, but her political environment is clearly already focused on a future without her.

And another conflict is already on the horizon: Although BioNTech - a forerunner in developing a vaccine against Covid-19 - is German, it looks as if Germany will not be able to acquire enough doses to get people vaccinated until next summer.

Berlin strictly wanted to toe the line of the European Union and not make use of the home advantage. This means Germany will get the vaccine not earlier than all the other members of the EU, and only according to an allocation key.

But according to a report in Der Spiegel, the EU may not have contracted enough doses, or may have signed agreements with the wrong partners. While the vaccine production of BioNTech-Pfizer is on track, British-Swedish AstraZeneca is in trouble with its test runs, French Sanofi may get the green light only at the end of next year, and CureVac, also German, probably needs another half year until its vaccine is ready.

Germany, which needs up to 120 million doses to vaccinate around 70 per cent of its population twice, now probably has to wait till well into autumn or even winter next year before full immunisation is achieved.

Meanwhile, vaccinations are already under way in Britain and the United States.

The rude awakening in the autumn months of September to November makes the restrictions of summer look like a cakewalk... Since many of the restrictions in Germany have to be implemented at the regional level, the options to act are limited for a chancellor. The federal system is based on persuasion rather than by decree.