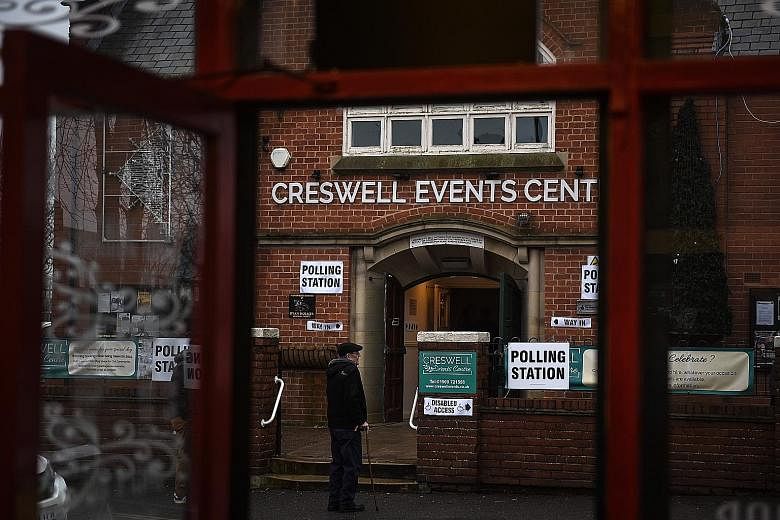

BARLBOROUGH • They trudged through stinging rain to polling stations, streams of people who once powered the left in Britain: former miners, supermarket clerks, retired school teachers and health aides.

But when they re-emerged, they had voted not for the Labour Party, the side that had shepherded them through decades of political upheaval, but for their old nemesis, the party long despised here for shutting down the mines and shrinking the British state: the Conservatives.

"I'm from a Labour background: the coal pits and fighting Maggie Thatcher and everything else," said Ms Dawn Ridsdale, 56, an unemployed sales agent.

She had opposed Brexit, but now wanted someone with the ruthless streak of the prime minister who had closed the mines, Mrs Margaret Thatcher, to sort it out, once and for all.

"The country's on its backside," she said. "I've unfortunately had to vote for Boris. He's the best of a bad bunch."

She meant Prime Minister Boris Johnson, the upper-class eccentric who defied half a century of political geography on Thursday to tear through Labour's old coalition of small-town, working-class voters in the Midlands and north of England.

Down went at least nine seats that Labour had held without interruption since World War II. Down went a type of tribal politics in northern England, in which people inherited voting customs from their parents and grandparents, passing fights over mine closures and benefit cuts down the generations.

And down went Mr Dennis Skinner, the so-called Beast of Bolsover, a former miner and Labour lawmaker whose fusion of socialism and pro-Brexit values had put him in control of Bolsover, the constituency around Barlborough, for 49 years.

For Labour, which suffered its worst election defeat since 1935, the results signalled the end of an era of being able to reach into both thriving cities and left-behind former mining villages for votes.

The party's two wings - pro-and anti-immigrant, young and old, university graduates and tradespeople - were cleaved.

"It's the detachment of the Labour Party from great swathes of the country, which they seem not to sympathise with," said Professor Robert Tombs, a historian at the University of Cambridge. "That leaves the party in a pretty dire position in the long term, unless it can miraculously reinvent itself."

The results in Britain were a sobering lesson on the consequences of destroying age-old party alliances before new ones had time to germinate, analysts said.

"You'll have the pro-migration, culturally liberal left saying, 'We don't want to ally with racists', and you'll have the socially conservative, economically left-wing part of the coalition saying, 'We don't ally with people who think we are racists', and that's a very, very hard argument to resolve," said Professor Rob Ford, an expert of politics at the University of Manchester.

Whether Britons voted for a permanent realignment, or merely one long enough to carry them through Brexit and Mr Jeremy Corbyn's disastrous leadership of Labour, was the big unknown.

NYTIMES