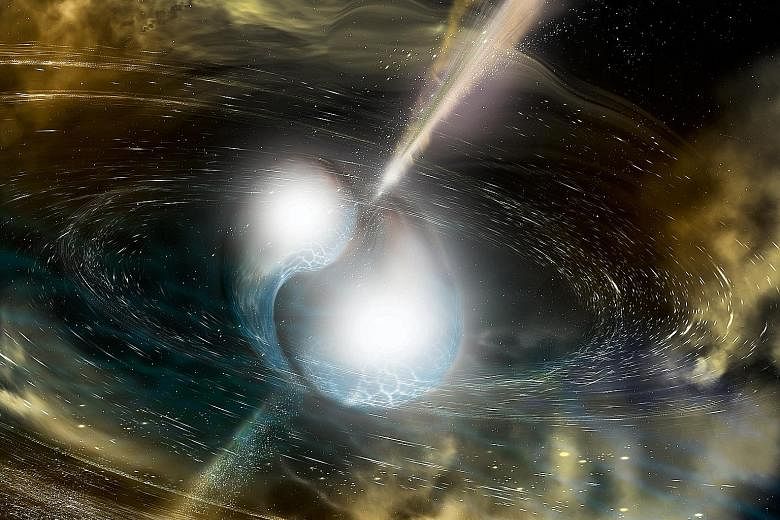

NEW YORK • Astronomers this week announced they had seen and heard a pair of dead stars collide, giving them their first glimpse of the violent process by which most of the gold and silver in the universe was created.

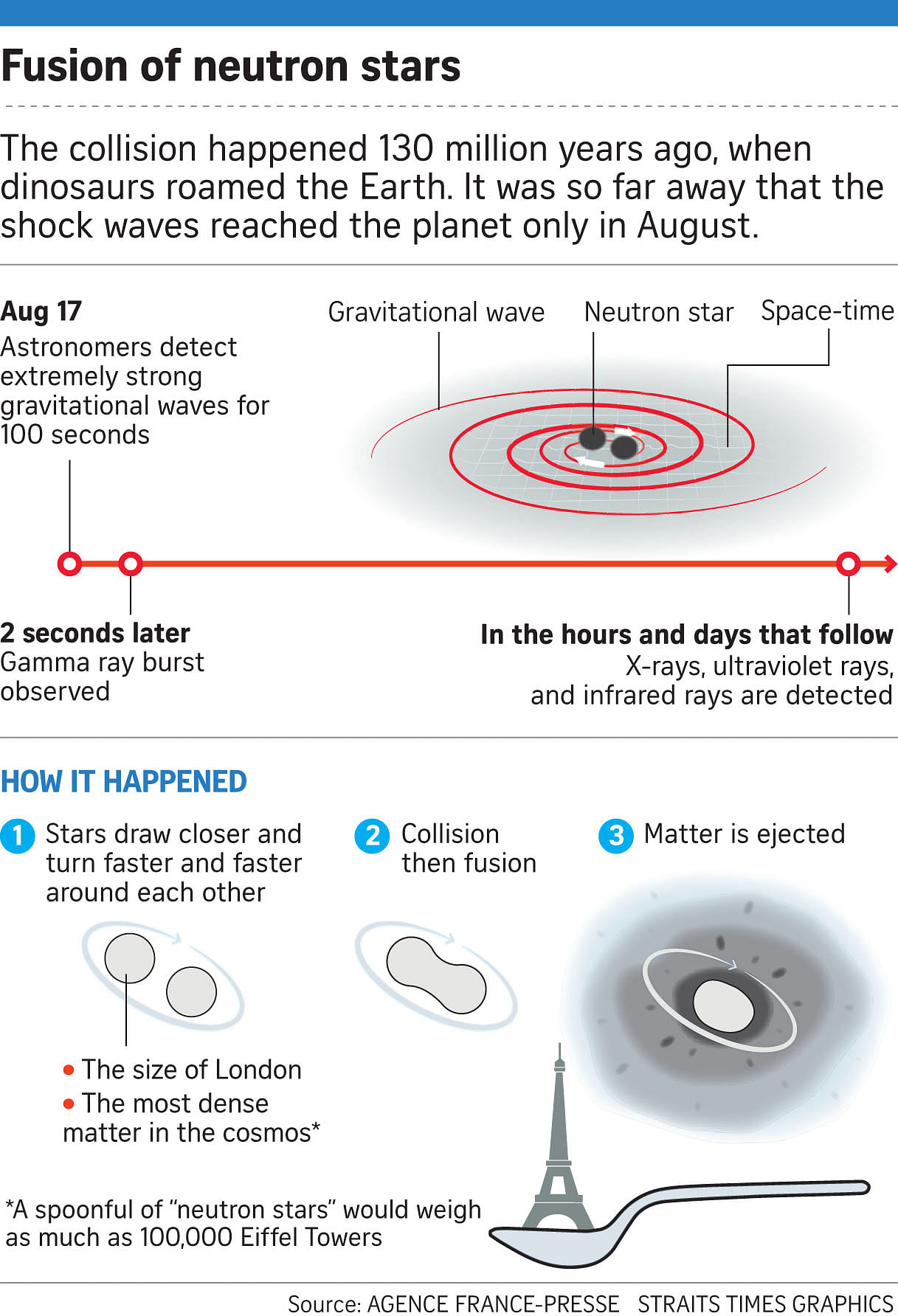

The collision, or kilonova, rattled the galaxy in which it happened 130 million light years from here in the southern constellation of Hydra, and sent fireworks across the universe.

The Aug 17 event set off sensors in space and on Earth, as well as produced a loud chirp in antennas designed to study ripples in the cosmic fabric. It sent astronomers stampeding to their telescopes, in hopes of answering one of the long-sought mysteries of the universe.

Such explosions, astronomers have long suspected, led to many of the heavier elements in the universe, including precious metals like gold, silver and uranium.

It happened when a pair of neutron stars, the shrunken dense cores of stars that have exploded and died, collided at nearly the speed of light. These stars are masses as great as the sun packed into a region the size of Manhattan brimming with magnetic and gravitational fields.

Studying the fireball from this explosion, astronomers have concluded that it had created a cloud of gold dust many times more massive than the Earth, confirming kilonovas as agents of ancient cosmic alchemy.

"For the first time, we have proof," said Northwestern University astronomer Vicky Kalogera.

"It's the greatest fireworks show in the universe," Dr David Reitze, executive director of the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (Ligo) said on Monday.

The key to the find was the detection of gravitational waves, emanating like ripples, vibrating the cosmic fabric, from the distant galaxy. It was a century ago that Albert Einstein predicted that space and time could shake like a bowl of jelly when massive things like black holes moved around.

But such waves were finally confirmed only last year, when Ligo recorded the sound of two giant black holes colliding, causing a sensation that eventually led this month to a Nobel Prize.

For the researchers, this is in some ways an even bigger bonanza than the original discovery. This is the first time they have discovered anything that regular astronomers could see and study.

All of Ligo's previous finds have involved colliding black holes, which are composed of empty tortured space-time - there is nothing for the eye or telescope to see.

But neutron stars are full of stuff - matter packed at the density of Mount Everest in a teaspoon. When they slam together, all kinds of things burst out: gamma rays, X-rays, radio waves.

The discovery filled a chink in the explanation of how the chemistry of the universe evolved from pure hydrogen and helium into today's diverse place. But one burning question is, what happened to the remnant of this collision?

According to the Ligo measurements, it was about as massive as 2.6 suns.

Scientists say for now they are unable to tell whether it collapsed straight into a black hole, formed a fat neutron star that hung around in this universe for a few seconds before vanishing, or remained as a neutron star.

Neutron stars are the densest form of stable matter known. Adding any more mass over a certain limit will cause one to collapse into a black hole, but nobody knows what that limit is. Future observations of more kilonovas could help physicists understand where the line of no return actually is.

NYTIMES