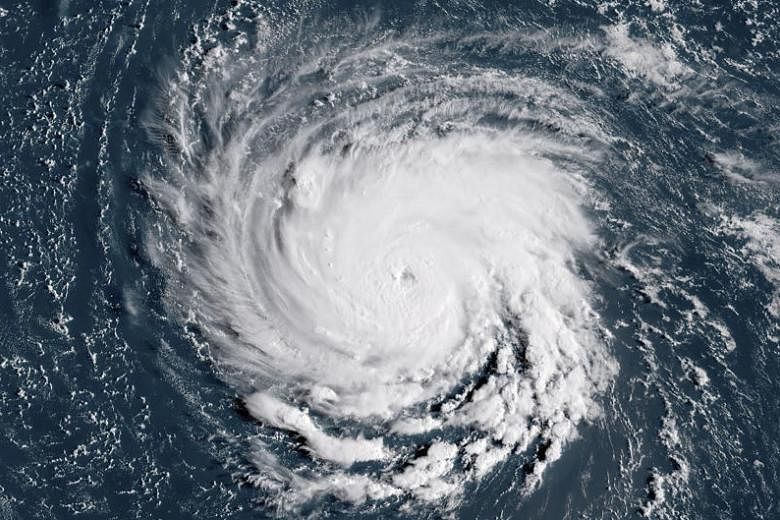

WASHINGTON (WASHINGTON POST) - In little more than a day, Hurricane Florence exploded in strength, jumping from a Category 1 to a Category 4 behemoth with 225 kilometre per hour winds. This process - hurricanes intensifying fast - is both extremely dangerous and poorly understood.

But new research says that as the climate continues to warm, storms will do it faster and more often, and in some extreme cases, grow so powerful that they might arguably be labelled "Category 6".

There is no "Category 6" on the Saffir-Simpson hurricane scale, which goes up to Category 5.

The new science is a testament to the growing ability of supercomputing to power simulations of the planet that show the future of massive features like the atmosphere and oceans, but still also maintain enough detail to capture smaller ones like Category 4 and 5 hurricanes.

That's how a model created at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory generated the new findings, and identified how fast-intensifying storms could make things a whole bunch worse later in this century.

"The reason there are going to be more major hurricanes is not necessarily there are going to be that many more storms ... it's really the fact that those storms are going to get there faster," said Kieran Bhatia, lead author of the new research in the Journal of Climate. Batia completed the work while a graduate researcher at Princeton University and the nearby NOAA laboratory.

We've already seen the signs, in the past several years, of ultra-intense hurricanes that get that way by explosively intensifying. Last year's Hurricane Maria, for instance, spun up from a mere tropical depression into a Category 5 storm in just over two days; or 2015's Hurricane Patricia, whose winds in the Eastern Pacific exceeded 337kph, more than 80kph stronger than the weakest category 5 storms.

Kerry Emanuel, an expert on hurricanes and climate change at MIT, said in an email that the research "may prove a game-changer in climate-hurricane studies." Emanuel was not directly involved in the work.

The study draws on enhanced computer power to achieve something that until now has been very difficult - capturing a reasonable representation of hurricanes in a global climate change model that simulates both the atmosphere and the oceans.

Dividing the globe up into squares roughly 25km by 25km in size, researchers were able to simulate Category 4 and 5 storms, and where they currently occur around the globe - not perfectly, but in a way that was broadly representative.

But when the researchers then moved from simulating the hurricanes of the late 20th century to those of the future under a middle-of-the-road climate change scenario, they found big changes. For the period between 2016-2035, there were more hurricanes in general and 11 per cent more hurricanes of the Category 3, 4 and 5 classes; by the end of the century, there were 20 per cent more of the worst storms.

What's more, the research found that storms of super extreme intensity, with maximum sustained winds above 305kph, also became more common. While it only found nine of these storms in a simulation of the late 20th century climate, it found 32 for the period 2016-2035 and 72 for the period from 2081-2100.

The Category 5 grouping, which is open-ended, begins at 252kph, far lower than the intensities of such storms. And the lower categories require a much smaller increase in wind speeds before reaching the next category. For example, the weakest Category 5 storm would be 38kph stronger than the weakest Category 4.

Recently, some scientists have begun speaking about a possible "Category 6" designation, though there is considerable debate over whether that's really a good idea. Clearly, though, some recent storms would qualify, most notably Patricia but also 2013's Super Typhoon Haiyan and several others.

"It's what you expect if you have a shift toward more intense storms, is that you'll start seeing intensities you haven't seen before," said Gabriel Vecchi, an atmospheric scientist at Princeton who was one of the study's authors.

That said, Vecchi isn't sure about the "Category 6" concept. "I think I'd bring a social scientist in here to see what the net value of having a Category 6 designation would be," he said.

Perhaps most significantly, the new research finds that rapid intensification appears to be the key mechanism driving stronger storms in a warmer climate. Sure enough, in future years it finds more storms that strengthen by more than 72kph in 24 hours, as Hurricane Florence did, and even a number of rare and super-extreme storms that intensify by more than 185kph in 24 hours.

To understand why rapid intensification matters, consider the globe's current population of tropical cyclones (which are variously termed hurricanes, typhoons and just cyclones, depending on the region). There are many relatively weak ones - Category 1 and 2 - but also many dangerous and intense storms with winds that exceed 210kph.

The difference between the two groups, prior research has found, is often a difficult-to-forecast process in which the hurricane rapidly strengthens, usually in the presence of highly favourable environmental conditions, such as extra warm seas to considerable depths, lots of available humidity in the air and slack winds around the storm.

Because warmer ocean conditions are exactly what climate change is expected to produce, it has been natural to wonder whether more fast-intensifying storms will be in the offing. Now, the new research has suggested that this will indeed be the case.

Granted, the forward-looking study by Bhatia and his colleagues remains agnostic about precisely what is happening right now - a period in which we are already seeing very strong storms, such as Patricia.

"This paper doesn't really say what we've had so far, if there's a trend," said Bhatia. "It literally just says, 'Okay, in this particular model, climate change is going to make XYZ more likely.'

"But that model is a major advance, said MIT's Emanuel, who was not involved in the research but says he is "quite familiar" with the study.

The new computer model's resolution is "one of the highest yet achieved" for a global climate model that captures the entire Earth and both its atmosphere and oceans, said Emanuel in an email. "It is important to note that this still under-resolves (tropical cyclones), but it is an important step in the right direction. Unlike almost all other (global climate model)-based studies, it simulates Cat 4-5 storm and it projects an increase in the overall frequency of (tropical cyclones) globally."

But another top hurricane researcher, Chris Landsea, who directs the Tropical Analysis and Forecast Branch of the National Hurricane Center, was less convinced, noting that the study's large projected increases in the strength of future hurricanes "deviates from most of the earlier published work which showed ... no significant change in major hurricane numbers, and only a 2-5 per cent increase in intensity of hurricanes."

Scientists have been debating precisely what is happening to hurricanes as the climate warms for well over a decade; no one study will change that, as its authors themselves acknowledge.

Meanwhile, as scientists continue their debate, Hurricane Florence is set to cross seas a degree or more warmer than normal on its path to the US east coast.