Sporting minnows also need bold vision

88 years after its first medal, South-east Asia is still striving to make a sporting name for itself

The cynic could tell them, the shooter and the jumper, that they have little chance. He might laugh at them and say they're too small. He may selectively pick a statistic and sneer that there are 600 million from 11 nations in South-east Asia and not one won a gold at the 2012 Olympics.

But athletes are optimists and they aren't listening. In the Philippines, the weightlifting daughter of a motorised rickshaw driver hikes up mountain trails. In Indonesia, a girl born with smaller lungs makes big leaps in a long-jump pit. In Vietnam, a fine shooter makes do with a small quota of pellets.

They all speak different languages but they share a common geography and carry a joint dream. They come from a South-east Asian clan and they are going to join the tribe of Olympians. They travel in search of medals and memories, relevance and validation. They are the Olympic heirs to Indonesia's Susi Susanti, who won badminton gold in 1992, and proof that their lesser-known nations also matter at this Games.

They go as our ambassadors to introduce our nations to those who skipped map studies. SIN, people ask, where is that? VIE, what's that nation? Strangers hear our anthems and wonder where we're from. And so these are not just athletes we send to Rio, they are geography teachers in short pants. We're trying to beat the world and educate them at the same time.

When we win, people get to know us a little. As Susanti told the New York Times in 1992: "When Alan (Budikusuma, her then-fiance) and I got gold medals in singles in Barcelona, the world knew Indonesia better." When we win, people inadvertently learn about our history. When Thailand's Somluck Kamsing won the featherweight boxing gold in 1996, he held up a picture of his king.

Historically it hasn't been easy for us to win because sport isn't coded into our culture. We're not naturally sporty nor often the right size. We come from nations often bereft of high-class sporting infrastructure and rarely spend our weekends in the colours of a local team.

We're rich in monuments but in many places we're still beset by hardship. In 2011, the Philippines, with a population of roughly 100 million, spent $27.6 million on sports; in Australia, with just over a quarter of that population, A$325 million (S$330 million) was allocated to sports programmes in 2010. Our priorities are different: We want degrees in law for our kids but we're nervous about baccalaureates of the boxing ring.

In a lopsided world we're scrapping with nations with hefty budgets and sleek sports science centres and it's like competing against a swimmer with flipper-sized feet. The top five nations at the 2012 Games earned 148 gold medals, the next 49 countries won just over 150.

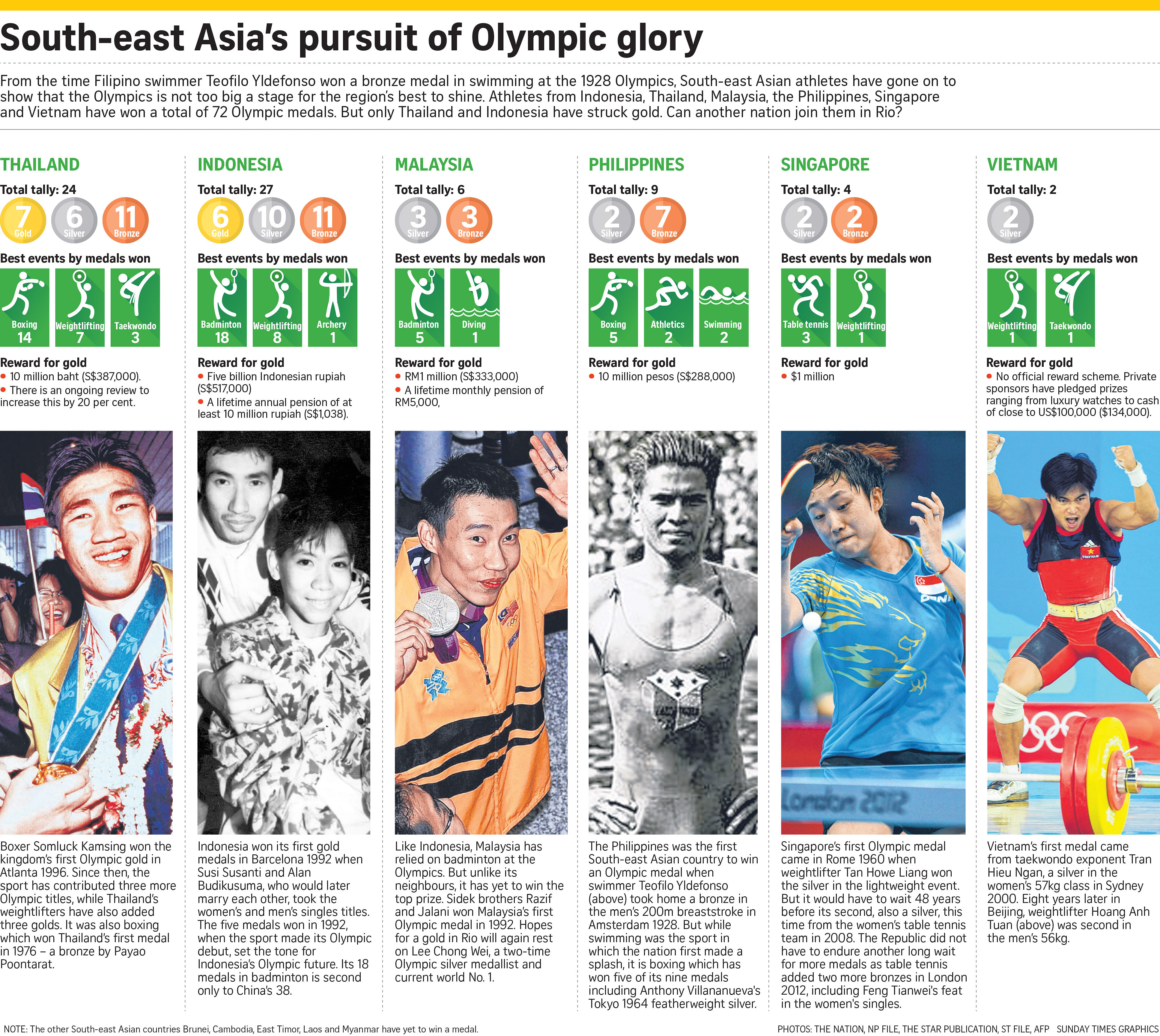

And yet, as a region, we do win medals, we do have a history, we are improving, we do matter. Indonesia has 27 Olympic medals, Thailand has 24, Vietnam has two, the Philippines has nine, Malaysia has six, Singapore has four. We've won them in boxing and weightlifting, taekwondo and table tennis, badminton and archery, athletics and swimming. We've proved that victory is no nation's birthright. Sure, rich countries come armed with chefs and chiropractors and dressed in Ralph Lauren outfits but talent from everywhere has a place in these Games.

Pandelela Rinong's father was a contract worker, yet he drove her to diving classes on a motorcycle and then in 2012 she, a Malaysian girl, won Olympic bronze. This year Ratchanok Intanon, the 2013 badminton world champion whose mother is a Thai factory worker, will chase gold while Joseph Schooling, a boy from tiny Singapore, will attempt to challenge Michael Phelps, whose nation has won more than 500 Olympic swimming medals.

They come to the Olympics because it is where athletes want to measure themselves. But their job will be harder if South-east Asian officials stay stuck in a regional rut.

To pick the odd indigenous sports for the SEA Games is to pay homage to our cultures; to pick a slew of them in the pursuit of medals is short-sighted. That we even had a debate over whether the marathon should be included at the next SEA Games in Malaysia is awkward thinking. We must have Olympic-sized dreams for how else do we teach our athletes not to be fearful?

Fortunately for all the obstacles before us, we still produce athletes who do not think small or scared. More than 80 years ago, a swimmer from the Philippines who trained in a river and had no coach won bronze in the 200m breaststroke at the 1928 and 1932 Olympics.

Teofilo Yldefonso is in the International Swimming Hall of Fame, which states in its profile of him that "by bringing the stroke more to the surface of the water rather than under the water as was more common at that time", he was referred to in European textbooks as "The Father of the Modern Breaststroke".

Yldefonso fought against the Japanese in World War II, was captured and endured the Bataan Death March. His profile states that Yoshi Tsuruta, Japan's gold medallist in the 200m breaststroke in 1928 and 1932 and later an army officer, heard about his friend Yldefonso's imprisonment and "called for his release". It was too late.

One report says Yldefonso's remains were never found; another says he died in his brother's arms. It is a story worth telling because as South-east Asian athletes ready for Rio, they must know of the first multi-medallist from their region and the gallant footsteps in which they must walk. As they go to make history they must know their history.

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

A version of this article appeared in the print edition of The Sunday Times on July 31, 2016, with the headline Sporting minnows also need bold vision. Subscribe