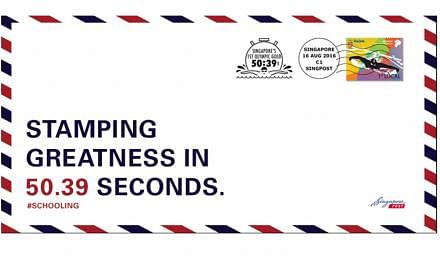

One hundred metres. That's all it takes? To rewrite history. Launch a revolution. Glue a nation. Fifty point three nine seconds. That's all it requires? To lift a mood. To give proof of excellence. To alter a life. One man with a butterfly touch can do all this? Yes, Joseph Schooling can.

Except it hasn't taken only a hundred competitive metres but millions of practice metres. Except it hasn't taken one victory to get there but also a thousand awful failures. Except it hasn't taken 50.39 seconds but 15 years of hurting and wanting. Change comes suddenly for us, but for the swimmer it is built from a life of perseverance. A generation of greats cannot be tamed overnight.

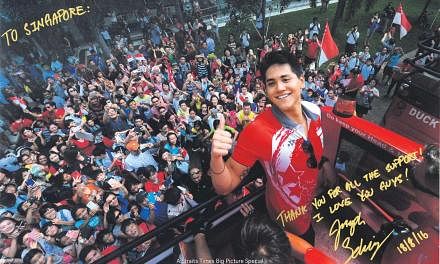

Joseph Schooling is going to inspire Singapore, but no one can ever imitate him. He's the first to come first. Every Singaporean Olympian from now on will only follow him. In a lovely irony, the only place he is last is onto the podium in Rio.

There they gathered, the butterfly men. Three silver medallists, Michael Phelps, Chad le Clos, Laszlo Cseh, together on one level. Schooling, his name announced last, alone and higher. He is only starting to discover that it is beautifully lonely at the top.

The bronze medallist's spot is empty, just open space, like what there is behind Schooling at the finish of the final. In 2004 at Athens, the gap between first place and second is .04 of a second; in 2008 it is .01, in 2012 it is .23, here it is a massive .75. At the mixed zone, le Clos will sum up Schooling's time in two admiring words: "Crazy quick."

This kid - he's 21, Phelps 31, Cseh 30, le Clos 24 - has style. He doesn't just win his first final, he ends a 100m race after 60m. "After the turn and three strokes, no one was going to catch him," says Sergio Lopez, the coach who made him. This kid - face like a choirboy, ambition like a streetfighter - has panache. He grows up worshipping a liquid god who hasn't lost a major 100m butterfly race since 2005 and then he drowns his deity's dream.

In Greek mythology, Nereus was the old man of the sea. His father was the Sea, his mother the Earth. In modern times, his equivalent is Phelps, 31, the great old man of the pool. He lives on Land, he ruled the Water. He's won more individual golds than Leonidas of Rhodes did at the Ancient Olympics in 152 BC and hasn't lost a race all week in August 2016.

Till a boy born in Bedok, who starts swimming and dreaming because of Phelps, will eventually out-swim Phelps. What cheek, what courage, what perfection.

Just after 10pm in Rio, Phelps and Schooling meet on the pool deck like ancient duellists: American in black cloak, Singaporean in red. The crowd rises for Phelps, later they will stand for Schooling. Up in the stands, May Schooling is nervous. A Dutch spectator hears she is the mother of the challenger and produces a vuvuzela from a bag and blows it. The swimmers are off.

Joseph swims, May pleads. Anxiety has reduced her to her usual one-word race vocabulary: "Go, go, go, go, go." Joseph listens to his mother. Go, he does.

The race is not making sense: By the end, you expect Phelps, even if tired, to go faster, except Schooling will not go slower. He hits the wall first and May manages to find another word. "Ecstatic." A Singapore flag waves in her hand and a phone, which she's too scared to open, is buzzing wildly in her hand. A stranger asks, "the mama?" and takes a wefie with her.

All those years she - and her husband, Colin - travelled to America when Joseph was in school there, cooking, caring, believing, trusting, doing all that invisible stuff that parents do, and now look at what her boy has gone and done? He's changed her world, his world, our world. Every Singaporean at the Rio pool looks a little dazed, as if they've seen a miracle and are unsure if it is real.

Downstairs, Quah Zheng Wen, the talented butterflier stands quietly. "It's pretty amazing seeing our flag out there. It's something else. I'm proud about how far we have come, especially Joe." Standing a few feet from him is Lopez, in Singaporean red, a bulky, heavy man, who looks like he's escaped from a wrestling ring, and now he is crying.

This Schooling, he's shaking everyone's world. This Schooling, for this night, it is his world. Three of the greatest butterfliers, all older, are paying homage to him. "I'm proud of Joe," says Phelps and because the American is a competitor, the ultimate racer, part of him will admire Schooling for not confusing respect with mercy during the race. In sport, the finest compliment to your idol is to beat him and show him how fully you have been inspired.

Phelps, who comes in late for the press conference, is generous. He tells reporters who hurl questions at him, hey, the "kid just won a gold, ask him some questions". He says he's "excited to see how much faster (Schooling) goes". Schooling in return is deferential: "One gold medal is nuts; I can't imagine 22 or 23."

After a week of fractiousness at the pool, this is a fine change: A hard race, then a respectful aftermath. The king classy, the kid courteous. You can't say a baton has been passed because Phelps' 22-gold baton should be kept in a museum. But a calendar is changing. It's now finally 2016 AP. After Phelps.

Phelps dared Schooling to dream and he did, and now Schooling dares us. He, and his parents, and coach, have demonstrated what is possible if you take risks, show commitment, make an investment, and keep the faith. Second best was never their ambition. We would have been happy with any colour of medal, but he only wanted gold. Now proof of his unwavering belief and labour is hanging from a ribbon round his neck.

Schooling worked all his life for gold, but wearing gold is not easy. It's almost unnerving to be an Olympic champion, it's dazzling, it's difficult to digest that you're the best in the world. Le Clos, wearing a smile, says at the mixed zone that he's waiting for the world championships next year, waiting for Schooling. If you chase the world and win, it chases you. But if Schooling ever needs advice in being pursued, he can always call the retiring Phelps.

Fittingly, an evening that began on the pool deck with the American and Singaporean, ended the same way. Medals awarded, both men walked past adoring crowds and clicking cameramen, lost in amiable chatter. Schooling is not quite Phelps' equal, and yet on this night, he was his conqueror. The 100m butterfly was over and they walked together into new lives: one the greatest champion, the other the latest.