This story was first published in The Straits Times on May 1, 2010

SINGAPORE - His English is impeccable, his accent clipped, his memory razor sharp, and he is modest and polite to a fault.

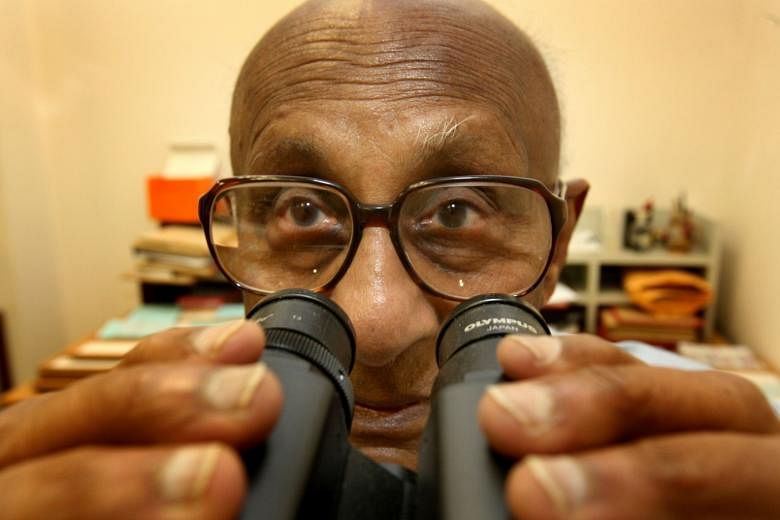

Oozing old world charm, Professor K. Shanmugaratnam is one very sprightly octogenarian.

'I have to thank specialists in the department of dentistry, orthopaedics and urology who have kept me in good condition. And my cardiologist colleagues who have kept me alive,' he quips, adding that he has three stents in his heart, the last of which was implanted just two years ago.

The occasional health hiccup has not come between him and his work. Prof Shanmugaratnam is in his National University Hospital office promptly at 7.30am, Mondays to Fridays. He puts in eight-hour days as a consultant histopathologist, specialising in the microscopic examination of diseased tissue. He works mostly on difficult cases referred to him by clinical specialists and other pathologists.

Several times a month, he also conducts teaching sessions or seminars for trainee pathologists and organises departmental case conferences.

The father of three, one of whom is Finance Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam, and grandfather of four says he will continue working 'as long as I am able, as long as I am needed and as long as I have nothing better to do'.

'And this is what I do best. I am happy when problematic cases are diagnosed correctly and especially when histological diagnoses lead to successful treatment,' says Prof Shanmugaratnam who was awarded the Public Administration Gold Medal in 1976 and conferred the title of Emeritus Professor by the University of Singapore in 1986 for his achievements in pathology. In 1996 he was awarded the title of Distinguished Fellow by the Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia.

One of five children of a teacher and a homemaker, he entered the College of Medicine in 1937.

His interest in pathology was piqued when the Japanese Occupation interrupted his studies, and he went to work as a medical laboratory technician in the Japanese Military Hospital as well as in the pathology department of what is now KK Women's and Children's Hospital. It was then known as the Central Civilian Hospital, and was called Chuo Byoin during the war.

When he graduated after the war, he joined the Singapore Government Medical Service as an assistant pathologist.

Over the years, he held many positions, including senior pathologist for the Ministry of Health, and also professor and head of the department of pathology at the University of Singapore. He was appointed Emeritus Consultant by NUH in 2005.

Prof Shanmugaratnam, who has a PhD in pathology from the University of London, has also served in many international bodies. He was, among other things, president of the International Council of Societies of Pathology (1974-1978), president of the International Association of Cancer Registries (1984-1988) and head of the International Reference Centre for the Histological Classification of Tumours of the Upper Respiratory Tract (1972-1995).

One of his most significant contributions was setting up the Singapore Cancer Registry. It began as a modest pathology-based register in 1950 when he was with the Singapore Medical Service.

He recalls: 'I was interested in it because the department of pathology was involved in a major part of the diagnostic work.'

In 1968, when he was working with the then University of Singapore, the Singapore Cancer Registry became a comprehensive registry for all cancer cases in the country, regardless of means of diagnosis.

'To get an idea of the size of the pro-blem that cancer was, there has to be an accurate epidemiological evaluation, you have to count all the cases,' says the professor who was the registry's director from 1968 to 2002.

This was before the age of computers so data had to be manually collected from several sources.

Singapore, he says, is a very suitable place for a population-based registry.

'It's very hard to find incidences of this or that cancer in populations with a lot of movement. But this is a small country with a well counted population, very good medical services, and we had the only pathology department then serving the whole island.

A population-based registry, he adds, could provide reliable data as well as trends and pattern in cancer occurence.

Transferred to the Ministry of Health in 2001, the registry now comes under the Health Promotion Board.

Prof Shanmugaratnam says much has changed in the practice of pathology over the years. 'Fifty years ago, a histopathologist dealing with a tumour specimen was required to provide little more than a brief description of its microscopic feature and to give a diagnosis based on the technology then available.

'Today, they are expected to give detailed descriptions including features which may influence prognosis or response to treatment.

'They have to identify the tumour more precisely, using immunohistologic, hybridisation and molecular techniques when necessary; they also participate in meetings of tumour boards that plan clinical management.'

Medical teaching has also changed.

He recalls: 'When I began teaching in the College of Medicine, we did not have the computers and PowerPoint technology that we now take for granted. The department of pathology did not even have a camera or a slide projector. We used blackboard and chalk. There are, however, some basics in medical education that technology has not changed.

'There are operational skills that have to be learnt through experience and actual practice. And there are lessons on behaviour that are most effectively taught by setting an example.'

He reads regularly to keep himself up-to-date on trends in pathology and medicine. He also enjoys reading local history, as well as listening to classical music.

To keep fit, the former college cricket captain takes half-hour walks two or three times a week.

Prof Shanmugaratnam's dedication to his work has earned him the respect of many medical professionals. Prof John Wong, 52, who is dean of the National University of Singapore's Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, describes him as a 'living legend'.

The good professor shakes his head and protests bashfully: 'No, no, no. I'm nothing remarkable, nothing remarkable.'