AS A member of the Museum Roundtable, the Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research took part in International Museum Day 2009, a worldwide event to raise public awareness of the importance of museums in national development.

On May 24, the museum opened its doors, only to be greeted by a huge crowd patiently waiting to be admitted. It was estimated that some 3,000 people showed up on that day. The response was overwhelming and the staff was completely exhausted but exhilarated by the response. This set off a giddy chain of events that would eventually culminate in the decision to establish Singapore's own natural history museum.

The first salvo was fired by Jaya Kumar Narayanan, a member of the public, who wrote to The Straits Times Forum Page highlighting the lack of space and the inaccessibility of the museum's location.

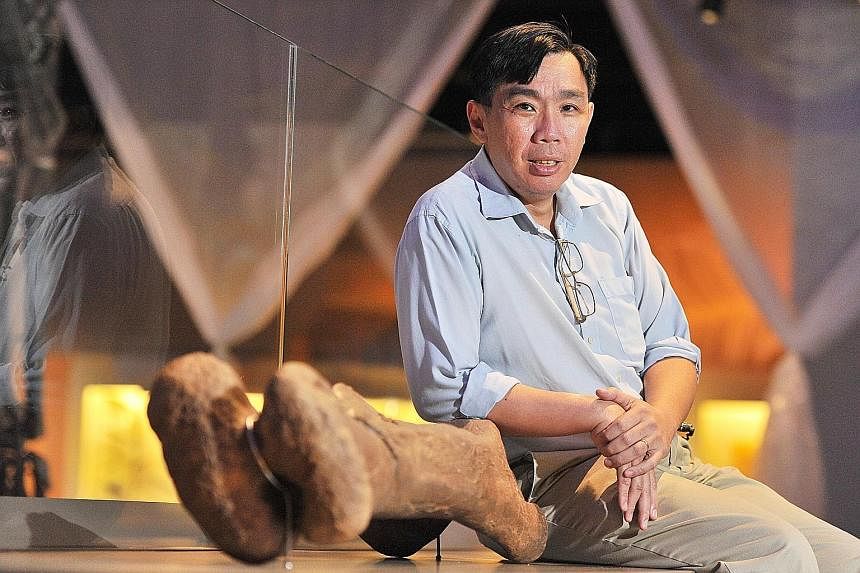

Victoria Vaughan of The Straits Times followed up with an article highlighting the museum's predicament, in which she urged (director of the Raffles Museum) Peter Ng to speak bluntly. In response, Ng made an open call for a permanent natural history museum to be built, saying: "We have an art museum, a civilisation museum, a heritage museum, but natural history is lodged in a corner of the university where no one can find it."

Ng also revealed that over the last four years (2004-8), he had been holding informal talks on the possibility of setting up a natural history museum with the Singapore Zoological Gardens, the Singapore Science Centre and the National Parks Board but "the zoo's commercial interest and the centre's

education focus were thought to be in conflict with the RMBR's research agenda, and NParks already has its work cut out looking after plant specimens".

Ten days later, on June 14, 2009, Tan Dawn Wei wrote a very influential full-page article in The Sunday Times openly appealing: "Let's have a natural history museum for Singapore."

Ng recalled: "(We) were inundated with visitors - thousands of people crowding into a 200 sq m gallery sited behind a small building deep in the bowels of NUS. The visitors growled - tough to find, hard to get to, gallery too small, too little displayed - complaints galore. But there was one common denominator - they all loved the place and echoed Tommy Koh's hope: Bring back Singapore's natural history museum!"

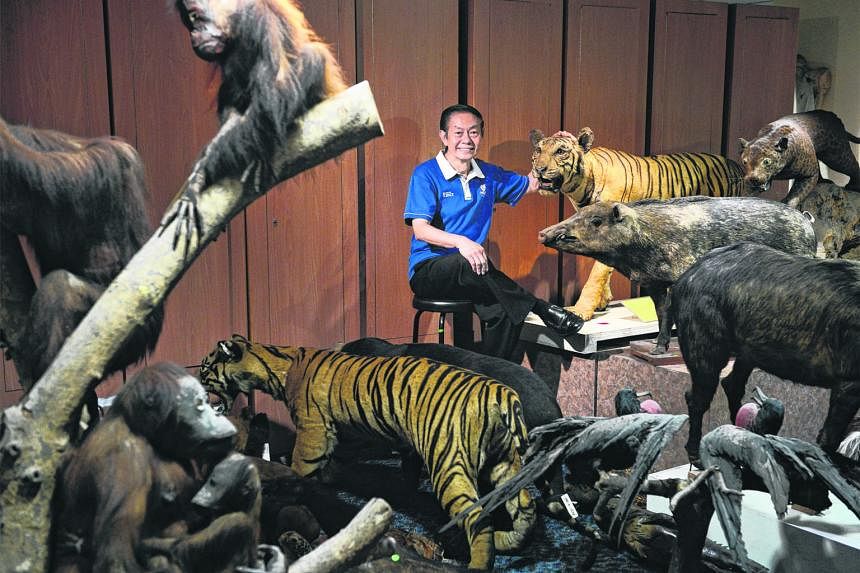

A few months before the fateful Museum Day, Professor Leo Tan Wee Hin had returned to the university. He would eventually be a key player in the efforts to establish Singapore's natural history museum.

Born on Oct 19, 1944 in Singapore, Tan was educated at St Joseph's Institution and then at the University of Singapore where he obtained a BSc (Hons) in Zoology. He was awarded a research scholarship and became the first local person to do a doctorate in Marine Biology. He joined the University of Singapore as a Senior Tutor in 1973 and taught at the Zoology Department from 1973 to 1986 where he rose through the ranks to become Senior Lecturer.

In 1982, he was seconded to the Singapore Science Centre as its Director while concurrently teaching at the university. He left the university in 1986 to become the centre's full-time Director and remained there till 1991. During his directorship, he developed the Science Centre into one of the world's best science museums. In 1991, Tan became Foundation Dean of the School of Science at the newly formed National Institute of Education (NIE).

Three years later, he became Director of NIE and remained there till 2008 when he returned to the National University of Singapore as Professor and Director of Special Projects Dean's Office in the Faculty of Science.

Recalling the sequence of events, Tan stated: "We had joined the Museum Roundtable and it was publicised. We tried twice before, but on that day, 3,000 people turned up and the papers were intrigued and wrote a report on that. And two weeks later, on the 14th of June, Tan Dawn Wei from Straits Times wrote a huge piece in The Sunday Times entitled, 'Let's have a natural history museum'. I read it and I said, 'Wow!' Prior to that, several people (had written in) to the Forum Page saying it (was) a good idea. 'Why is it that we don't have a natural history museum?'"

The mystery donor

THE newspaper articles and the public's positive response delighted the museum but were not in themselves sufficient to establish a full-fledged natural history museum. Ng had - following his study tour of the best-run natural history museums in the world - identified three key ingredients for a natural history museum: good governance, a healthy endowment, and a dinosaur.

The Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research was certainly well-governed, but it had no endowment and it certainly had no dinosaur.

Unbeknownst to the team at the museum, they were to acquire all these ingredients over the next five years. A week after Tan Dawn Wei's article was published, "a pleasant, nondescript gentleman turned up" and spoke to Tan Swee Hee (b. 1971), a research officer at the museum, wanting to learn more about the museum. Tan brought this to the attention of his boss, Ng.

This gentleman was a rather mysterious person who only initially left a mobile contact number, and wanted to be known only as "James". Ng had several more meetings with James, who later said that he represented a group of anonymous donors and that they might be able to start the ball rolling in the fund-raising efforts for the museum. Eventually, James told Ng that the donors were prepared to give the university $10 million to build the museum. Ng was dumbfounded but worried since everything was all so mysterious, but James assured him that there would be no doubt as to the donors' genuineness and sincerity when all final arrangements were made.

True to his word, the senior lawyer named by James as the anonymous donors' representative was a well-known alumnus and adjunct staff of the university. Baffled, Ng conferred with Leo Tan - who had just returned to the Science Faculty. For Tan, the donors were an important "sign" that it was time to finally pitch for the building of a natural history museum.

As a schoolboy, he had visited the old Raffles Museum many times and marvelled at its exhibits; as a young doctoral student, he spent many hours researching the Zoological Reference Collection and solemnly promised himself, "If I could, one day, I'd like to restore the old Raffles Museum." At that point, Tan saw the donors' offer as a chance for him to help "return the collection to the people of Singapore".

With an offer of $10 million, Tan was confident that a new museum was within striking distance. He had seen how the Dentistry Faculty building - which was mainly pre-fabricated - had been built for $17 million and surmised that that was all that was needed.

Ng and Tan decided to approach the university's president, Tan Chorh Chuan, for advice on the matter. "That will do," he thought, as he went with Ng to meet the president.

"So we went to Chorh Chuan and we said, we can do it for $20 million. Assuming we have this $10 million, we need to only raise another $10 million. Do we have your permission to commence fund-raising?"

The president's eventual reply stunned Tan and Ng. After consulting with the university's building and estates people, he told them that $10 million was not enough. They would need at least $25 million to $30 million to build a respectable building. Tan and Ng would therefore need to raise another $25 million. The president added that he believed the museum to be a very worthwhile project and that he was prepared to set aside a piece of land at the soon-to-be-built University Town for it. However, he also let them know that he simply could not reserve that piece of land for them indefinitely.

He gave the pair six months to raise the money. This timeline was imposed as the president could not hold onto the land any longer without giving due consideration to other demands on the space by other sectors of the university. They accepted the terms and staggered out of the president's office around 7pm that evening.

Over dinner, they stared at each other and asked themselves, "What have we just promised?" Tan recalled: "We were just two scientists, who knew nothing about business or fund-raising, and here we were, having just committed to raising $35 million by the following June!"

One particularly attractive aspect of this daunting fund-raising endeavour - at least insofar as the university was concerned - was that the Singapore Government would match, dollar for dollar, all funds raised. This matching scheme would enable the university to build up its endowment fund that could be invested to generate core funding for the university's various institutions.

Race against time

IN HIS own inimitable and indomitable way, Tan set out to raise the remaining $25 million from various foundations, organisations and the public. It was a desperate race against time. To raise that much money so quickly, they needed as much publicity as possible. They approached Singapore Press Holdings, which offered them a $5,000 donation but undertook to give the proposed museum the much-needed publicity.

Tan recalled: "It was a race against time, but the best part about it was that while we only got $5,000 in donation from Singapore Press Holdings, their reports, both Straits Times and Lianhe Zaobao... every month they gave us one story. And I said, 'Money can't buy that kind of publicity.' So I'm very grateful to SPH. They gave us the best kind of publicity we needed."

By February 2010, they had raised only about $750,000. They needed a miracle. Over the next few months, they spoke to everyone they could think of. In April, Tan and Ng started their public campaign by each pledging $20,000 towards the project. Their personal contribution was significant and important for, as Tan recalled, they needed "the moral authority" to raise money from the public, and their personal commitment meant that they would not "feel ashamed to beg".

They wrote 700 letters to friends and acquaintances asking them to donate to the cause. An external fund-raising consultant told Tan that this kind of "spray and pray" strategy was foolish and often yielded very poor results.

The final response, however, was overwhelming: "We started this in April, two months before the deadline. The public came in with almost a million dollars. We wrote over 700 letters, two pages each. We wrote from the heart to all the people and organisations we knew. We got back 400 replies with donations... $1, $6... we accepted any amount. It was a simple letter.

"One secretary gave us half a month of her salary, and another one gave me her whole month's salary. Another technician gave $20,000 outright without even blinking. Amazing. When people put their money where their mouths are, they believe in this cause.

"I told Peter we had to press on. Whether we got the money or not, whether it was enough or not, we have to go ahead with it, and raised almost $1 million from the public."

10 minutes for $10 million

WITH $10 million from the anonymous donor and just under $1 million from the public, Tan and Ng were still short of $24 million and were in a bit of a quandary as the university's Development Office had already been trying to raise funds from all the major foundations for the University Town project. Tan, whose network ranged far and wide, approached every notable he knew - ministers, businessmen, and even the President of Singapore. Another institution Ng and Tan approached was the Singapore Totalisator Board (Tote Board) but they were told that the organisation did not support scientific infrastructure or museums per se. They were aware that it was a long shot, as Ng recalled:

"We had more discussions explaining that it was not just science but our national natural heritage... And we were lucky that the board's chairman at that time, Bobby Chin, was a passionate believer in natural heritage. We eventually submitted a proposal for a heritage museum to Tote Board and were delighted that it was shortlisted."

After that, Ng was told that he had exactly 10 minutes to present and convince the Board to give the university the money for the museum. He prepared a very punchy and sharp set of slides and did his presentation within the allotted time - what Ng loved to call his "10 minutes for $10 million" speech - and was greeted with just a few polite questions.

A few days later, the Board replied: Ng and Tan could add another $10 million to the fund.

'Make it world-class'

THE next $15 million came through the Lee Foundation. Tan had, at a private function, mentioned their fund-raising efforts to Dr Lee Seng Tee (b. 1923), the second son of the legendary philanthropist, Lee Kong Chian. Dr Lee invited Tan and Ng to the Lee Foundation office at the OCBC Building and asked for more details about the project.

It did not take long for them to convince him of the importance of the museum and its immense heritage value for the country. Shortly after, the Lee Foundation pledged $15 million to the project.

Pleased, Ng and Tan pressed on with their fund-raising endeavours but were not very successful for quite some time. Some weeks before the six-month deadline, both Ng and Tan received an urgent call from the Lee Foundation, saying that Dr Lee would like to meet up with them again. This got them both very worried.

Why would he call them at such short notice? Ng recalled: "What now? Was it going to be bad news? We walked in there and talked to him. It was very surreal. Dr Lee looked at us and said, 'We gave you $15 million.' We said, 'Yes, thank you very much.' Then he said, 'Is $15 million enough to make it world-class? I tell you what, we'll round it up to $25 million. Make it world-class, OK?'

"What was there to say? It was a very short meeting and as we walked out, I looked at Leo and asked, 'Leo, what just happened?' For the first time, I actually saw Leo looking a bit stunned."

When June came around, Tan and Ng had done "the impossible". They had raised $46 million for the museum in the immediate aftermath of the global financial meltdown of 2008.

In addition to the three big donors, who had contributed a total of $45 million towards the building of the new museum, the rest was made up of public donations.

With this, the university was assured of the substantial matching grant from the Singapore Government. Typically, all endowment monies went into the university's central pool, but the university president made the bold move of agreeing to allow the matching funds to be tied to the museum so that it could build up an independent endowment that would take care of part of the museum's operational costs.

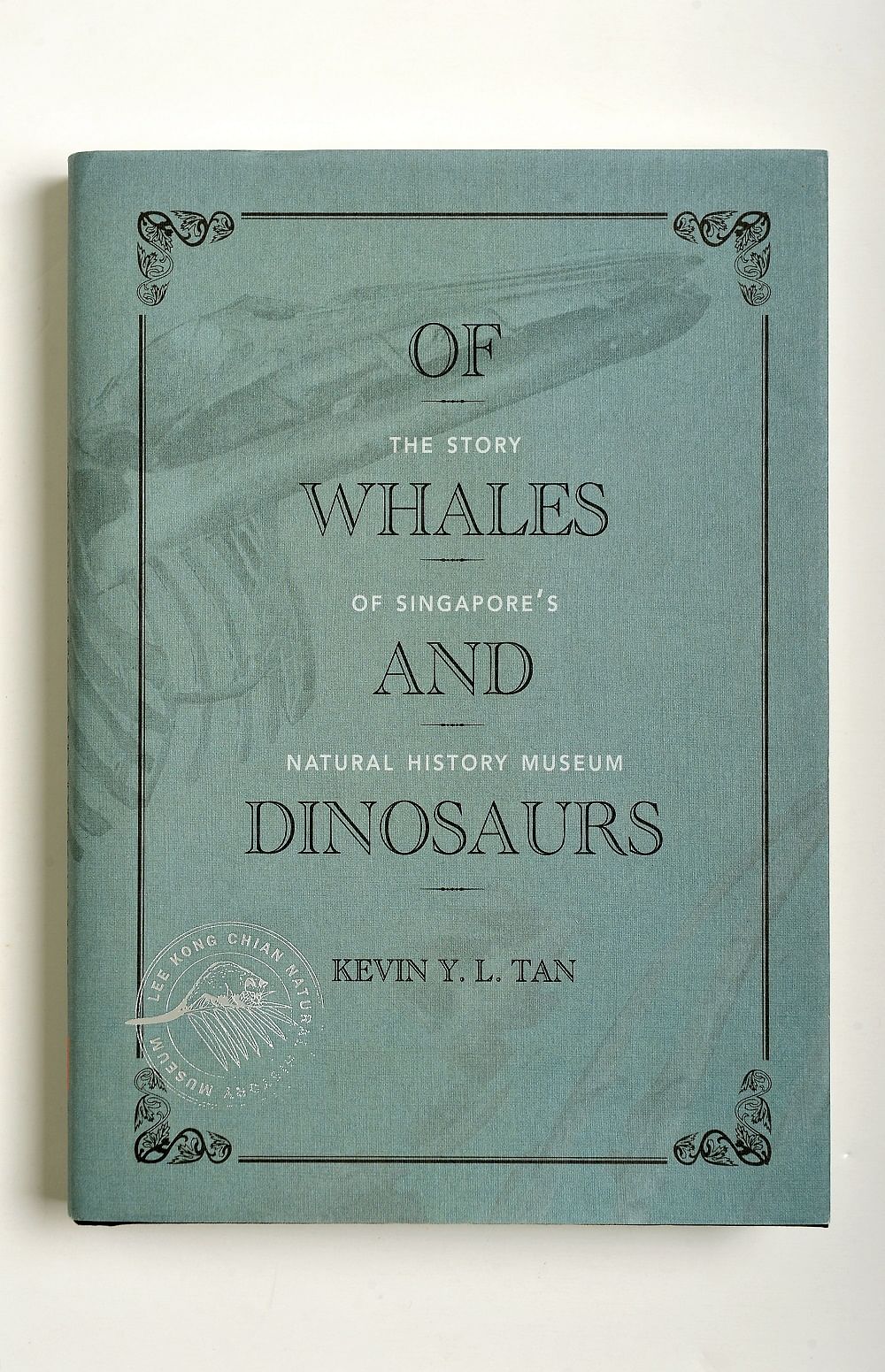

In view of the substantial support of the Lee Foundation, it was decided that the new museum would be named after its founder. Furthermore, Dr Lee Kong Chian was closely associated with the first local Chancellor of the University of Singapore (the predecessor of NUS). The new institution would now be named the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum.

Ingredient number 2 - an endowment plan - was now in place.

In May 2014, Ng - hitherto Director of RMBR - was appointed Head of the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum. In view of the growing importance of the new museum for research and education, and its substantial endowment, NUS decided that it would be an independent academic unit in the Faculty of Science, a de facto new department. It may be recalled that Lee Kong Chian had been the philanthropist whose donation in 1953 allowed the Raffles Library to break away from the museum and be transformed into a public library. As fate would have it, through its donation to the museum, the Lee Foundation has now helped rescue the "other half" of the old Raffles Museum and Library from oblivion.

One evening, just as the fund-raising for the museum was coming to a close, the university president urgently sought out Ng and Tan.

As it was already past 6pm and the call sounded urgent, they feared that something might have gone awry. Instead, they were met by an apologetic university president who told them that the promised site was no longer available (it was given to NUS-Yale) but that he could now offer them the site of the soon-to-be-vacated Estate Office.

This was music to the ears of Ng and Tan as they had concluded that this was in fact an even better site, given its greater accessibility and proximity to the University Cultural Centre, NUS Museum and the Yong Siew Toh Conservatory of Music. Ironically, the Kent Ridge Crescent location was the exact site the late Deputy Vice-Chancellor, Reginald Quahe, had offered to house the collection back in 1977.

Work on the building began on Jan 11, 2013, and was completed in the first quarter of 2015. The 8,500 sq m, seven-storey "green" building was designed by renowned home-grown architect Mok Wei Wei. Winner of the President's Design Award in 2007, he had worked on high-profile public projects such as the refurbishing of the National Museum as well as the Victoria Concert Hall and Theatre.

The book is available at bookstores at a retail price of $49.22 (including GST).