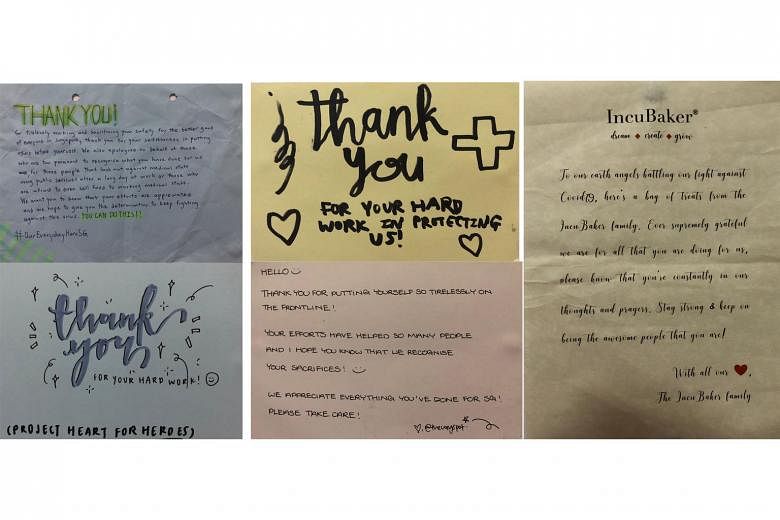

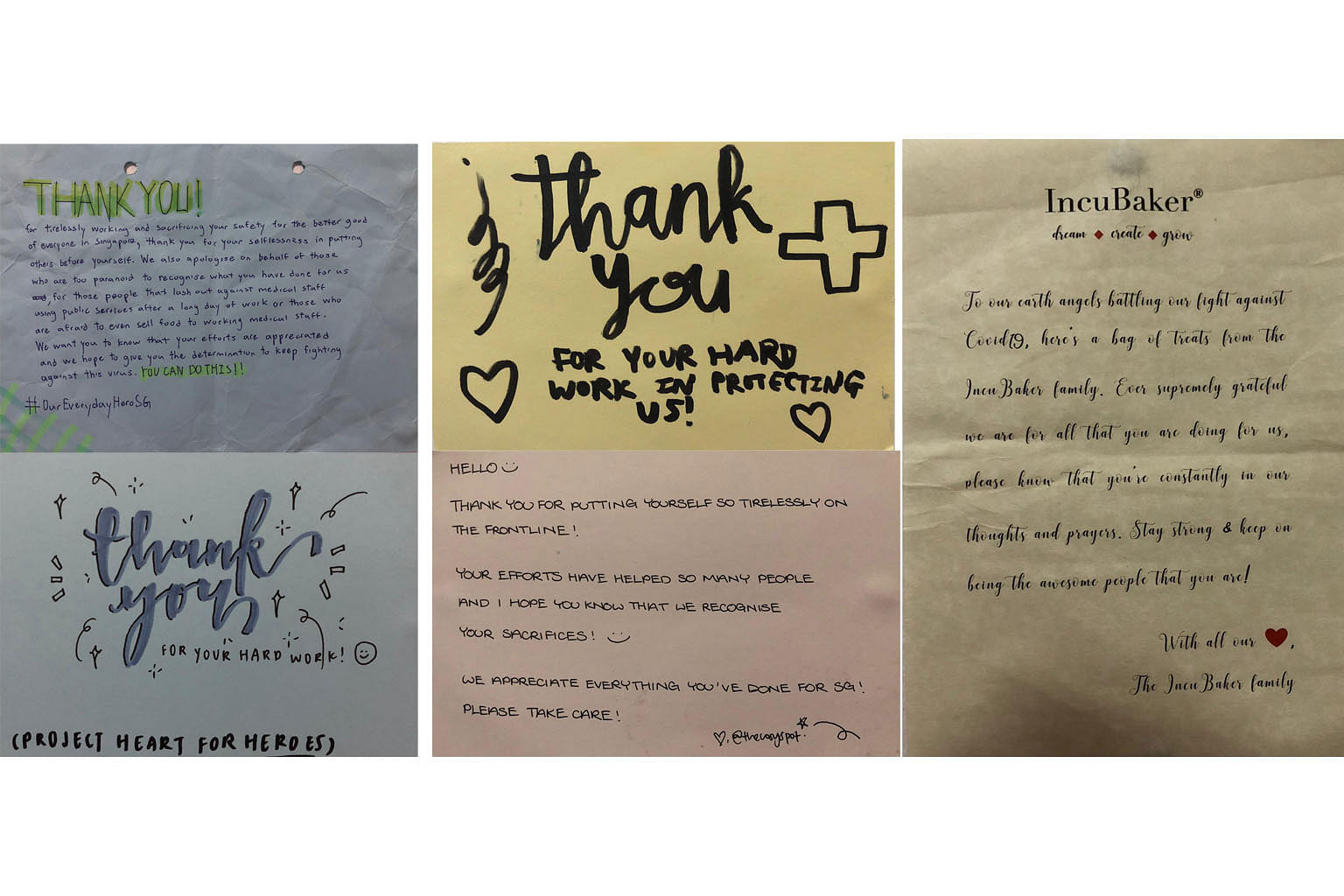

The cards provide motivation, they offer comfort, they are perhaps reminders of her purpose. The cards arrive at the hospital from strangers, scribbles on blue paper, hearts drawn in black, and she takes these home and sticks them to her wall.

"Thank you," the cards say.

Thank you for "sacrificing your safety for the better good of Singapore". Thank you "for your hard work in protecting us".

Every day Ms Ling Ging Poh looks at those cards and then she walks from her home to the National Centre for Infectious Diseases (NCID), which is treating only Covid-19 patients, enters the intensive care unit, puts on her personal protective equipment with its N95 mask, goggles, gown, gloves, shower cap to keep her hair in place, and then enters a patient's room.

We carefully distance ourselves from Covid-19 but Ms Ling is a nurse and so she must advance towards it. Heroes, we sometimes like to say of her tribe, but she won't wear that casual label. "I think I'm not a hero," she says quietly. "I just try my best to help."

This is her daily job, her chosen life, and her armour is conviction, training and cutting-edge equipment. Each part matters in this pandemic. Asked how she feels about nurses in other lands, who must confront this virus with inadequate equipment, and she pauses:

"I feel heartbroken."

Only this gowned sisterhood, this masked brotherhood, understands the uncertain world within Covid-19 wards, only they know what it's like to wear these suits - "claustrophobic", she says - and offer care. Crisis binds people and when asked if this has happened with the nurses, she says: "Yes, yes."

"Because we are in the same boat, we have to support each other and we share information, help each other, and our bond will get closer and closer. And of course when we face any difficulties, we will also share with each other and find a solution."

From the outside we see only passing images of wards across the world and clips of staff bustling down busy corridors. Long days distilled to a handful of newsworthy seconds. But television can't translate the tension of patients in distress rolling into hospitals, it can't completely convey the endless shifts that nurses and doctors spend on their feet - Ms Ling's longest was 13 hours - as they try to unravel the reach of this new enemy.

It's why the cards on her wall matter because, first, they represent a city reaching out. Nurses worldwide have elicited the best from us and the worst, applauded from balconies in some lands, yet spat on and sidled away from in others. No such rudeness has been visited on Ms Ling, but one of her nursing friends had a less than pleasant experience.

"She joined a fitness class," says Ms Ling, "and they have to sign a declaration form. One of the questions is, 'Have you ever had close contact with a positive patient?' So of course she ticked the 'yes' box. Next day her membership was terminated."

The cards speak of kindness but they also fortify her, and on her wall, on top of the stuck-on cards, she has pasted these words: "Encouragement Corner. Fighting!!!"

This virus is a daily struggle and if you ask her what goes through her mind as her day commences, she is direct: "I guess it is fear and stress of work. But I tell myself to stay positive. I always pray to God for protection, let me go to work and come (home) safely. I stay calm at work no matter what situation arises."

Ms Ling is 24, considers her words carefully, has a smile that unfolds shyly and is a Singapore permanent resident. She lives in a room in a shared apartment, with no one to comfort her on hard days and yet no child to fear infecting. She hails from Sarawak in Malaysia and while there her parents wait to see her, here she tends to us.

Parents might offer unconditional love to their children, but nurses provide unconditional care to strangers. Like soldiers who cannot choose wars, nurses cannot choose outbreaks or patients, and only during a crisis does the larger population see them clearly.

Experience is its own shield in a pandemic. Some nurses here have jousted with Sars, but for some Covid-19 is a first major crisis. Ms Ling has a diploma in nursing and also a degree, has worked in Tan Tock Seng Hospital for three years and at the NCID for over a year, but the sheer foreignness of Covid-19 has brought its own challenge.

The everyday healing of humans can be a taxing business but this, she says, is very different.

"Before the pandemic we still experienced stress at work but not so much stress as compared to now because we don't know what this disease is about."

Nurses are accustomed to suffering but this virus' sly ability to spread has resulted in something profoundly sad: It allows for no goodbyes. And so, for Ms Ling, the hardest thing has been "when a patient passes away and the family can't be at the bedside, can't hold their hands and say their last goodbyes".

Five days a week Ms Ling works, on one of the three rotating shifts, wrapping herself in protective layers every time she enters a patient's room, sometimes even donning a suit with an air-purifying respirator and a hood when they are doing a procedure that generates aerosols or droplets.

Equipment brings confidence but nothing can completely shelter a human from apprehension. No nurses in Singapore have been killed by Covid-19, though to flick through a Twitter handle like NursingNotesUK, which relays health news in the United Kingdom, is to be met by a grim list of the nursing dead.

And so Ms Ling's fears are understandable, "of being socially isolated, and of course of being infected", and yet she is reassured by the very system she works in. "I believe in our healthcare system because it is well established. So I have the confidence if one day I will be infected, I will be well taken care of by the healthcare team."

There have been bad days, says Ms Ling, of many admissions and good days of patients transferred out to general wards. This pandemic will go on till one day it will be behind her, and us, and to borrow a line from novelist Haruki Murakami, "once the storm is over you won't remember how you made it through". Till then, long days. Till then, she will walk home after work, call her parents to check on them, flick on Netflix, listen to her favourite Chinese music and cook something. Till then, sleep and perhaps next morning new cards from grateful strangers.

Ms Ling's shifts, in a way, will never end because disease never does. This is the nurse's life, of mostly anonymous and enduring service, and poet Walt Whitman, who spent time as a hospital volunteer during the Civil War, captured this duty beautifully in a single line in his poem, The Wound-Dresser:

"I am faithful, I do not give out."