Yesterday afternoon, Mrs Jek Yeun Thong, 83, put on a black dress, clasped a necklace around her neck and slipped on a pair of embroidered sandals.

As she dressed, she took care not to tell her husband where she was going: Mr Othman Wok's memorial service.

Mr Jek, Singapore's first minister for labour after independence, is now 86 and has been bedridden the past two years after suffering two strokes.

His wife told The Straits Times: "I don't want him upset. The past few times, when I told him that someone had died, he cried."

With the passage of time there is, understandably, a sense of loss when another Old Guard leader leaves the scene.

With Mr Othman's passing on Monday, two members of that august band of first-generation leaders from the People's Action Party (PAP) remain: Mr Jek and Mr Ong Pang Boon, 88, the country's first home affairs minister.

Throw the net wider to include the 64 members of Singapore's first Parliament, and seven are known to be living, having made rare public appearances.

It is a generation of which much has been written, but whose story bears telling again and again. A constant thread is the sacrifices made. Not least among them was Mr Othman.

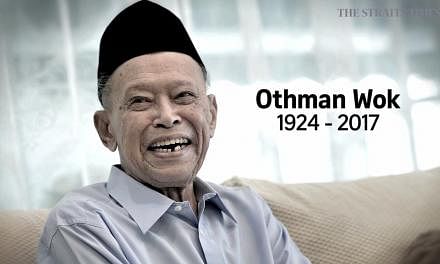

He died on Monday, aged 92.

As the most senior of the PAP's Malay members in the 1960s, he was the one person most prominently put in the position of being caught between the visceral pull of race and the need to form a multicultural nation, as Singapore and Kuala Lumpur battled over the kind of Malaysia that should emerge.

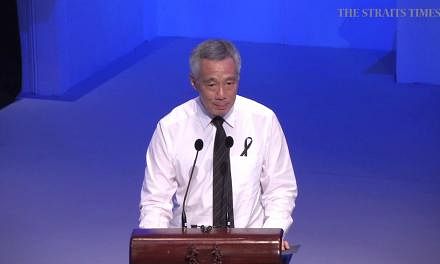

In the process, Mr Othman and his colleagues came under immense pressure. They were branded kafirs or infidels, recounted Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong yesterday. They received death threats. Some of Mr Othman's posters were smeared with faeces.

But he never wavered, and "not a single Malay PAP Legislative Assemblyman jumped ship, though they knew they would have been richly rewarded had they done so".

That sense of putting nation - at a time when it was still an inchoate entity - over self, family and community was hardly limited to Mr Othman.

Yesterday, Mr Ong, who walked unaided to his front-row seat next to Mr Othman's family, listened intently as Dr Janil Puthucheary paid tribute to his generation:

"All communities gave up something, all our people sacrificed something, majority and minorities alike together - language, religious practice, dress codes, social customs, aspects of education.

"We were all prepared to give up something for the greater good. We developed a consciousness that in matters of racial harmony, giving was better than taking, sacrifice and compromise were better than winning."

It would have resonated with Mr Ong, who incidentally was introduced to PAP's leaders in 1955 by Dr Puthucheary's uncle James, a fellow member of the University of Malaya Socialist Club.

As minister for education from 1963 to 1970, Mr Ong spearheaded the bilingual policy in 1966 making it compulsory for students to learn two languages, including the teaching of English in Chinese vernacular schools.

It paved the way for English to become Singapore's common working language, and also eventually led to a shift in the predominant language spoken at home. This became English.

A Chinese-educated KL boy himself, Mr Ong then had to convince the Chinese-speaking community to subsume their communal interests under national interests - even as it came at the cost of a generation that felt itself culturally displaced.

The Old Guard's ethos of multiracialism is more important than ever today, with the rise of extreme ideologies, as Minister-in-charge of Muslim Affairs Yaacob Ibrahim put it.

And PM Lee yesterday recounted what Mr Othman had said at one of his last interviews: "You cannot just, like Kuan Yew says, go on auto-pilot … Our future generations must continue to build on things. Do not lose focus on sensitive issues such as race, language and religion."

Now, Singapore's survival is not the principal concern for many of those from the first generation, given their own dignified struggles with the afflictions of time.

Mr Ho Kah Leong, 80, a former parliamentary secretary, chuckled at his own efforts, saying yesterday at the Victoria Concert Hall: "I swim, exercise and paint. I try to keep active."

Mr Othman too remained light of heart and pursued his other interests in his years after politics.

He gained a following of fans when he compiled ghost stories that he had written in Jawi in the early 1950s, into a book titled Malayan Horrors. Even as he later battled cancer, he organised makan sessions with friends and burnished his reputation as a joker who loved to tease his friends.

When looking back at his contributions in his biography, he wrote: "Where my contribution to Singapore is concerned, I leave it for others to judge me. I think I've done the best that I could do."

And yesterday, as the national anthem played in Mr Othman's honour, and his peers rose somewhat unsteadily to their feet, that is a sentiment that perhaps most of them feel just as keenly.