SINGAPORE – Deep in a peat swamp forest in southern Sumatra, an Indonesian researcher and his team swam across a muddy river and climbed a giant tree once a month for more than a year to get a closer look at what they suspected to be a new tree species.

After collecting and studying enough flowers, fruits and leaves – while keeping away from tigers prowling the forest – the researcher, Mr Agusti Randi, and his colleagues in Singapore confirmed that it is a new record for peat flora.

The new 40m-tall peat tree – named Lophopetalum tanahgambut, which translates into “the peatland crowned petal” from Latin and Bahasa Indonesia – adds to the understudied but potentially growing list of around 350 species of trees in the scarce peat swamp forests of South-east Asia.

Peat swamp is formed when tropical forest trees grow in water-logged soil. When leaves and other tree debris fall off, they decompose slowly because of the wet ground. Therefore, peat lands are known to be strong carbon sponges, storing huge amounts of carbon in the form of accumulated dead plant matter.

But peat swamps have heavily declined in Indonesia due to decades of logging, draining and burning to turn the fragile habitat into plantations to produce raw materials for palm oil, and pulp and paper.

Mr Randi is a research assistant at the National University of Singapore (NUS) Environmental Research Institute’s Integrated Tropical Peatlands Research Programme.

The programme’s co-lead, Dr Lahiru Wijedasa, said: “If you want to restore the peat swamp, you first need to know what the plants are.”

In 2017, the scientists were near Sumatra’s Jambi province, mapping the forest area’s flora. Among the vegetation they surveyed, up to seven types were unfamiliar to the scientists. One of them was the Lophopetalum tanahgambut.

From the vein patterns on the giant tree’s leaves, Mr Randi suspected it belonged to the Lophopetalum genus, but its leaves are arranged in an unfamiliar manner. The scientists had a hunch that the tree could be a new species.

But Lophopetalum trees are identified through their flowers, and the scientists had missed the flowering season. So they resumed regular fieldwork in late 2020.

To track the tree’s growth and collect more samples such as fruits and buds, Mr Randi and his team returned to the tree every month, repeatedly going through the rigour of swimming across the river and scaling the giant.

As they became more familiar with the site over the months, they also found nine more Lophopetalum tanahgambut trees.

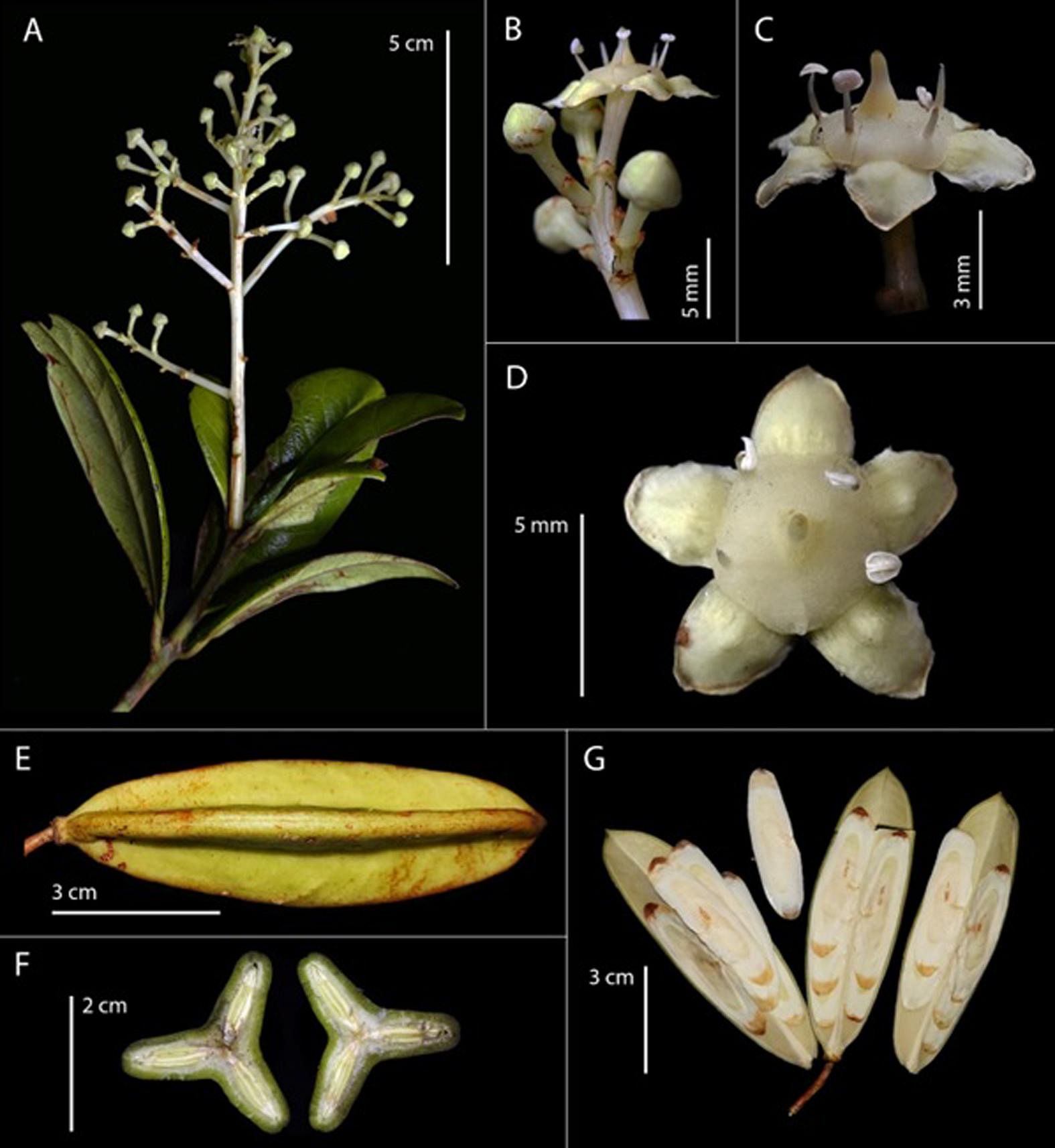

In April 2022, they finally captured the tree in full bloom and were able to confirm that it is a new species of Lophopetalum. They worked with experts from Britain’s Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, to describe the species completely. Their findings were published in scientific journal Phytotaxa on Nov 17.

“I have described and published quite a lot on new species, but this one is very special for me. It took a long time to wait and collect all the tree’s (features),” said Mr Randi.

The Lophopetalum tanahgambut is the team’s second peat tree discovery in southern Sumatra under the NUS research programme. Their first one, whose discovery was published in January, is the first new find of a peat swamp tree in almost 60 years.

Work continues on the other five unidentified trees, which could be new species too.

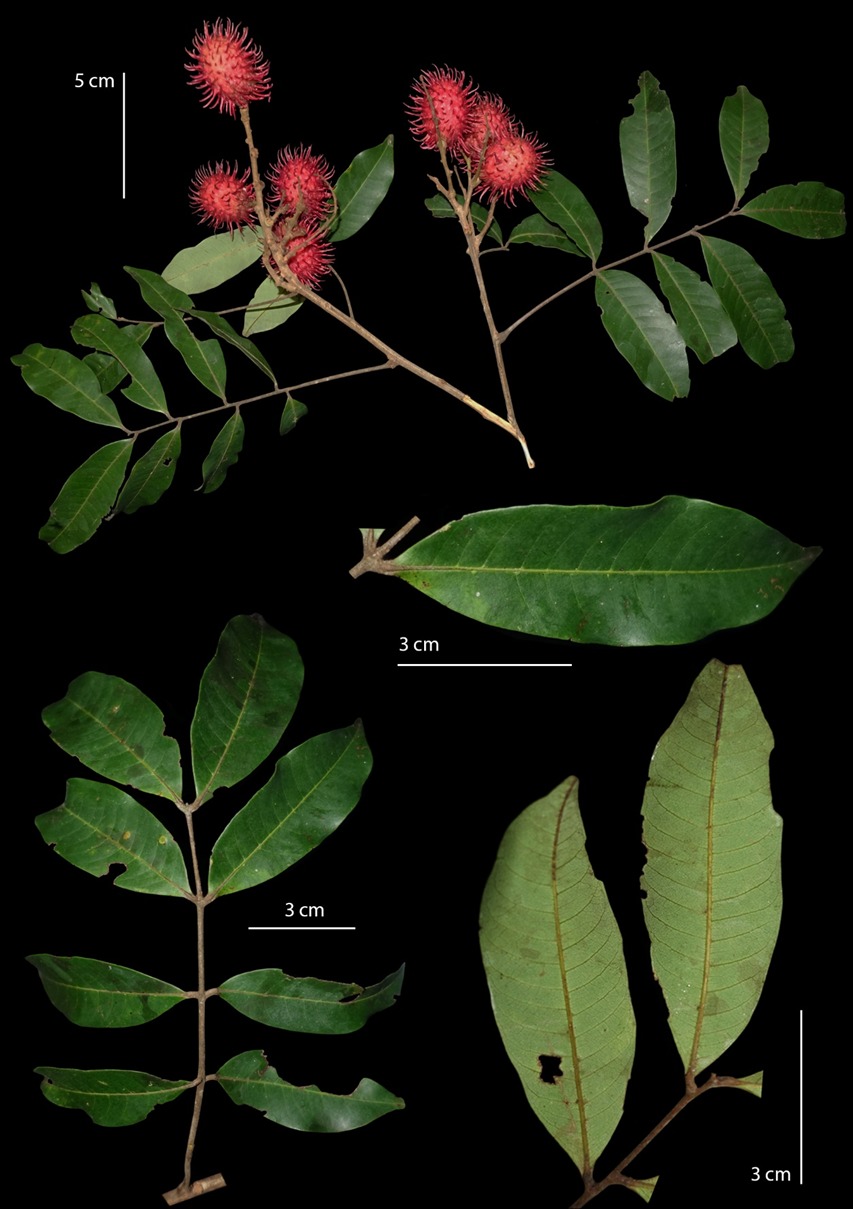

By 2023, Dr Lahiru and Mr Randi, alongside more than 50 botanists in the region, aim to publish a book detailing the peat swamp flora of South-east Asia. On top of describing each species, the guide will also give ecological information about each plant. The lesser-known peatland rambutans and durians will also be featured.

But describing peat tree species is the easy part, said Dr Lahiru.

“The difficult stuff comes after this. Once you know the plants, the difficult part is knowing how to use this information to restore the ecosystem.”

In 2016, Indonesia launched the Badan Restorasi Gambut, an agency tasked with restoring 2.49 million ha of the archipelago’s most vulnerable peatlands over five years. Its mandate has since been extended to 2024 and expanded to include mangrove restoration.

Professor Gusti Anshari from West Kalimantan’s Tanjungpura University, who was not involved in the research, said: “At present, most seedlings for restoration are collected from the remaining peat forests, and the quality of these wildings are generally poor. We need to enhance natural regeneration and control disturbances (by human activities) that cause degradation.

“The work of Lahiru is important if he could identify favourable sites for speeding up restoration, and help nature restore.”

Dr Lahiru said: “We stand by the principle that there needs to be the right plant for the right site. In the peat swamps, you need plants that can survive the acidic soil, the very low nutrients, the flooding. Peatlands are probably the hardest things to restore.”

In the near future, Mr Randi and Dr Lahiru are looking to grow peat tree saplings in nurseries to identify each species’ ideal growth conditions. For example, they hope to identify plants that can grow in degraded or burnt peatlands.