Most immune responses genetically determined

Nearly three-quarters of immune traits are influenced by genes.

A study by King's College London, published in Nature Communications, has added to a growing body of evidence that the genetic influence on the human immune system is significantly higher than previously thought, said the university in a statement.

Researchers analysed 23,000 immune traits in 497 adult female twins. They found that adaptive immune traits - the more complex responses that develop after exposure to a specific pathogen, such as chickenpox - are mostly influenced by genetics.

They also highlighted the importance of environmental influences such as diet on shaping innate immunity - the simple core immune response found in all animals - in adult life.

The findings could help to improve understanding of the immune system and the interaction of environmental factors, and also boost further research into treatments for various diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis.

Said Dr Massimo Mangino, the lead researcher from King's College London: "Our genetic analysis resulted in some unusual findings where adaptive immune responses, which are far more complex in nature, appear to be more influenced by variations in the genome than we had previously thought.

"In contrast, variation in innate responses more often arose from environmental differences.

"This discovery could have a significant impact in treating a number of autoimmune diseases."

Professor Tim Spector, director of the TwinsUK Registry at King's College London, said: "Our results surprisingly showed how most immune responses are genetic, very personalised and finely tuned. What this means is that we are likely to respond in a very individualised way to an infection such as a virus - or an allergen such as a house-dust mite causing asthma.

"This may have big implications for future personalised therapy."

Singapore, Israel working on cyber security together

Singapore's National Research Foundation (NRF) and Israel's Tel Aviv University (TAU) have awarded four cyber security research projects under the NRF-TAU collaboration programme, in areas including improving cyber security and deterring threats.

The programme was launched last year and aims to support collaborative research projects on enhancing cyber security for the Smart Nation initiative and the Internet of Things, behavioural and social science studies of cyber security and cyber security policy and governance.

Mr George Loh, NRF's director of programmes and co-chair of the National Cybersecurity R&D Programme Committee, said: "Cyber security is a global threat which extends beyond national boundaries."

He added: "These projects will also strengthen the design of our Smart Nation interfaces - for example, to automatically provide user-centric security policies on mobile devices based on a user's profile such as mobile usage or age."

Secret of skin cell development discovered

As early humans shed the hairy coats of their closest evolutionary ancestors, they also gained a distinct feature that would prove critical to their success: a type of sweat gland that allows the body to cool down quickly.

Those tiny glands allow humans to live in a wide variety of climates and run long distances.

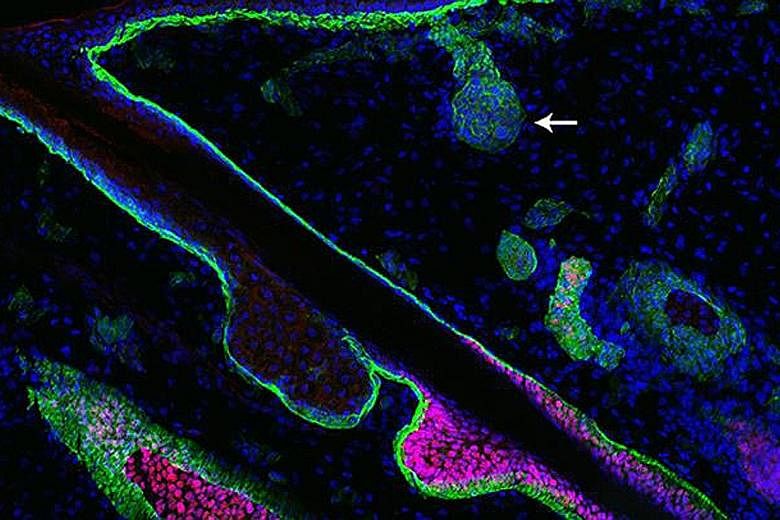

Scientists at Rockefeller University have identified the molecular underpinnings that guide the formation of both hair follicles and sweat glands. They found that two opposing signalling pathways - which can suppress one another - determine what developing skin cells become.

By looking at different developmental stages of human embryonic skin, the researchers discovered that hair follicles are born first, followed by a burst in signalling protein that allows sweat glands to emerge.

The findings have the potential to improve methods for culturing human skin tissue used in grafting procedures, said the university in a statement. Currently, patients receive new skin lacking the ability to sweat.

People with damaged sweat glands - such as burn victims and those with some genetic disorders - suffer from a life-threatening condition where they must remain in temperature-controlled environments and cannot exercise, because it could result in heatstroke and brain damage.