The world is intensifying its search for more renewable energy sources in a bid to curb greenhouse gas emissions, and a new discovery by scientists in Singapore could help it better soak up the sun.

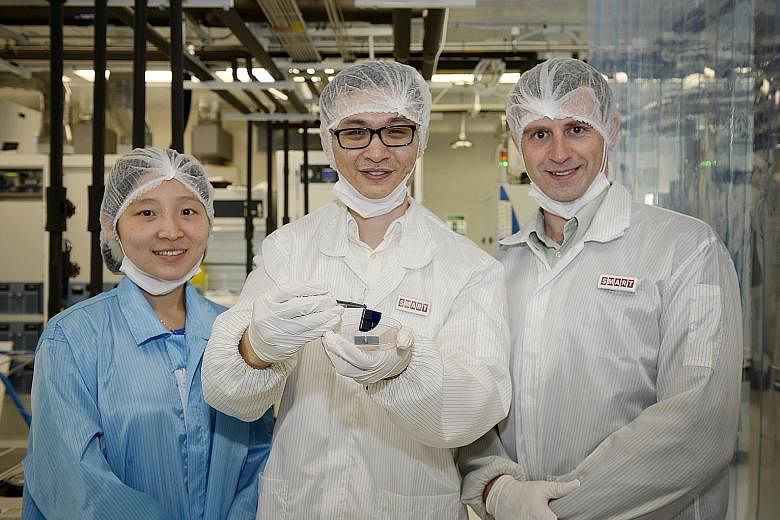

They have created a solar cell with 21.3 per cent efficiency - the highest measured for a cell made completely in Singapore.

"Other solar cells made here usually have an efficiency of between 17 and 18 per cent," said Professor Tonio Buonassisi from the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology (Smart), one of two research leads on the project.

The efficiency of a solar cell is the proportion of energy from the sun it turns into electricity.

While there are solar cells made elsewhere with efficiencies of up to 24 per cent, these are usually more expensive. They cost about 50 per cent more than the silicon cells with efficiencies of about 18 per cent, said Professor Armin Aberle, the other research lead. He is the chief executive of the Solar Energy Research Institute of Singapore.

Light is electromagnetic radiation, some of which can be seen and some of which is invisible to the human eye. Infrared and ultraviolet radiation, for example, cannot be seen. They lie at either end of the visible spectrum of light.

Prof Buonassisi said today's solar cells tend to be made of silicon, and they convert near-infrared light quite efficiently into electricity. But they are less efficient for visible and ultraviolet light.

Scientists in Singapore have discovered that a new material, gallium arsenide, can be incorporated into a solar cell to help it convert the other colours more efficiently.

By layering the gallium arsenide on top of the silicon cell, more of the sun's energy can be captured and converted into electrical energy, said Prof Buonassisi.

The visible spectrum and ultraviolet light can be tapped in the top layer and the invisible spectrum passes through to be caught in the bottom layer.

The researchers also found that their solar cell had achieved its 21.3 per cent efficiency under more realistic, direct sunlight conditions, as opposed to concentrated sunlight conditions.

Direct sunlight is what a flat panel on a rooftop receives. Concentrated sunlight conditions are created with mirrors or lenses to focus the sunlight, and can be costly.

The Singapore team's twin-layer cells using gallium arsenide are still at a research phase, and Prof Aberle said there are other teams focusing on other materials, such as perovskites. "It will require a huge R&D effort, but there are good prospects that by 2025, the first prototypes will emerge in the market, with efficiencies of over 25 per cent.

"By 2030, we can expect panel efficiencies of 30 per cent," he said.

But the researchers added that the challenge is to develop a top cell that is both highly efficient for visible wavelengths and as cost-efficient as bottom silicon cells.

Prof Buonassisi said the team will continue to try and raise the efficiency of their solar cell by experimenting with other materials for the top layer.

He said: "Now that higher-efficiency technology has been developed, the industry, academia and research institutes can work together to come up with ways to manufacture them more cost-efficiently."