For more than a hundred years, only people with the Tan surname were allowed to worship at the temple nestled amid shophouses in Magazine Road near Clarke Quay.

Called Po Chiak Keng, which means protector of the innocent, it was a place to resolve disputes and where brotherhood was promoted among new migrants whose family name was Tan, or Chen in Hokkien.

The temple also served as a clan association called Tan Si Chong Su (Ancestral Hall of the Tan Clan).

The building was constructed from 1876 to 1878, funded by two men from prominent Tan families - Tan Kim Ching and Tan Beng Swee.

Tan Kim Ching was the eldest son of merchant and philanthropist Tan Tock Seng, who gave generously to the hospital later named after him. Tan Beng Swee's father, Tan Kim Seng, is best known for his donation to public waterworks here.

The younger Tans were both influential in the Chinese community.

The initial intention was to build a clan home but a temple was constructed to give the compound a better reputation. It was gazetted as a national monument in 1974 and sits on the same spot where it was first built. It was only in 1982 that the temple was opened to worshippers of other surnames.

Tan Si Chong Su chairman Andrew Tan, 31, said: "The clan home was set up in a time where there were a lot of triad societies, so to avoid confusion, a religious place of worship was incorporated as well."

Some believe the site was contributed by three people who owned a plot each - a Chinese whose surname was Tan, an Indian and a Malay. The site now belongs to the Singapore Land Authority.

Ancestral tablets of those surnamed Tan are kept in the hall near the back of the compound. Families with nine other surnames believed to share a common ancestry with the Tans are also allowed to place their tablets in the clan.

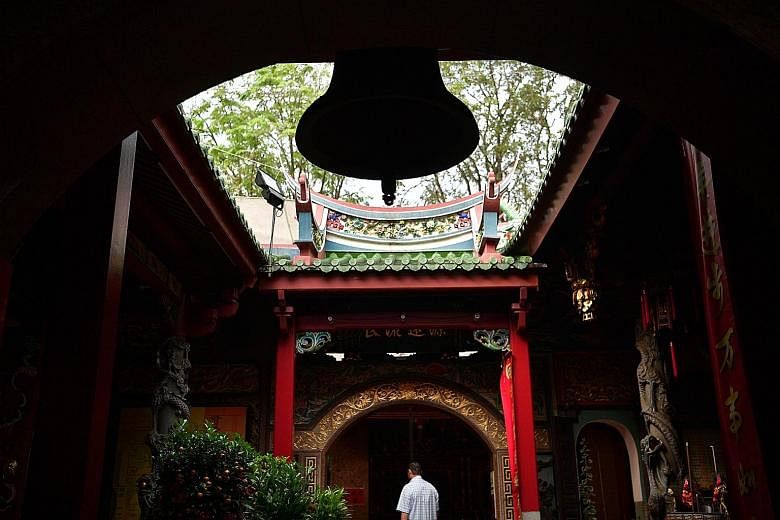

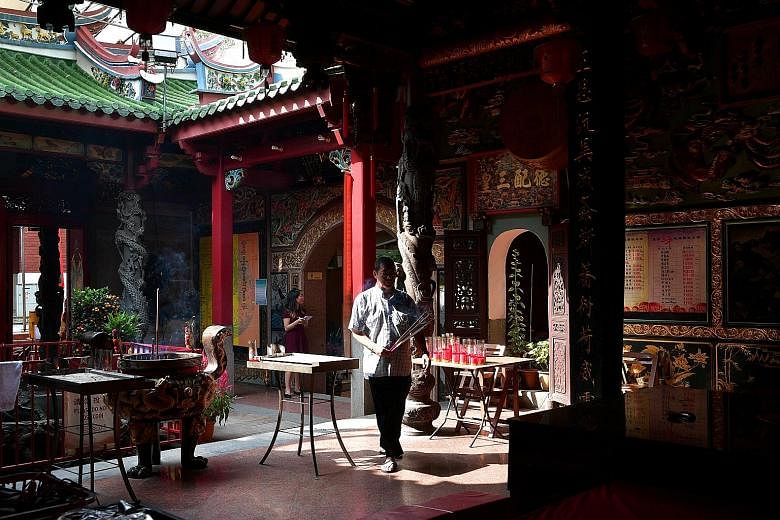

The temple's design is considered unique, especially in Singapore. The San Chuan Dian, or three-tier hall, at the entrance of the temple is more common in southern China. It is symmetrical, with a wider main gate and one smaller gate on either side.

The front of the temple is adorned by two windows, known as Zi Wu Chuang, which are present only in very traditional temples. Its design depicts an incense pot surrounded by dragons.

The dragons are meant to represent the Dragon King, a water deity.

By encircling the incense pot, they signify a blessing that the temple will continue to be prosperous and draw more worshippers.

Two pillars at the entrance hall of the temple feature dragons carved out of solid granite.

Dr Tan points to how the dragon has three claws on each foot.

"This is because the emperor at the time did not decree that this temple be built. If the emperor commissioned a temple, the dragons would have five claws," he said, lamenting that newer temples often overlook these details.

Beyond the entrance hall lies a prayer hall, where devotees offer incense and pray. Inside the hall, two bells and a drum dating to the 19th century hang from the ceiling.

Lanterns with wishes and requests are also suspended in front of the deities, including the chief deity of this temple, Sagely King Chen.

Originally known as Chen Yuanguang, he was a general and official in the Tang dynasty. After being credited for ruling towns in southern China wisely and helping the region prosper, he was deified and worshipped.

In Singapore, Tan is the most common surname - almost 240,000 or 10 per cent of the local Chinese population share this family name, according to a 2000 figure from the Department of Statistics.

However, not everyone is happy that this temple under the Tan clan is now open to everyone.

In 2007, four men from one of the local Tan clans took Po Chiak Keng to court for allowing non-Tans to pray at the temple, fearing that the deity would be endangered.

Justice Choo Han Teck dismissed their lawsuit and those of other surnames continue to pray at the temple.

One such devotee is Mr Hou Yu Jun, 40, who has been worshipping at the temple since 2007.

He said while he visits many temples, this is the one he comes back to regularly because he feels a connection to Sagely King Chen.

"Whenever I come here, I learn something new. Some (features) of the architecture tell stories that teach me new values," he added.

Mr Hou, a manager in real estate, usually visits alone and finds his mind at peace in the temple.

Another devotee, shipping manager Rosanne Tan, 31, said: "My grandfather and father were all very involved in the activities at the temple. Now I am close to the community here, many devotees are just like family to me."