I suppose I could sit here and fret over a day in the not-too-distant future when a robot powered by artificial intelligence(AI) will spit out newspaper columns like this one, rendering redundant columnists like me. After all, there have been reports that computers can already churn out news reports that read almost as well as those written by journalists, and in a fraction of the time taken.

The thought of being replaced by software is depressing and, I might add, self-defeating.

That is why I disagree with the way technological advances and the future of work are all too often framed in either-or terms: either robot or human worker, either AI or human brain.

Here are a few recent examples of headlines in local media that fall into this category : "AI may replace a third of graduate jobs: Study", published on April 6; "Evidence that robots are winning the race for American jobs", published on March 30; and "Robots may take over 10 million jobs in Britain in 15 years", published on March 25.

Such reports reflect how automation and AI are more often than not viewed - not just in Singapore but in other parts of the world too - as threats to jobs and human well-being. An extreme example of such thinking is exemplified by historian Yuval Noah Harari, author of the best-selling book Sapiens: A Brief History Of Humankind.

In an essay for ideas.ted.com bearing the headline The Rise Of The Useless Class, he writes: "The most important question in 21st-century economics may well be: What should we do with all the superfluous people, once we have highly intelligent non-conscious algorithms that can do almost everything better than humans?"

He adds that "the idea that humans will always have a unique ability beyond the reach of non-conscious algorithms is just wishful thinking" because "every animal - including Homo sapiens - is an assemblage of organic algorithms shaped by natural selection over millions of years of evolution".

I question if human beings can be reduced to "assemblages of organic algorithms" but even if that view has some basis, it remains unclear what time frame Mr Harari has in mind for his doomsday scenario.

For the foreseeable future, though, I propose a reframing of the challenge, along the lines put forth in a 2015 Harvard Business Review (HBR) article by Professor Thomas H. Davenport and Ms Julia Kirby entitled Beyond Automation.

They write: "What if we were to reframe the situation?

"What if, rather than asking the traditional question - what tasks currently performed by humans will soon be done more cheaply and rapidly by machines? - we ask a new one: what new feats might people achieve if they had better thinking machines to assist them?

"Instead of seeing work as a zero-sum game with machines taking an ever greater share, we might see growing possibilities for employment.

"We could reframe the threat of automation as an opportunity for augmentation."

New feats, growing possibilities for employment, opportunity for augmentation - such phrases are not common currency in talk on the future of work. Yet they should be.

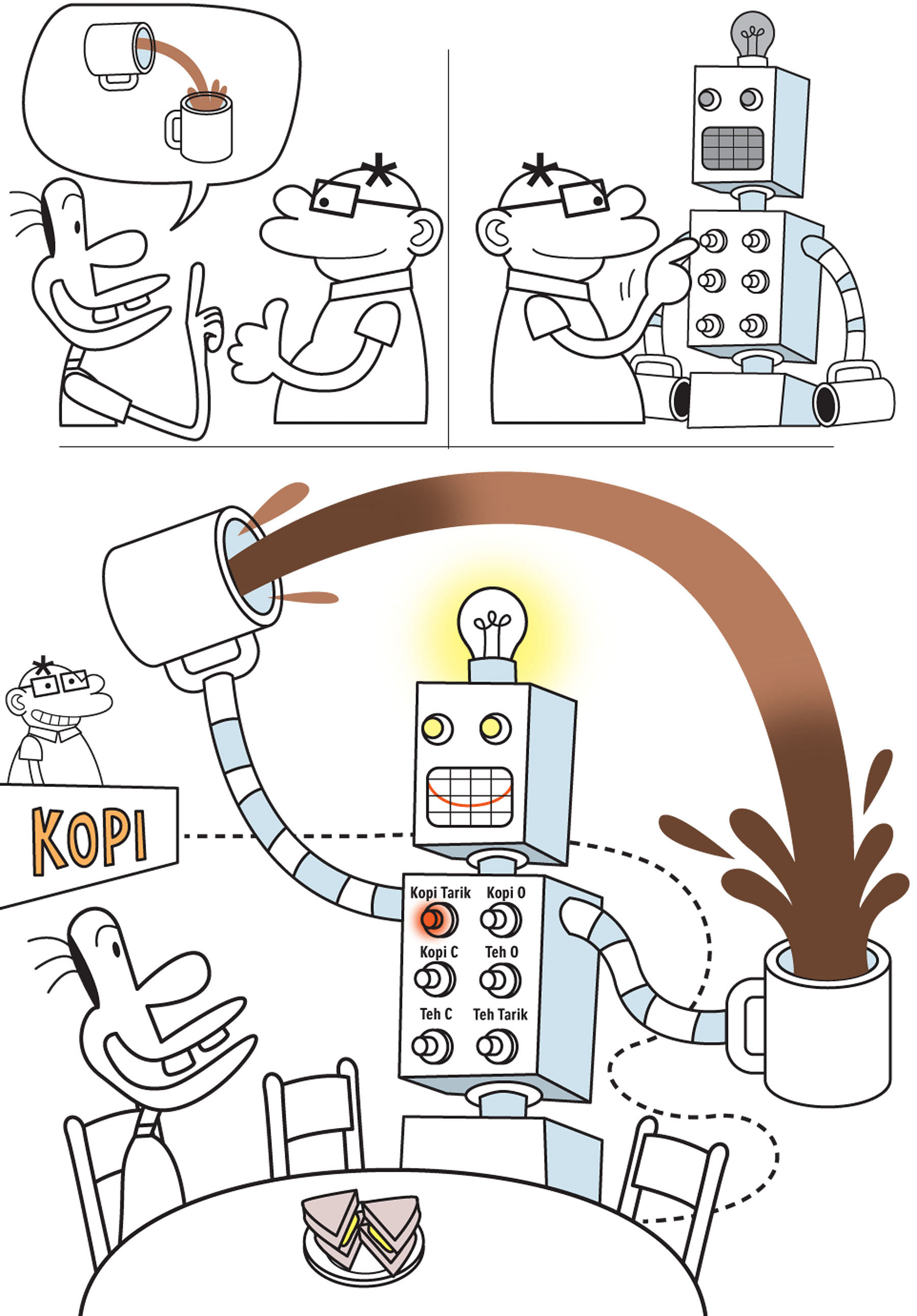

A change of focus from automation to augmentation changes the outlook for humans.

The first implies they will be replaced by robots while the second points to them collaborating with robots to achieve that which is impossible today.

Such a paradigm shift has the power to unlock human potential for it encourages people to stop agonising over cost and headcount cuts and imagine instead ways to bring about growth - business growth, economic growth, personal and professional growth.

I take heart that the man championing this paradigm shift from automation to augmentation - Prof Davenport - is considered an expert in information technology and management. A research fellow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Centre for Digital Business, he penned the article with Ms Kirby, an HBR editor-at-large.

They also quote MIT economist David Autor, who closely tracks the effects of automation on labour markets and points to the immense challenge of applying machines to tasks that call for flexibility, judgment or common sense.

He says: "Tasks that cannot be substituted by computerisation are generally complemented by it", a point that "is as fundamental as it is overlooked".

So what to make of those dire forecasts of millions of jobs - including graduate jobs - being lost to robots and AI? My sense is they are unhelpful. The impact of technology differs from place to place, depending on context and local circumstances. The rise of robots is much less of a concern for a small, labour-scarce country like Singapore than it is for a large, labour-rich one like China.

Worries about mass unemployment may in fact be overblown, the McKinsey Global Institute concludes in a report issued in January - A Future That Works: Automation, Employment And Productivity.

"While much of the current debate about automation has focused on the potential for mass unemployment, predicated on a surplus of human labour, the world's economy will actually need every erg of human labour working, in addition to the robots, to overcome demographic ageing trends in both developed and developing economies.

"In other words, a surplus of human labour is much less likely to occur than a deficit of human labour, unless automation is deployed widely," the McKinsey team writes.

Yes, the nature of work will change. As processes are transformed by automation of certain tasks, "people will perform activities that are complementary to the work that machines do (and vice versa)". The key word here is complementary, that is, humans and robots working together.

There will also be changes in how companies are organised, the bases of industry competition and business models. So yes, there will be disruption and humans will have to adapt. But the McKinsey report presents a more nuanced picture of what will happen to jobs by breaking them down into activities.

"We consider work activities a more relevant and useful measure since occupations are made up of a range of activities with different potential for automation.

"For example, a retail salesperson will spend some time interacting with customers, stocking shelves, or ringing up sales. Each of these activities is distinct and requires different capabilities to perform successfully," the McKinsey team explains.

Its research shows that based on current technology, the three types of activities most susceptible to automation are: physical activity or operating machinery in a predictable environment, collecting data and processing data.

It estimates that "less than 5 per cent of occupations can be fully automated" and "about 60 per cent have at least 30 per cent of activities that can technically be automated".

"Workers", it concludes, "will need to work more closely with technology, freeing up more time to focus on intrinsically human capabilities that machines cannot yet match."

It would be sweet irony if the entry of robots into the workplace helps us become more fully human. I certainly look forward to that day, and to a machine helping me write better columns.