It is thought of as the diamond of the plant world - not just tough but also practically indestructible.

Indeed, the humble pollen grain is a potential gem that can be used as a natural drug capsule, say scientists from the Nanyang Technological University (NTU).

Pollen grains, the vehicles that transport the male sex cell of a plant from its male to female parts, or so-called flower sperms, could one day be the very same vehicles that deliver drugs into the human body. Instead of shielding the delicate male genetic material of plants from water loss and the ravages of the sun's rays, they would protect drug molecules from the gastric acid in the human stomach.

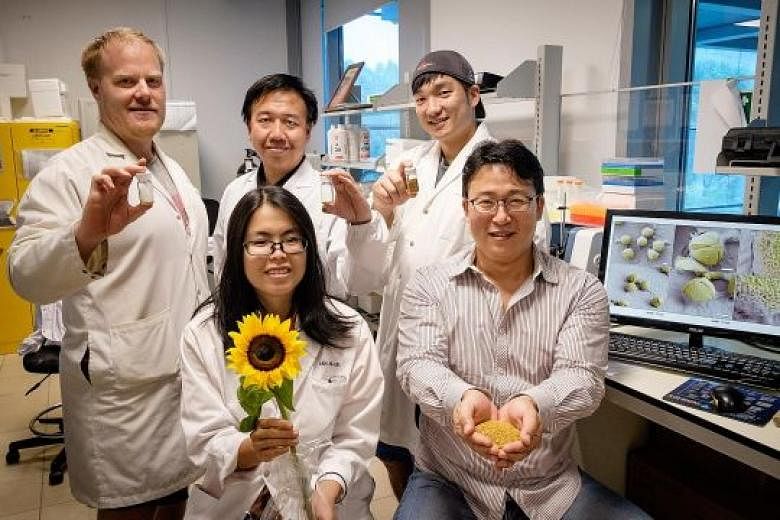

The NTU scientists have found a way to clear out the materials within pollen grains, leaving empty shells which are then used to encapsulate drug compounds, in a kind of tiny drug delivery system.

The findings have been published in several scientific journals, including Advanced Functional Materials last year.

Associate Professor Cho Nam Joon from NTU's School of Materials Science and Engineering said pollen grains are seen as the diamond of the plant world, having been discovered in geological strata dating back millions of years.

They can be used potentially to deliver therapeutic proteins, such as insulin, which are usually injected into patients. As these injections can be painful, patients often do not take the proteins as often as they ought to.

Such drugs are usually not taken orally as only negligible amounts make it past the harsh environment of the stomach to their intended delivery site.

Prof Cho said the development of synthetic microcapsules has improved the situation but such capsules are costly to create.

The raw materials needed for synthetic microcapsules cost some US$3,000 to US$10,000 (S$4,000 to S$13,000) per kg, but US$25 for pollen capsules.

"Pollen grains are a cheap, natural and sustainable alternative to synthetic microcapsules," he said.

They are also of uniform shape and sizes, and biocompatible - meaning not harmful or toxic to living tissue and so safe for humans.

Prof Cho's team has come up with a process to remove most of the genetic material from within the pollen grains, which uses phosphoric acid and takes less than 12 hours. Eventually, all the contents are removed.

In the process, they also removed the proteins found in pollen grains that are responsible for their allergenic properties, ruling out the chance of an allergic reaction.

Although pollen is extremely tough, the human body is able to break it down. In the team's experiments on sunflower pollen grains, which were cleared out, coated with a protective layer and used to encapsulate bovine serum albumin, a protein derived from cows, they found that the protein's release was inhibited for two hours in simulated gastric conditions.

However, all the protein was released within eight hours in simulated intestinal conditions.

"The data indicates the suitability of our tablet formulation to protect encapsulated proteins in gastric conditions and to target a significant portion of the intestinal area," the researchers said.

Professor Bang Sa Ik, vice-president of international affairs at Samsung Medical Centre, which is collaborating with the NTU team, said it is difficult to make high-quality microcapsules from synthetic materials as each particle needs to have identical properties, and it is hard to manufacture them on a large scale. There is also the challenge of finding biocompatible materials.

"One of the most exciting things about pollen is that it is already part of our daily lives. It is regularly eaten and many species are already approved by regulatory agencies as food products," he said.

The NTU team, which started their research into pollen five years ago and have received $2.5 million in funding, have also found other uses for them.

This includes using them to replace harmful plastic microbeads common in facial wash, toothpaste, cosmetics and other consumer products, whose disposal results in the sea being flooded with thousands of tonnes of waste each year.

What is pollen?

Pollen, also called flower sperm, comes in a variety of shapes and sizes.

Pollen grains can be round, oval, disc-or bean-shaped, smooth or spiky, and are naturally white, cream, yellow or orange.

Their sizes range from about 10 micrometres - one-tenth the width of a strand of human hair - to 200 micrometres.

Essentially, pollen is a fine powder made up of microspores produced by male plant parts. Pollen is vital for reproduction.

Each pollen grain contains male sex cells, comprising male genetic material.

During pollination, pollen grains are dispersed by animals or wind.

Some will find their way to female plant parts, where fertilisation takes place.

After fertilisation, a seed protected by a fruit is formed.

Pollen grains are known to be practically indestructible - even strong acid cannot destroy them.

They have been discovered in geological strata dating back millions of years.

Samantha Boh