Mr Thomas Tham Kwok Onn is dying to bring his father back to life.

Well, figuratively.

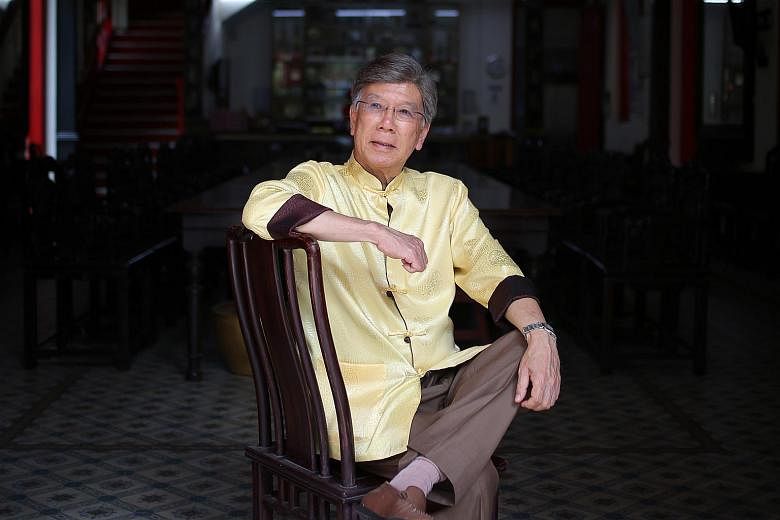

The 74-year-old businessman wants to revive Meng Kee Eating House, which his late father Tham Kwong Meng started in Chinatown in the 1940s.

For a long time, Meng Kee, along with other restaurants such as Kum Leng and Chew Kee, was an institution for Cantonese cuisine. It closed down in 1997, about two years before the elder Mr Tham died.

"People tell me: 'Your dad is dead but people still remember the restaurant and its signature dishes like roast chicken and sweet and sour pork. You should preserve the legacy,'" says Mr Tham, who still keeps in touch with his father's old staff.

The restaurant was well known not only for its roast chicken glazed with maltose and sweet and sour pork, but also for its list of patrons, which included Mr Pierre Trudeau.

The late Canadian prime minister first visited the restaurant in 1971 when he attended a Commonwealth meeting in Singapore, and turned up to have meals during subsequent private visits to the island.

Meng Kee is not Mr Tham's only dream. He also wants to rebuild a hair-transplant business, which he says was killed by red tape before it could take off in the late 1990s, as well as the fortune he once had.

Mr Tham, you see, was a serial entrepreneur and multimillionaire with a finger in every pie.

He founded and ran Eximwood, a timber company; Exim Fish, a deep-sea fishing outfit; Exim Arts, a string of home accessory outlets; Unicorn Realty, a property firm; Instant Glamour, a glamour photography shop; and Hair Harvest, a hair-restoration business.

Home for many years was a 5,000 sq ft house off Bukit Timah Road. He drove nice cars, ate well, holidayed often and led the good life.

But a series of business setbacks in the early 2000s took the wind out of his sails. He was also dealt a great emotional blow when the youngest of his four children - 15-year-old Tyrone - died suddenly from cardio-respiratory failure in 2002.

Major depression set in and he became suicidal. He sought psychiatric help at the Institute of Mental Health (IMH) and it took three years before he bounced back.

Eximwood and Exim Fish have been wound up, while Exim Arts was sold off a couple of years ago.

Although not a pauper, he has lost quite a lot of his fortune.

"Before I kick the bucket, I am determined to rebuild a couple of my businesses," he says over tea and scones at The Tanglin Club.

The eldest of five children, the gregarious and humorous septuagenarian grew up in Sago Lane, known for its funeral houses and where Meng Kee was initially located.

"In those days, the corpses were not embalmed. Sometimes you could see bodies on the street, covered with straw mats. It was a bit eerie," he says of his old neighbourhood.

He completed his primary and secondary education at Gan Eng Seng School, before attending Raffles Institution where he took his Higher School Certificate, the equivalent of today's A levels. "I had to help out at my father's restaurant every day after school, working both inside and outside the kitchen."

Active and playful, he took up lion dance and martial arts and was also an accomplished sea cadet.

His childhood ambition was to be a doctor, but he had to settle for pharmacy instead because his results were not good enough for medical school at the then University of Singapore.

True to the predictions of a fortune teller whom his mother consulted, pharmacy did not become Mr Tham's career.

Six months at a pharmaceutical company left him uninspired. So he quit and landed a highly coveted job as an executive with Intraco, a trading company formed by the Singapore Government in 1968.

"My job was to look for new markets, spot new opportunities and help local companies grow. I was put in charge of a new timber division and my portfolio included every industry related to timber, from paper to chairs to broomsticks," he says.

His mentor was the late Mr Sim Kee Boon, one of Singapore's pioneer civil servants, best known for overseeing the construction of Changi Airport and turning around the fortunes of Keppel Corporation.

"He taught me a lot. Some years after I left Intraco, I bumped into him checking the toilets at Changi Airport at night. We're talking about a top civil servant, a permanent secretary, the chairman of Keppel."

After three years at Intraco, where he developed extensive connections, Mr Tham formed a timber agency with a childhood friend.

The collaboration ended on a sour note barely six months later.

"I felt like Singapore being told to leave Malaysia," he says with a sigh.

But while it devastated him, the experience was also a game changer. He struck out on his own, plonking $10,000 of his savings to start Eximwood in a small office in Hongkong Street in 1973.

Among other things, he became a timber agent hooking up buyers from all over the world with merchants in the region.

"I was travelling to Europe, the Middle East and the United States meeting buyers, and going into the jungles of Sabah, Sarawak and Tawau looking for timber. It was quite risky. Sometimes we saw tigers and panthers."

Eximwood later went into manufacturing. It landed many big deals, one of which was supplying $2.4 million worth of knock-down furniture to Aramco, one of the world's biggest oil exporters.

Mr Tham soon developed an appetite for starting new ventures.

In 1984, he diversified into the marketing of frozen fish by setting up Exim Fish, which had its headquarters in Bangkok, with offices in Somalia and Saudi Arabia.

"We were fishing for lobsters from Somalia, shrimp from Iran and fish from the Gulf coast," he says, adding that Exim Fish had eight trawlers and a mother ship.

Next up was Exim Arts, which dealt in arts and crafts and knick- knacks. The business grew from just one outlet in Lau Pa Sat to 10 around the island.

He also set up a realty firm and invested in a few properties.

With all the money that he made, he went into the hair-restoration business in 1999. "I started losing hair when I was young and I knew it could be a big business," says Mr Tham, who has had three hair transplants over the years.

His first transplant took place in a clinic in the English town of Weymouth in 1978 after he saw an advertisement on a train in London.

It was a disaster, he says. The painful procedure was performed by an obstetrics and gynaecology doctor.

"It cost me over £1,000 and the doctor literally pulled hair out and transplanted them back into the scalp. It wasn't properly done and I was bleeding on the train back to London," he says with a mock sigh.

Two decades later, he had another transplant while on a business trip in the US. He started talking business with the doctor of the medical hair institute who offered him a franchise. "He asked for $175,000 to teach two doctors and one nurse for about four months," Mr Tham recalls.

That was how he ended up spending over a million dollars on his hair business. His Hair Harvest clinic was set up in Takashimaya after he sent two doctors - one from Singapore and the other from Shanghai - and two nurses to be trained in the US. "I spent over US$600,000 on their airfares, accommodation and living expenses for four months."

His nightmare began a couple of months later when the authorities introduced a rule banning general practitioners with the Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery degree from carrying out natural hair transplantation. Only dermatologists and surgeons were allowed to do it. He wrote letters and appealed to three health ministers.

To get around the issue, he closed Hair Harvest and set up Hair Synergy and opened two clinics in Shanghai and Guangzhou, where he sent his clients, in 2000.

"Then came Sars (severe acute respiratory syndrome) and the financial crisis. I closed the clinics," says Mr Tham, who chronicled Hair Harvest's battle with red tape in a letter published in The Straits Times Forum page in 2003.

It was not until 2006 that the law prohibiting doctors from doing hair transplants was lifted. "And it's all because of Tham Kwok Onn," he says.

A series of setbacks followed. He spent a big portion of his savings on legal fees in a protracted battle with a Malaysian bank. He was the guarantor for a loan for an agricultural project which went under.

The stress and the death of his youngest son in 2002 sent him spiralling into a pit of despair.

Mr Tham - whose three other children are aged between 29 and 35 - often found himself with the urge to crash his car while driving. By then, he had also wound up some of his businesses, including Eximwood and Exim Fish.

Friends and family rallied around him, but it took three years before he got his groove back. He credits Dr Alex Su, a consultant psychiatrist with IMH, for helping to pull him back from the brink.

When he did, he leapt back into rebuilding his businesses.

Hair Synergy, which offers transplant consultations and referrals to hair clinics in the region, gives him a steady income and keeps him busy. "I want to take it to the next phase," says Mr Tham, who is in talks to buy into HHH, a well-known hair-restoration clinic in Thailand.

He is also often travelling in an attempt to broker real estate deals.

His long-time friend, Dr Tong Thean Seng, says Mr Tham does not always take no for an answer. "He's like that, he will just continue trying."

Retired shipping executive Hwee Mun Lock, 74, who has known Mr Tham since he was seven, agrees.

"Kwok Onn could have and should have achieved more if Luck had been kinder to him. But for him now, it's not a question of getting more money. He's always had tenacity and purpose and he's working towards his dreams. And he's not bitter - he just takes life as it is."

Indeed, Mr Tham says he has no time to stew in regret. "I don't consider myself a failure. I'm just too ahead of my time," says the entrepreneur, who sold off his semi-detached home in King's Close and now lives in a condominium in Alexandra Road.

While he envies friends who are better off, he does not regret the way his life has turned out. "I still have my spirit and my mind. My happiness is to keep trying for success and live as well as I can."