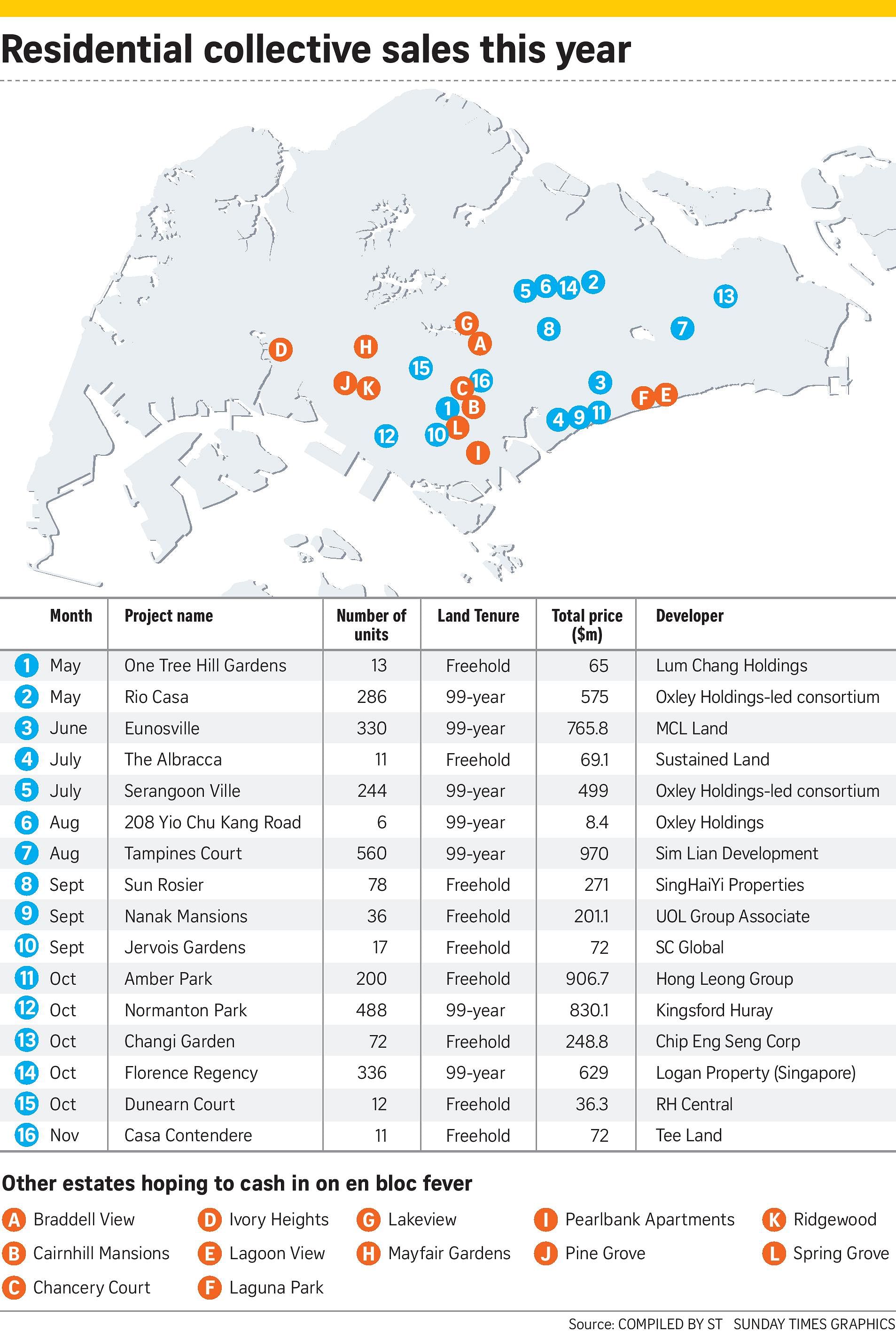

After a quiet decade, since May this year, 16 private residential estates have been put up for sale en bloc, with many others in the pipeline.

In their wake are overnight millionaires, but also displaced communities arising from the changes.

In particular, 2017 spells the end of the road for many Housing and Urban Development Company (HUDC) flats, which have contributed the lion's share of the more than 2,700 private units sold this year.

Even as some celebrate windfalls, the "en bloc" phenomenon has led to worries about infrastructural strains, oversupply of new housing units and class divides, among other things.

But beyond such concerns are also broader questions about the relentless renewal of a city versus the sentimental nostalgia for communities of old.

Insight examines the issues.

WHY THE HYPE THIS TIME?

Analysts predict that this year's frenzy will spark another cycle similar to the 2005-2008 one, which saw many large sites in prime districts sold collectively, giving a windfall to tens of thousands of sellers.

About 2,700 private homes have been sold en bloc this year - more than four times the 600 units sold last year. The total value of the deals has already exceeded $6 billion, with the possibility of even more deals closing by the end of the year. This makes 2017 the third biggest year for such deals in terms of value, after 2007 ($11.7 billion) and 2006 ($9.3 billion), according to Savills senior director research Alan Cheong.

On Monday in Parliament, National Development Minister Lawrence Wong offered two reasons for the pick-up - the first time he has spoken on the subject.

First, developers are keen to replenish their land banks, which observers say have dwindled to low levels since 2007.

Mr Wong had noted a "healthy increase" in the sale of new units in the first three quarters of the year, which in turn translates into unsold supply levels coming down. There are currently 17,200 unsold units, down from 40,000 in 2012, he said.

In addition, buying land through collective sales provides more variety of sites for developers than the government land bank alone - the supply of which developers have complained is insufficient, says veteran developer and academic Steven Choo.

For example, developers can get their hands on plots as small as the 1,313 sq m site on which the six-unit 208 Yio Chu Kang sat, or as large as the 61,408 sq m Normanton Park.

Local developers, in particular, stand a better chance of building up their land reserves this way, since foreign firms are unlikely to stomach the uncertainty that comes with the often-lengthy wait of clearing a sale, he says.

Of the 16 residential sales en bloc this year, only two, both last month, went to foreign firms: Chinese developer Kingsford Huray with the 488-unit Normanton Park at $830 million, and Hong Kong-listed Logan Property's 366-unit Florence Regency for $629 million.

A second reason for the pick-up is that successful sales last year may have encouraged more owners of ageing estates to initiate the process this year to monetise their assets, Mr Wong says.

Cautionary notes about buying properties with expiring leases may also have caused owners of such homes to feel anxious.

In March, Mr Wong directed a blog post to owners of Housing Board flats saying that all leasehold properties will eventually go back to the state on expiry.

In June, the residents of 191 private terraced houses in Lorong 3 Geylang became the first home owners to be told that the authorities will take back their land at the end of the lease - Dec 31, 2020 - and that no lease renewal will be considered.

THE HUDC FACTOR

While it remains to be seen whether developers have the financial clout to redevelop large HUDC sites like Pine Grove or Braddell View this time round, it seems that the end of HUDC estates is nigh.

Of the 18 HUDC estates built, 12 have been sold, with five of these deals - Rio Casa, Serangoon Ville, Eunosville, Tampines Court and Florence Regency - completed this year, the most in any year.

The remaining six - Ivory Heights, Pine Grove, Laguna Park, Chancery Court, Braddell View and Lakeview - are at various stages of the collective sale process.

The HUDC scheme started in 1974 was aimed at those seeking something better than typical HDB flats and ceased 10 years later due to waning popularity. By then, 7,731 units had been built. A decade later, the authorities moved to allow such estates to be privatised.

WEIGHING THE COSTS

Selling units en bloc has its critics, though. As retired businesswoman Poonam Bhandari, 60, wrote in a letter to The Straits Times: "Not everyone is willing to disrupt their lives for a few extra dollars (which they may or may not see eventually). If people want to encash and sell their properties and homes, they should do so on their own, and not subject others to it lest we all feel like displaced insecure refugees in our own country under the guise of urban rejuvenation."

Indeed, despite the influx of cash entering the market from this year's sales alone, a common worry is that sellers may not be able to buy a home of similar size in the same location without topping up - thus eliminating any gains.

Indeed, the average value of each property for sale in this round is closer to $2 million, against $3 million in the last round, when several properties were in prime spots like Ardmore Park, Grange Road and Newton.

International Property Advisor chief executive Ku Swee Yong believes that many sellers then were likely to be foreigners or investors who would have plonked the cash into other investment properties.

But many current owners are locals moving out of their primary - if not only - property, he says.

"Those selling en bloc today aren't going to think about trading up - some of them might even buy an HDB flat and keep the rest of their money for retirement," he says.

While this is not a bad thing, the Urban Redevelopment Authority has already warned that there is a slew of private apartments coming on the market in the next one to two years - about 9,300 units from redeveloped sites alone.

Coupled with the remaining 7,400 units from awarded government-issued sites, there could be a supply of about 16,700 units - double of what is available now.

In a statement to The Sunday Times, the URA notes a "high vacancy rate of 8.4 per cent", or 30,000 empty homes, in the private housing market.

-

WHAT IT TAKES TO GO EN BLOC

-

STEP ONE: A pro tem committee is set up to garner interest in selling en bloc. They must get approval from at least 25 per cent of the owners or 20 per cent of share value to trigger an extraordinary general meeting to determine whether a collective sales committee should be formed. If it is their second attempt within two years, this is bumped up to 50 per cent, and to 80 per cent for subsequent attempts.

STEP TWO: Once the sales committee is set up, it will seek professional advice from lawyers, marketing or property consultants and obtain an independent valuation report. These professionals also have to advise on the proposed method of distributing sales proceeds.

STEP THREE: Owners must then sign a collective sale agreement. If the property is more than 10 years old, the owners of 80 per cent of the share value or land share must agree in writing. If it is younger, the threshold is 90 per cent.This must be done within a year or the sale is rendered invalid. A failed bid will trigger a two-year restriction on another collective sale attempt.

STEP FOUR: The property is placed on the market.

STEP FIVE: Once a buyer has been found, an application can be made to the Strata Titles Board, which will decide if the sale can go through. Owners who do not agree to the sale can still raise their objections with the Board.

Rachel Au-Yong

It also notes the potential strain the significant increase in dwelling units may bring to existing road networks and local infrastructure.

Says a spokesman: "Before any planning approval can be given, the developers have been asked to undertake an assessment of the traffic impact and identify feasible transport improvement plans and/or traffic demand management measures. This may include reducing the proposed number of dwelling units."

Beyond the physical strain on the environment, there is also the loss of communities.

Mr Ku is concerned that the culture of frequent redevelopment may result in a streetscape that changes often, or worse, lead to "communities that are not resilient because nobody knows each other".

But NUS sociologist Tan Ern Ser points out: "They can still keep in touch via group chat, and given that Singapore is a small island, it'd still be easy to meet up regularly. Better still, they can make a decision to continue staying near one another."

Another under-discussed upside is how the latest round of collective sales essentially removes many HUDCs from the housing market. NUS urban sociologist Ho Kong Chong notes that executive condominiums are taking their place. These are, increasingly, being planned to enable more social mixing by having them "embedded in HDB new towns, only that they come with fences and fancy amenities".

The next step, he adds, is to have more open condos. This is already in the works - last month, the URA announced it will explore a mix of low gating and transparent barriers in condos in three towns.

"In a way, HUDCs are more exclusive than ECs because they are stand-alone estates, while it's hard to ignore that ECs are right smack in a HDB new town," he says.

And while some critics of collective sales lambast how environmentally unfriendly it is to tear down an otherwise functioning building, most observers say the potential to redevelop large but under-utilised plots is the right thing to do.

JLL national director for research and consultancy Ong Teck Hui similarly argues that there is "no heritage value" to preserving HUDC estates, which are "generally ageing and under-utilising the plot ratios of their sites."

"It might be better to redevelop the under-utilised site than to release fresh sites to provide the needed supply given our limited land resources," he adds.

By and large, observers agree that developers' desire for collective sales reflects vitality - which in turn drives urban renewal.

"If people can't redevelop, maintenance will break down at some point, and the housing stock deteriorates," says Dr Choo. But he also wonders if the hype may build up into a bubble further down the road.

Correction note: This story has also been edited to reflect clearly that the higher thresholds needed to trigger a meeting to determine whether a collective sales committee should be formed kick in only if an estate wishes to conduct subsequent attempts after a failed try within two years.