"Seven people stood waiting for an elevator in a hotel lobby. One of them coughed. Within hours, a few of them had flown halfway across the world. Within days, three of the seven people were dead, including the man who coughed. That, according to epidemiologists, is how severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars) spread from Hong Kong to the world".

Although it reads like a screenplay for a horror movie, this unfortunately is a true depiction of the key event which led to the global spread of the Sars pandemic more than 10 years ago.

The global Sars outbreak claimed more than 700 lives in countries worldwide, including Singapore. It also taught us a heavy lesson about what devastation a previously totally unknown virus can cause to our "global village", made possible with ever-improving transport systems.

Despite the significant improvement in our preparedness to respond to outbreaks, like Sars in Singapore and internationally, the recent outbreaks of Ebola in Africa and Middle East respiratory syndrome (Mers) highlight the need to be vigilant at all times.

In Singapore, annual dengue virus outbreaks and other infectious diseases (such as hand, foot and mouth disease) further remind us that the fight against infectious diseases is a never-ending journey. We need constant improvement in every aspect required, from infrastructure and research to policy and international collaboration.

I was trained as a biochemist for my PhD at the University of California, and had the good fortune to conduct research on many new and emerging infectious diseases when I was with the Australian Animal Health Laboratory. This included work on the Sars, Hendra, Nipah, Melaka, Mers and Ebola viruses.

From my over 20 years of work experience, I have found that infectious disease outbreaks behave more like enemies during traditional warfare: They attack very rapidly, can cause immense damage within a short period and their progression is unpredictable. Moreover, each outbreak varies from previous ones. So, in order to win the war, it is absolutely important that we do all the groundwork during peacetime.

-

About the writer

-

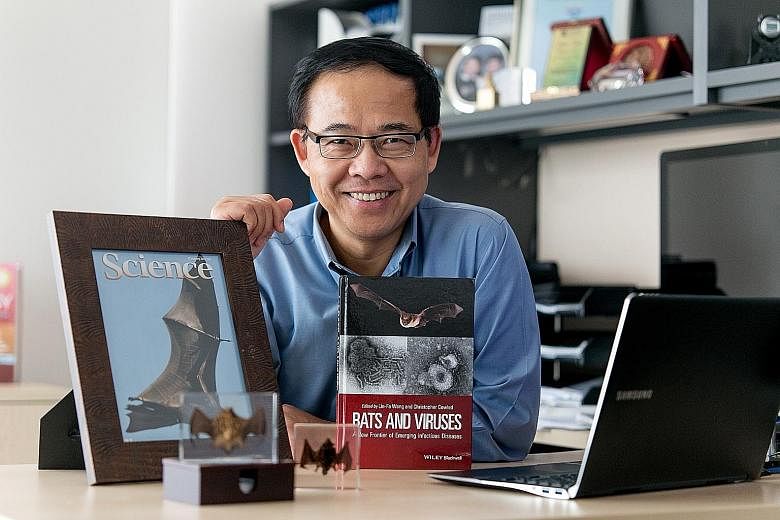

Professor Wang Linfa, 55, is the director of the emerging infectious diseases programme at Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School Singapore. He is also an honorary professor at the University of Melbourne and Chinese Academy of Sciences.

He completed his bachelor's degree in 1982 at the East China Normal University in Shanghai, and obtained his PhD at the University of California, Davis, in the United States.

His early research was done in Australia's Monash Centre for Molecular Biology and Medicine. In 1990, he joined the country's Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation's Australian Animal Health Laboratory, where he played a leading role in identifying bats as the natural host of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars) virus.

Recently, he led an international team that carried out comparative genomic analysis of two bat species. It discovered an important link between bats' adaptation to flight and their ability to counter DNA damage as a result of their fast metabolism, and also to co-exist with a large number of viruses without developing clinical diseases.

Prof Wang's work has been recognised internationally; he has received numerous international awards, given speeches at major international conferences and published in top scientific journals, including Science, Nature Reviews Microbiology and the Proceedings Of The National Academy Of Sciences. He has also contributed to five patents and written many book chapters.

Unfortunately, this is easier said than done. Groundwork for building capacity to fight infectious disease outbreaks requires government support for funding and infrastructure building; long-term planning for training basic researchers and clinicians who are dedicated and specialised in dealing with fighting unpredictable infectious disease events of unknown origin; and strong and transparent communication and collaboration across borders in the international community.

Despite all these challenges, I am convinced that the international community as a whole has made substantial progress since the devastating Sars outbreaks in the early 2000s. Singapore, along with China and several other nations in the region, has made changes in improving our capability to respond to future infectious disease outbreaks.

One example was the establishment of the Programme in Emerging Infectious Diseases (EID) at Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School Singapore (Duke-NUS). Since its inception in 2008, the programme has recruited 12 tenure-track and seven research-track principal investigators conducting internationally competitive research in the infectious disease field.

I had the privilege of taking over the directorship of the EID programme at Duke-NUS in July 2012. My philosophy is as follows: our nation's success during "wartime" will be determined by our efforts during "peacetime". As a programme, our emphasis is therefore on basic research, which provides the basis to support an effective offensive.

Our research activities include pathogen discovery and improving diagnostics, better understanding of risk factors triggering major infectious disease outbreaks, better understanding mechanisms of pathogenesis, development of novel vaccines and therapeutics, and conducting clinical trials with our clinician collaborators to make a real impact on our nation's public health system.

Over the years, our programme has trained more than 20 PhD students and more than 60 research fellows - some of whom have already started their own careers as future leaders in this area. There have been three spin-off biotechnology companies founded by programme faculty members. The programme also spawned three clinical trials of novel therapeutic and vaccine strategies in fighting dengue and other infectious diseases. We have been able to translate research done at a molecular level to tangible treatment which may be able to help Singapore cope with its dengue burden.

This year has proven to be a very important and successful year for the programme. Two of our faculty-led studies were published in the same issue of Science - findings from one of them bring us closer to a viable dengue therapeutic, while the second helps us better understand dengue's viral genome. Another of our faculty found that Hepatitis B infection exposure increases the immune system maturation of infants. This is a paradigm shift in the approach to treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis.

I have been nicknamed "Bat Man", (actually, the "Bat Virus Man", to be more accurate!) in the international emerging infectious diseases research field because I have been conducting research into bat-borne viruses for the last two decades.

More recently, my research focus has been on the mysterious relationship between bats and many of the killer viruses, including Sars, Mers and Ebola.

A book that I co-edited - released last Friday - Bats And Viruses: A New Frontier Of Emerging Infectious Diseases, is an important milestone, considering that a similar one on this topic was last published in 1974.

It is now thought that 75 per cent of all emerging human infectious diseases originate in other animals, and bats are being increasingly recognised as one of the most important reservoirs for emerging viruses. In addition to Sars and Ebola, bats are implicated as the source of diverse human pathogens, including Nipah, Hendra, Marburg virus and Mers.

I hope that this book will be useful reference for bat researchers studying microbiology, virology and immunology, as well as infectious disease workers and epidemiologists.

We are not safe yet from further infectious disease threats. Our efforts during "peacetime" will be the key to determining how successfully we can respond to outbreaks in the future.