Holding a fork or a spoon is painful, and walking a short distance causes painful blisters to form on the soles of the feet.

It is unthinkable, but this is what children suffering from epidermolysis bullosa (EB) - a rare genetic skin-blistering condition, have to go through in the course of their daily lives.

Those afflicted are called "butterfly children" because of how fragile their skin is, in the same way that butterflies have fragile wings. The congenital condition prevents skin layers from bonding (see other report).

It affects children in at least 30 families here.

Children with the condition develop big blisters on various parts of their body. The blisters have to be broken and then drained before they are wrapped up in bandages.

-

About the disease

-

Q What is epidermolysis bullosa (EB)?

A It is a congenital skin-blistering disease.

Babies who inherit the condition are born with skin that is unable to withstand the everyday stress of rubs and knocks, said Dr Ng Yi Zhen, research fellow at the Epithelial Biology Lab of the Institute of Medical Biology (IMB) at the Agency for Science, Technology and Research.

The disease affects more than 30 families in Singapore and an estimated half a million people worldwide.

There is currently no effective therapy and cure for EB.

There are three main types of EB, with the most common form being EB simplex, which Dr Ng and other researchers at IMB are studying.

Dr Ng said EB simplex is mainly caused by inherited mutations in genes of keratin 5 and keratin 14. Keratin 5 and 14 are filament proteins, which make microscopic supportive mesh-like networks within skin cells.

These keratins are responsible for the ability of our skin to withstand mechanical stress, such as rubbing and pinching. Mutations in these keratins result in fragile skin, said Dr Ng.

Dr Mark Koh, head and consultant of Dermatology Service at KK Women's and Children's Hospital, said EB simplex is a less severe form of EB and patients can usually lead near-normal lives.

The severe forms of EB, such as junctional EB, can lead to death in infancy or early childhood. "Most patients who die from EB suffer from severe forms of EB, and the cause of death is usually severe infection," said Dr Koh.

-

Carolyn Khew

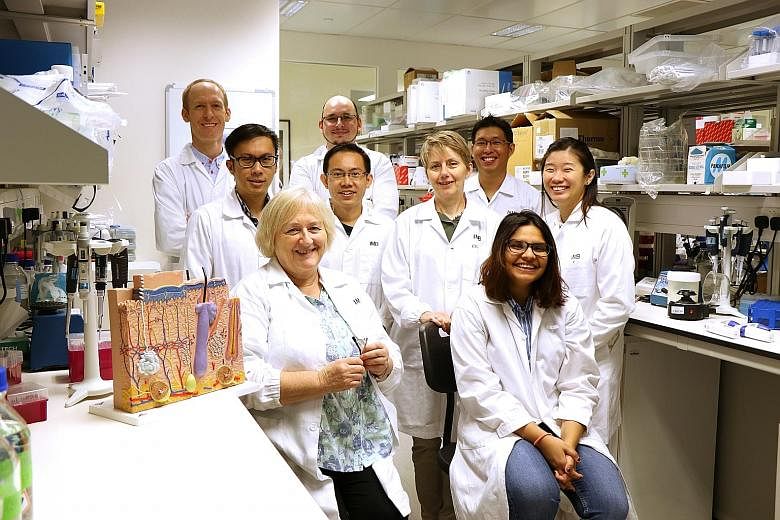

"It's most prominent with the children because they have very fragile skin," said Professor Birgitte Lane, executive director of the Agency for Science, Technology and Research's (A*Star) Institute of Medical Biology (IMB). She is the principal investigator of IMB's Epithelial Biology Laboratory.

"They are covered in sores most of the time because the skin just comes off. Almost every single action that they do in normal life is going to cause them pain unless they are very careful with their skin," she said.

There is currently no treatment for the rare condition, but researchers at A*Star hope their work will eventually come up with a drug for the disease.

Prof Lane, a skin specialist known for her work on keratin proteins and genetic skin conditions, is working with other scientists to find ways to treat these diseases.

In particular, the IMB scientists are studying EB simplex - which accounts for about 70 per cent of all EB cases in Singapore.

In their lab, the scientists have made skin cells that carry the gene causing the blistering disorder, and are using these cells to search for compounds that may improve the resilience of these disease cells. So far, more than 100 drugs and compounds have been tested.

Prof Lane said the lab is now focusing on a handful of drugs that are showing promising results for EB simplex.

"In these early stages, we cannot predict which drugs will be suitable for testing on the patients. There are many stages of testing safety and efficiency in the laboratory before the drugs can be tested on patients," added Prof Lane.

The team hopes to start clinical trials soon and this will most likely take place in collaboration with hospitals overseas.

Since the 1990s, as many as 18 causative genes have been identified, leading to improvements in the diagnosis of EB.

Dermatologist Lynn Chiam from the Mount Elizabeth Novena Hospital said studies are under way to find better ways to treat and relieve the symptoms of EB.

These include bone marrow transplants and other treatments that can help blisters and wounds to heal faster.

"Some therapies under study may also lead to a marked reduction of blisters and improved quality of life," added Dr Chiam.

Student Ira Jain, who suffers from EB, said any treatment that strengthens the skin would help improve her quality of life.

The 17-year-old, who does the International Baccalaureate Diploma Programme at St Joseph's Institution, did an internship at IMB in January last year. She learnt about the genetic reasons for her skin condition and how to grow human skin cells in vitro.

"EB patients are usually not able to walk more than very short distances without blistering on the soles of their feet. The heat and humidity make this condition doubly worse," said Ira. On hot days, she is unable to walk more than 50m.

"Any treatment that strengthens the skin would delay the formation of blisters and extend the range of my mobility. I would be more able to walk around and run as I would not have to focus on when I should stop."