-

839

The number of people who died in Brazil last year from the tropical disease.

628

The number of dengue cases in Singapore last week. This is the highest for the month so far.

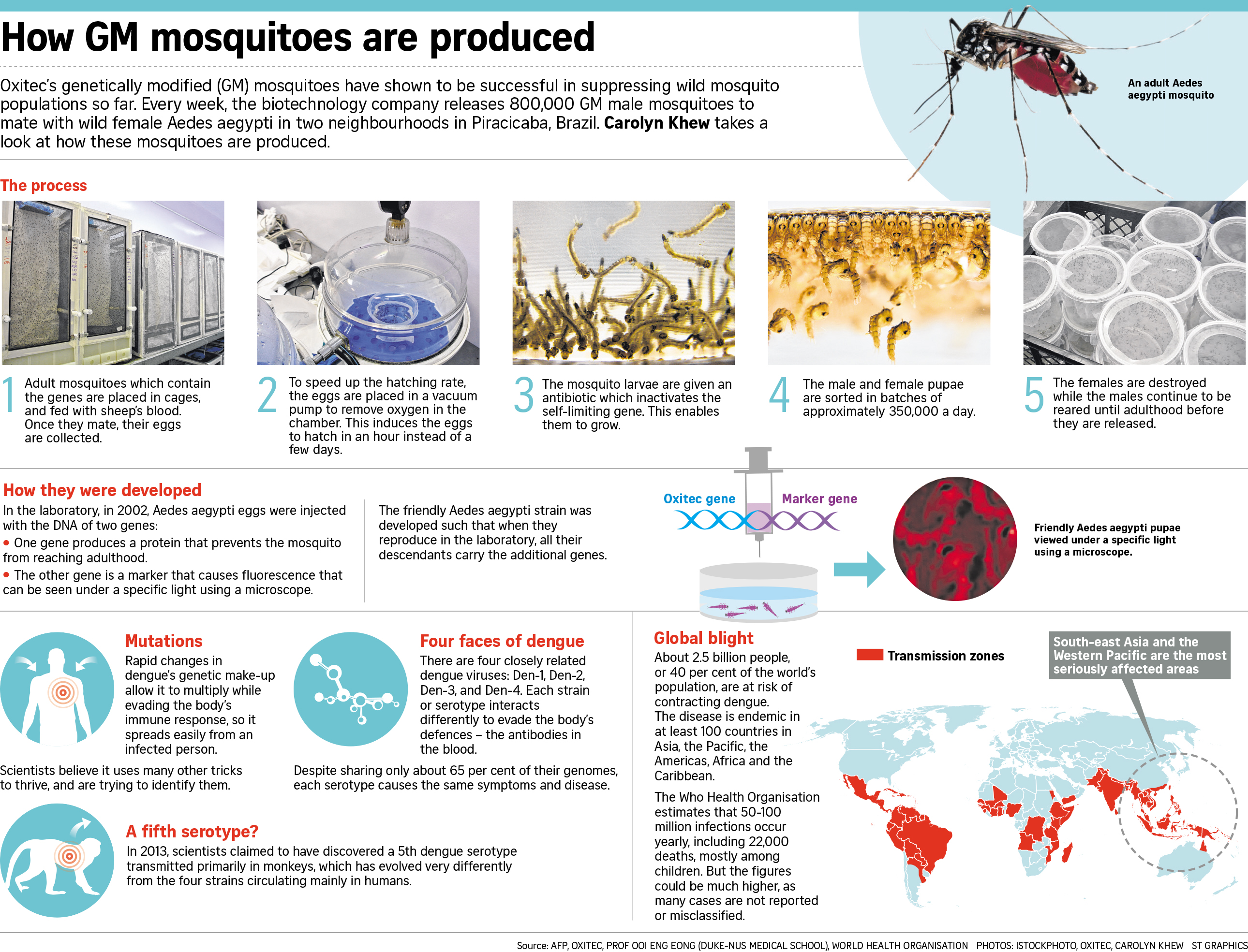

Fighting dengue with genetically modified mosquitoes

Oxitec's special mozzies have a self-limiting gene that kills off larvae

It sounds crazy, but biotechnology company Oxitec has been breeding and releasing millions of mosquitoes in dengue hot spots, to keep the deadly disease in check.

Its plan seems to be working.

To suppress the wild Aedes aegypti mosquito population responsible for dengue outbreaks, British company Oxitec has created special mosquitoes of the same species which have a self-limiting gene that kills off their larvae (see graphic).

The project started in April last year, and about 800,000 of these mosquitoes are released every week into the neighbourhoods of Cecap and Eldorado in the eastern part of the Brazilian city of Piracicaba.

Five times a week, pots of insects are loaded onto a van and released in specific places mapped out on a route, including the bus terminal and residential areas.

"Dengue is a persistent problem. Everyone knows someone who has had dengue before and they also know that everything which has been done in the past hasn't solved the problem," said Mr Glen Slade, director of Oxitec do Brasil (Oxitec's Brazil company).

Previous methods of controlling the mosquito population, such as using pesticides and getting rid of breeding sites, have had limited success, and that was what prompted the authorities to give this method a try, said Piracicaba's municipal Secretary of Health Pedro Mello.

"The way we have been trying to fight dengue has been the same for the past 100 years," Dr Mello told The Straits Times. "It was almost impossible to control dengue using those methods. These mosquitoes have adapted well to living alongside us humans."

Dengue cases have soared in Brazil, with the climate and population density ideal for mosquitoes to breed and dengue to spread. An infected mosquito can spread the disease to a person with just one bite.

Dr Mello pointed out that the Aedes aegypti mosquito had developed resistance against pesticides like DDT and pyrethroids, so using the same type of pesticide is not viable.

Moreover, mosquito eggs can lie dormant for up to a year until conditions are right for them to hatch.

While the plan to release the special mosquitoes received some scepticism from civic groups and residents at first, it seems promising so far.

On Tuesday, the company and Piracicaba City Hall said in a statement that the number of wild larvae produced by the Aedes aegypti mosquito collected from traps in the treated areas was 82 per cent lower than the number from a control, non-treated area in just nine months.

The company has been monitoring the results of the project by collecting larvae from 95 ovitraps placed in the district.

As the genetically modified (GM) mosquitoes also contain a marker gene which shows up under special filters, researchers are able to tell the wild larvae from those that are the offspring of Oxitec's mosquitoes.

City mayor Gabriel Ferrato has announced that the project in the district would be extended for another year. And a letter of intent has been signed to expand it to the city's central area.

"In the case of the Aedes aegypti, we looked for the tool that seemed most appropriate in the tough battle against this mosquito that transmits dengue, Zika and chikungunya," said the mayor.

Like dengue, chikungunya causes fever and joint pain but is usually not fatal. The Zika virus can cause fever, rash and joint pain, with symptoms usually lasting under a week, but it has caused panic in the Americas recently because of its link to microcephaly. This condition causes infants to be born with smaller heads and brain damage.

The Piracicaba project is working well now, but it took two months of public engagement to help residents understand the GM insects.

Community health agent Madlaine Teixeira, 51, who was involved in the effort along with Oxitec staff, said they had to explain what the mosquitoes were and how they do not transmit diseases.

"At that time, the rate of dengue was really high and residents were asking why are you releasing more mosquitoes when we want to get rid of them?" said Mrs Teixeira, who has worked as a health agent in the city for 16 years. "It took a lot of hard work but now they trust the idea and even welcome the mosquitoes."

Last month, Brazil also became the first South American nation to authorise the world's first dengue vaccine manufactured by French pharmaceutical giant Sanofi Pasteur.

Dengue cases are also going up worldwide, with the World Health Organisation (WHO) calling it the most rapidly spreading mosquito-borne viral disease. There has been a 30-fold increase in global incidence over the past 50 years and WHO estimates that 50-100 million dengue infections occur each year.

In Singapore, the number of dengue cases has been going up again, with 628 cases from Jan 10-16, and the authorities say that a change in the main strain of virus, from Den-1 to Den-2, "may be an early indicator of a future dengue outbreak".

According to reports, the disease killed 839 people in Brazil last year and infected more than 1.5 million.

But the two Oxitec test cities have seen just one case of dengue since July last year, compared to 133 in the period, July 2014-July 2015.

The WHO said that new methods, including lethal ovitraps, GM mosquitoes and Wolbachia-infected Aedes, could play a "significant role" in long-term dengue prevention. Wolbachia is a bacterium which can be found in many insects, and when Wolbachia-carrying male mosquitoes mate with wild females, the females produce eggs which do not hatch.

For Ms Vanessa Mello, 35, the GM mosquitoes have proven their worth. The sales assistant contracted dengue last March, but she hasn't heard of anyone in her neighbourhood who has caught the disease since the project started last April.

"Dengue was terrible. I had a headache and pain in the eyes... Having so many mosquitoes around is a little bit annoying but if it's for the public good, why not?" she said.

Join ST's WhatsApp Channel and get the latest news and must-reads.

A version of this article appeared in the print edition of The Straits Times on January 22, 2016, with the headline Fighting dengue with genetically modified mosquitoes. Subscribe