SINGAPORE - A major project that aims to free up space on land by moving facilities for treating used water underground is under way, with about a quarter of a 100km-long conveyance system for central and western Singapore completed so far.

The $10 billion Deep Tunnel Sewerage System (DTSS), which is scheduled for completion by 2025, will be one of the nationally significant infrastructures that the Government intends to pay for through borrowing - something that has not been done since the 1990s.

The Bill for the proposed Significant Infrastructure Government Loan Act (Singa), which was introduced earlier this month, will allow the Government to borrow up to $90 billion to pay for infrastructure that will last for at least 50 years.

This means the cost will be spread out over many years, with each generation that benefits bearing part of it.

"The DTSS is an example of how Singapore builds long term. This can actually last us for the next 100 years, so effectively we're building in this generation for the next generation, and the generation after that," said Ms Indranee Rajah, Second Minister for Finance, during a site visit to DTSS Phase 2 (DTSS 2) on Monday (April 19).

She was joined at the event by Ms Grace Fu, Minister for Sustainability and the Environment.

DTSS is essentially a network of deep tunnel sewers that makes use of gravity to channel used water to three centralised treatment plants, where the water is purified to produce Newater.

The project was conceived more than two decades ago to improve Singapore's water resilience, as the system will allow the Republic to better capture every drop of water for reuse.

When the DTSS is ready by 2025, intermediate pumping stations and conventional water reclamation plants will be phased out, freeing up about 214 football fields' worth of land.

Addressing water and land scarcity

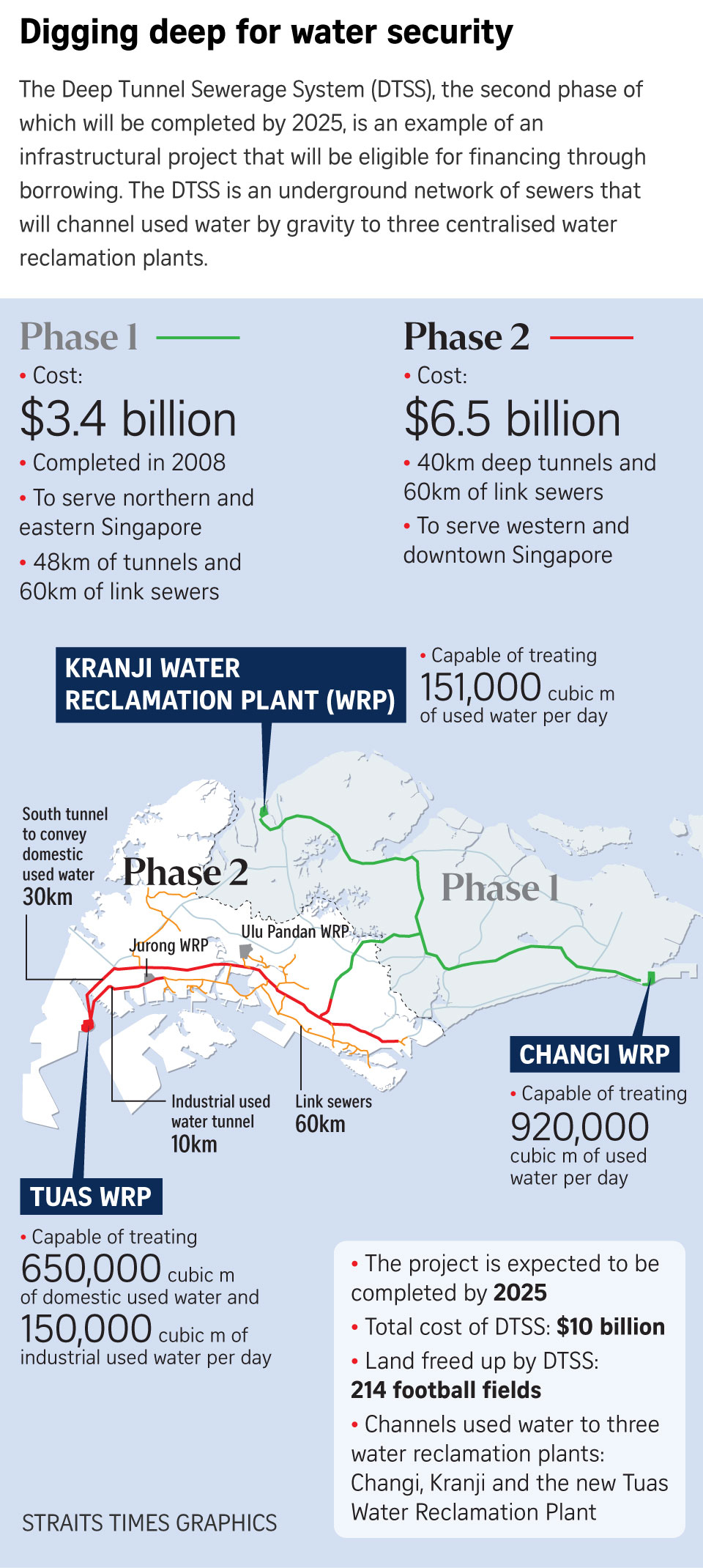

Construction of the DTSS is being done in two phases.

The first phase, which involved more than 100km of tunnels and link sewers serving the northern and eastern parts of Singapore, was completed in 2008 and cost $3.4 billion.

Three conventional water reclamation plants in Kim Chuan, Bedok and Seletar were phased out following the completion of the first phase and the land they sat on was made available for other developments.

Used water was instead channelled to Changi Water Reclamation Plant in the east and the Kranji plant in the north.

Construction for phase two, which will channel used water from the downtown and western parts of Singapore to the new Tuas Water Reclamation Plant, began in 2017.

As at April this year, about 24km of the 100km-long conveyance system for phase two has been completed.

Once in place, land for conventional water reclamation plants in Ulu Pandan and Jurong will be freed up, as will the plots now being used for immediate pumping stations.

The second phase is estimated to cost about $6.5 billion.

Financing projects for the future

Singapore last borrowed for infrastructure in the 1970s and 1980s to pay for the large upfront costs of building Changi Airport as well as the Republic's first MRT lines.

By the 1990s, with the economy growing rapidly, the Government paid for infrastructure in full from its revenue.

The country now faces another hump in its development spending needs, with plans for new rail lines and coastal protection measures against rising sea levels.

This comes amid a tighter fiscal situation, exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Singapore is expected to record a Budget deficit of $64.9 billion in the 2020 financial year, and is expecting to record another deficit of $11 billion in the 2021 financial year.

But there are measures in place to ensure fiscal prudence.

For instance, only certain "nationally significant infrastructure" can be funded under the proposed Singa law.

This refers to infrastructure that supports national productivity or Singapore's economic, environmental or social sustainability.

Examples include major highways, structures to supply, recover and treat water, and coastal protection measures.

Such infrastructure must last for at least 50 years so as to benefit multiple generations.

It must also be owned by the Government and be controlled by it, or on its behalf. Another criterion is that the expected cost of the infrastructure project should be at least $4 billion.

The Bill will be further debated in May.