MASSACHUSETTS • Small rocks from the beaches of eastern Massachusetts began appearing at Lexington High School last autumn. They were painted in pastels and inscribed with pithy advice: Be happy... Mistakes are OK... Don't worry, it will be over soon. They had appeared almost by magic, lifting spirits and spreading calm at a public high school known for its sleep-deprived students. Crying jags over test scores are common. Students say getting Bs can be deeply dispiriting, dashing college dreams and profoundly disappointing parents.

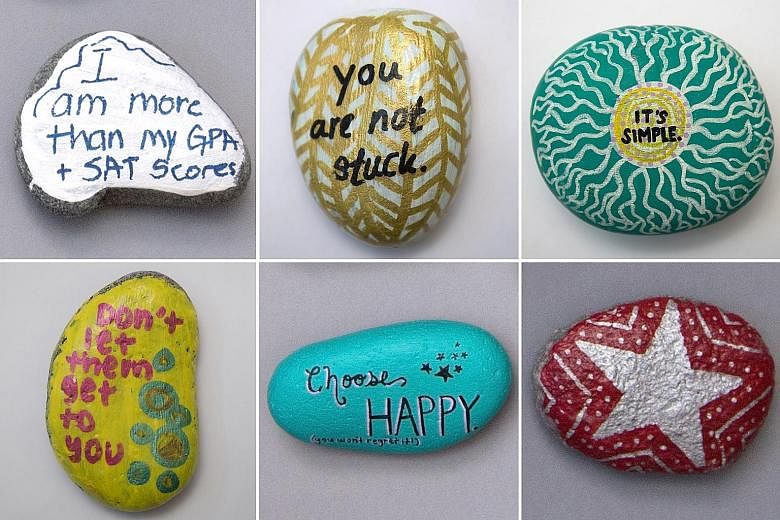

The rocks, it turns out, were the work of a small group of students worried about rising anxiety and depression among their peers. They had transformed a storage area into a relaxation centre with comfy chairs, a lava lamp and a coffee table brimming with donated art supplies and lots and lots of rocks - to be painted and given to favourite teachers and friends. They called it the Rock Room.

"At first it was just us," said senior Gili Grunfeld. "Then everyone was coming in." So many rocks were piling up, they had to be stored in a display case near a cafeteria. The maxims seemed to call out to students as they headed to their classes in conceptual physics, computer programming, astronomy and advanced placement music theory.

And they became a visual reminder of a larger, community-wide initiative: to tackle the joy-killing, suicide-inducing performance anxiety so prevalent in turbocharged suburbs like Lexington. In recent years, the problem has spiked to tragic proportions in Colorado Springs, Colorado; Palo Alto, California; and nearby Newton, Massachusetts, where stress has been blamed for the loss of multiple young lives. In January, a senior at Lexington High School, who had just transferred from a local private school, took her own life.

Residents in this tight-knit hamlet are hoping to stem the tide. Ms Mary Czajkowski, the district superintendent, was hired in 2015 with the mandate of "tackling the issue head on". Elementary school pupils now learn breathing exercises and study how the brain works and how tension affects it. New rules in the high school limit homework. To decrease competition, there are no class rankings and no valedictorians and salutatorians. In town, there are regular workshops on teen anxiety and college forums designed to convince parents that their children can succeed without the Ivy Leagues. Last October, more than 300 people crammed into the town hall for a screening of Beyond Measure, a sequel to education advocate Vicki Abeles' documentary on youth angst, Race To Nowhere.

Ms Claire Sheth, a mother of four who had invited Ms Abeles to town, described Lexington students as "tired to the core". Students say depression is so prevalent it affects friendships, turning teenagers into crisis counsellors. "A lot of kids are trying to manage adult anxiety," said principal Laura Lasa.

The problem is not anecdotal. In a 2015 national health survey, 95 per cent of Lexington High students reported being heavily stressed over their classes and 15 per cent said they had considered killing themselves. Thinking about it most often were Asian and Asian-American students - 17 per cent of them, as is the case across the United States.

The town's growing Asian community has not been timid in acknowledging the problem. Through college forums and chat rooms, parents and leaders of the Chinese- American and Indian-American associations have been working to lower the competitive bar and realign parental thinking. Others are pushing back. They don't want the workload reduced - they moved here for the high-rigour schools. At association meetings, where the tension is most pronounced, discussions about academic competition have brought some to tears.

Indeed, reversing the culture is complicated in a town that prides itself on sending dozens of students to the Ivy Leagues: 10 went to Harvard last year and seven to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Young people are lauded at school board meetings and online for publishing academic papers or performing at Lincoln Centre. Last year, the varsity team placed second in the 2016 History Bowl nationals and fourth in the National Science Bowl. The robotics team has qualified for the FIRST Championship, an international technology and engineering competition, for five of the past six years.

After school recently at the public library, which was packed with students poring over textbooks, calculus work sheets and term papers, a sophomore looked up from her world history textbook and said: "You see all these people? They want the same thing - that's really overwhelming." What they want: Entry to a top college when acceptance rates are at an all-time low.

LEXINGTON looks and feels like a lot of other affluent suburbs: serene, stately, with a whiff of muted money. Minivans and ageing Volvos are packed with violins and soccer gear. There are meticulously restored Colonials and Tudor revivals. Walk along the red brick sidewalks of Massachusetts Avenue, which cuts through the centre of town, and Lexington's Brahmin past is evident: a statue on the Battle Green of a musket-toting Captain John Parker, who led the fight against the British in 1775.

In evidence as well are signs of the burgeoning biotech industry and the changing face of America's elite.

Since 2000, the Asian population has ballooned from 11 per cent to an estimated 22 per cent of Lexington's 32,000 or so residents. Today, more than a third of its students are Asian or Asian-American.

In the Crafty Yankee or the Asian bakery, you are likely to bump into electrical engineers from Seoul, physicists from Beijing and biochemists from Boston. They teach at Harvard (16km away) and run labs at MIT (18km). They hold top posts in the pharmaceutical companies that dot the Boston-area tech corridor. More than half of the adults in Lexington have graduate degrees. And many want their children to achieve the same.

In many ways, Lexington students are the by-product of the self-segregation that Enrico Moretti writes about in his book, The New Geography Of Jobs, which addresses the way well-educated, tech-minded adults cluster in brain hubs. For their children, that means ending up in schools in which everyone is super bright and hypercompetitive. It's hard to feel special.

Best-selling authors and child psychologists have long urged parents to divest themselves from their child's every accomplishment, thereby sending the message that mental health matters more than awards. In Lexington, the attack is more comprehensive, involving schools, neighbourhoods, churches and synagogues. It is riffing off research showing that resilience and happiness, reinforced by the entire community, can be just as contagious as stress and depression.

"You need to bring along everybody," said Ms Abeles, whose campaign has taken her to towns with similar communitywide efforts, including Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, and New Rochelle, New York.

Associate dean for research Peter Levine of the Jonathan M. Tisch College of Civic Life at Tufts said communities that bond to promote pro-social behaviour can be powerful inoculators for youth. "Family problems are often community problems," he said. "They need community solutions." No one is more aware of this than Ms Lasa, who grew up here, earned degrees from nearby Springfield College and Lesley University, and then returned to the district - watching all the while as the population morphed from relatively laid-back to Type A. She often wakes to emotional e-mails from parents sent to her inbox after midnight. Most are about their children's academic standing, and the tone is often disappointment.

Last autumn, as 557 bright-eyed freshmen gathered for orientation, she gave a speech that over the past few years has come to focus more and more on stress reduction. She begged the students to make mistakes. "Do not believe you must acquire straight As to be a successful student," she said. "If you and/or your parents are caught up in society's picture of success, let us help you change the focus."

THE paradox of Lexington High School is that while indicators of anxiety abound, so too does an obsession with happiness.

A banner from the town's newly formed suicide prevention group, a chapter of the national organisation Sources of Strength, greets students as they enter the sprawling red brick building, proclaiming: "Be a Part of Happiness". Students were asked to write down their sources of strength, which were then posted beneath the banner and on Facebook. Some named their pets or friends. One wrote: "My mum." Another: "Trip to Israel!" A girl with green hair: "Chicken curry."

One recent morning, students in "Positive Psychology: The Pursuit of Happiness", a popular elective, were following up on a discussion about psychologist Barbara Fredrickson's "broaden and build" theory, which posits that negative emotions like anxiety and fear prompt survival-oriented behaviours, while positive emotions expand awareness, spurring ideas, creativity and skills.

"Today, we are going to look at pretty simple ways to make it more likely that you experience positive emotions on a day-to-day basis," Mr Matthew Gardner told his "Happiness" students. The class discussed the benefits of exercise and eating foods that release feel-good hormones. The students also learnt that smiling and being smiled at releases dopamine, which has an uplifting impact.

At one point, the class practised laughter yoga, raising their arms slowly as they breathed in, then lowering them as they breathed out, and bursting into peals of laughter. Later, the students recorded changes in their pulse rate to demonstrate research from the HeartMath Institute that shows heart rates slow down and smooth out after bouts of good feeling.

"It's not just that your heart rate goes down and you become very calm," Mr Gardner explained. "It's that the shape of your heart rate is smooth and more controlled. Frustration is more jagged." Their homework assignment: Do laughter yoga or "smile at five people you wouldn't normally smile at".

The district has raised the number of counsellors and social workers, including those working in the elementary schools, and expanded the training they receive in identifying and supporting at-risk students.

Ms Cynthia Tang, whose parents emigrated from Taiwan, has been a counsellor at Lexington High for 12 years. Warm and well-liked, she organises workshops addressing the pressure on Asian students to succeed, borrowing insights from the childhood discord she experienced with her own parents as well as research on biculturalism. Studies show the less assimilated parents are to US culture, the more stressed the children.

Adding to the pressure are cultural differences in how parents, raised abroad, and their offspring, raised in the US, are expected to process setbacks and strife: US educators routinely urge students to share their feelings; not so in Asia. "I see a lot of this being bicultural conflict," Ms Tang said. "When you have one side of the family holding one set of values and the other embracing a new set of values, that inherently creates a lot of misunderstanding and a lot of tension."

The disconnect is compounded by a lack of knowledge about the various routes to success available in the US. Last year, she was brought in by the vice-president of the local Chinese-American Association, Dr Hua Wang, to help plan the college forum, an event on Father's Day. Dr Wang, an engineering professor at Boston University, wanted to shift the focus away from a guide on applying to top colleges.

At the forum, she presented a slideshow celebrating the academic trajectories of respected Chinese-Americans: Fashion designer Vera Wang went to Sarah Lawrence College; Mr Andrew Cherng, who founded the fast-food chain Panda Express, went to Baker University in Kansas; best-selling author Amy Tan, San Jose State University. Parents were surprised. But, Ms Tang said: "I think a lot of parents felt like, 'What do I do with that information?'"

This year, organisers will delve deeper into the differences between the Chinese and US systems, and plan to add another element: a discussion on combating stress. Dr Wang said they want to showcase families who have adopted a more "holistic view" of education. Selected parents of graduating seniors will talk about how they encouraged their children to get enough sleep, comforted them when they came home with Bs and discouraged them from skipping ahead in maths to be eligible for higher-level classes earlier.

This would not be the only time that Dr Wang had engaged in this kind of dialogue. Using the Mandarin words danding, which means to keep calm and steady, and ruizhi, which means wise and far-sighted, he has initiated conversations on WeChat, an online chat room popular among Chinese parents.

Recently, he told them: "Calmness and wisdom from the parents are the Asian child's greatest blessings." But the message was not well received by everyone. Among the responses: "If your child gets a C, how do you get to a point of calm? You think we should be satisfied because at least he didn't get a D?" And: "But my heart still whispers: Am I not just letting my child lose at the starting line?"

Ms Melanie Lin, a parent, found herself in a heated conversation on WeChat after early-admissions decisions arrived last school year. She urged the other parents to stop bragging on the site about acceptance letters to top-tier schools. "If it's only those students who are attending the big-name schools that are being congratulated, then the idea being passed on is that only those students are successful, and attending a big-name school is the only way to become the pride of your parents."

Ms Lin, who works at a pharmaceutical company, emigrated in the 1990s from Beijing to get a PhD in biochemistry from Arizona State University. She said her rebuttal annoyed even close friends, whose online responses accused her of trying to deny parents and their children their moments in the spotlight.

Ms Lin told me: "There is just so much pressure." For her, the struggles are not theoretical. On the home front, she too can be just as obsessed as her peers. Her daughter, Emily, would agree. During junior year, she dreaded car rides and family dinners - any time she was alone with her parents - because conversations routinely veered back to college. Now a senior, Emily has eight AP (advanced placement) and 13 honours classes under her belt. She is also a violinist, choral singer, competitive swimmer and class vice-president.

For a chunk of her high school years, Emily was one of those who "isolated for academics", working into the early morning hours on homework and waking up, sometimes before dawn, after only five or so hours of sleep. She skipped birthday parties and lunch to squeeze in more studying. "I was never doing anything for pure fun," she said. "I put my head down, and I was always running somewhere with some purpose." But as a member of a youth board for a teen counselling centre in town, she realised her study habits were unhealthy. She helped launch the town's Sources of Strength chapter, and has assisted in planning outreach events. She also spoke up about "the dog-eat-dog" competition that still persists at the high school.

Homework remains heavy, students said, particularly in high-level classes. Class rankings may be gone, but students have a pretty good sense of where they stand. And while there has been talk of a later start time to the day so students can get more sleep, the idea is on hold.

In December, when early decisions came in, Emily found she was deferred to the regular admissions pool by Yale, her top choice. Parents on WeChat were more sensitive this time around, but accepted seniors still bragged on Facebook.

Since then, Emily has been accepted by nine universities; rejected by three, including Yale; and wait-listed by Harvard and the University of Chicago. She is deciding between Columbia and Duke.

Through it all, she has wondered if it's worth it. "I lost out on a lot of high school," she said. She hopes that students who come after her find some balance before their time at Lexington is up.

NYTIMES