He joined a gang at the age of 15, started taking drugs at 16, and was caught selling them a year after.

But instead of receiving five years' jail and five strokes of the cane - the minimum punishment for trafficking in Class A drugs - Wilson, who declined to give his full name, was given 27 months' probation, which he started serving at a halfway house about a year ago.

Using such sentencing options more, rather than stints in the Drug Rehabilitation Centre (DRC) or jail, are among suggestions by stakeholders and MPs to improve rehabilitation. They also suggest having ex-inmates stay longer in halfway houses, and adopting a more focused, long-term approach.

On April 4, chairman of the Government Parliamentary Committee for Home Affairs and Law Christopher De Souza tabled a motion on strengthening the fight against drugs - which 10 other MPs spoke passionately in favour of.

With more schemes to help reintegrate abusers and more DRC inmates serving the tail end of their sentences outside the centre, there has been a greater push for community support and rehabilitation.

Mr Freddy Wee, deputy director of halfway house Breakthrough Missions, said: "Over the years, the prisons have put in effort to engage in treatment programmes that help inmates deal with their addiction."

Pastor Don Wong, executive director of The New Charis Mission (TNCM), said punishment and discipline were seen as a form of rehabilitation in the 1970s. This view of rehabilitation changed in the 1990s, with more counselling and teaching of life development skills.

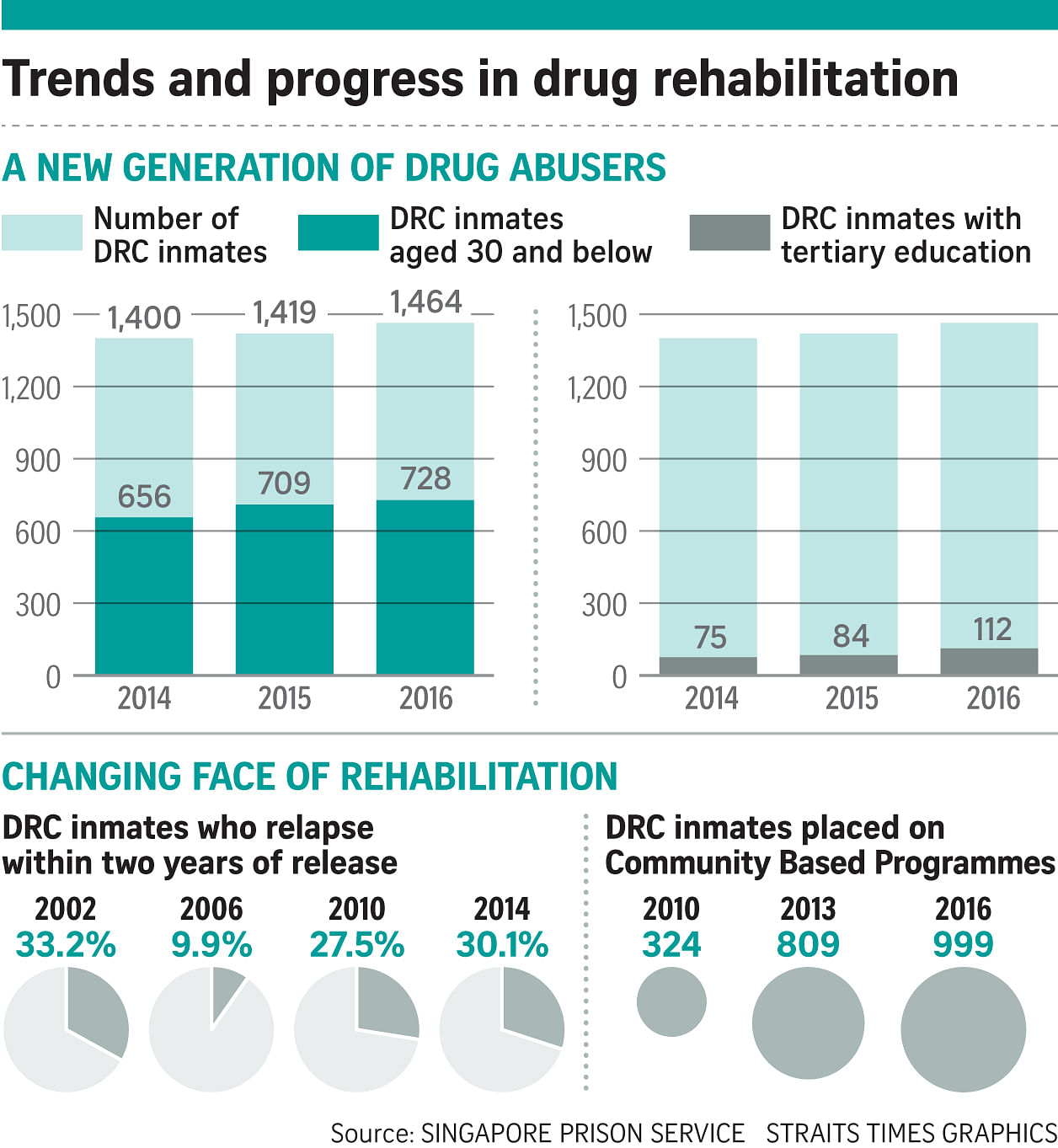

In 2011, 405 DRC inmates were placed in community-based programmes, such as the halfway house scheme which started in 1995. Under these programmes, inmates serve the tail end of their terms at home, in halfway houses, or supervision centres. The number has more than doubled to 999.

Instead of a DRC stint at the Changi Prison Complex, lower-risk drug offenders aged under 21 may also be sent for regular counselling and urine tests. DRC's regime lasts up to 36 months and targets higherrisk first- or second-time abusers.

But the days of short, sharp shock therapy for first-time abusers in the 1990s, involving alternating patterns of hard physical training and "softer" counselling to cope with difficulties upon release, are over.

Since 2002, DRCs have run counselling programmes to teach recovering addicts how to prevent a relapse. This was touted as a reason for the dip in DRC inmates' recidivism rate from 33.2 per cent in 2002 to 9.9 per cent by 2006.

But the number has since climbed back to 30.1 per cent for the cohort released in 2014.

Reasons may include the changing traits of abusers, with youth now having easier access to information and drugs online, said Mr Wee. He added: "We have to consider if the treatment now is sufficient to help them quit."

This month, Home Affairs and Law Minister K. Shanmugam warned of a new generation of drug abusers, with more students and professionals arrested last year. Such trends add on to long-standing challenges.

The rate of reoffence within two years is higher for repeat drug offenders, said MP Louis Ng (Nee Soon GRC) in Parliament. Of those serving long-term sentences of at least seven years, recidivism was 36.5 per cent for the cohort released in 2014.

He believes that a root problem is weak family bonds and support. From 2014 to last year, only about a third of DRC inmates received two family visits per month, he said.

Where family bonds can be repaired, sentences like probation may be more ideal, said experts.

Now 19, Wilson spends his days at TNCM's halfway house where his mother can visit him weekly, cheering him up with food he craves. He did not use to spend time with her like this.

"Before, all I wanted to do was take drugs. At night, when she saw me in the room (taking drugs), we would quarrel," he recalled. "The programme here helped me realise the importance of family."

Nominated MP Mahdev Mohan believes change starts upstream, asking if investigators and prosecutors should be sent for further training to inculcate a "rehabilitate first", and not a "prosecute at all costs" mindset.

Pastor Wong added that "prisons must be the last option for youth", and more can be done to get families reconnected where possible.

Noting that youth may get into drugs due to family issues, he hopes to house young abusers sent to his halfway house in a separate building starting in the next two years, creating a home-like environment to rehabilitate them.

Volunteer couples can be their "adoptive" parents, going out with them on weekends, he added. It is important to have a mentor for the youth too.

Besides focusing on the young, some experts, such as Mr Richard K, executive director of halfway house The Helping Hand, said it would be good if residents can stay beyond six to eight months. An average of 500 inmates are placed in halfway houses by the prisons each year.

"It takes at least two to three years to help a person break free," he said, relating his own experience while quitting drugs. But he added: "It may not be practical to keep a person in a halfway house for that period of time - you will end up working with fewer people (if they stay for a longer period)."

The new Selarang Halfway House, a secular, government-run facility in Upper Changi Road North, may help cater to more drug abusers. To be completed next year, it can take in around 500 ex-inmates.

He added: "Staying longer means adjustment from an addict's life, building a good foundation, and helping them be clear of the path they want to take."