Siblings Irfan Asyraf, 12, and Nur Natasha, 9, share the same birthday: August 25. They also share a developmental disorder that afflicts one in 160 children in Singapore: autism.

After Irfan was born in 2006, first-time mum Noreen Razali and dad Mohamed Jashir observed that their son was not very communicative and did not maintain eye contact.

Madam Noreen says: "Irfan preferred playing by himself. He wasn't verbal at all, and he kept spinning things repeatedly."

They compared his development to that of his cousin, who was a year older, and realised he was missing his developmental milestones.

When Irfan was two years old, his parents took him to a paediatrician, who advised them to see a specialist. They consulted a specialist at KK Women's and Children's Hospital (KKH), who observed how Irfan played and behaved. After careful analysis, she broke the news to the parents that their son had autism.

Madam Noreen, a 39-year-old trading executive, recalls: "That was my first experience dealing with autism. In fact, I didn't even know what autism was."

Both the parents' families do not have a history of autism. As they grappled with knowledge of Irfan's condition, they were advised to send him for early intervention. "That's how our journey started."

Rising rates

According to data from KKH and National University Hospital (NUH), from 2010 to 2014, there was a 76 per cent increase in the number of children diagnosed with developmental delays, learning difficulties and autism spectrum disorders (ASD) in Singapore.

While the figure may initially seem alarming, specialists cite better awareness among parents and preschool teachers, leading to early referrals for diagnosis.

But sometimes the signs of an underlying condition may not be very obvious.

Two years after Irfan's birth, Madam Noreen and Mr Jashir decided to have another child. They hoped their second baby would grow up helping with the brother's condition.

On Irfan's third birthday, Nur Natasha was born.

In the beginning, Natasha acted like most kids her age. She could talk, sing, imitate cartoon characters, and recite her 123s and ABCs fluently.

In 2013, at age four, her development regressed after starting kindergarten.

"She could not communicate well, and she started shutting down verbally. She could not keep up with all the other kids," says Madam Noreen.

Concerned, Natasha's parents again consulted the KKH specialist, who eventually diagnosed Natasha as being "partially verbal" - their second child with autism.

Madam Noreen says: "Of course it was shocking, learning that Natasha too had autism. But as Muslims, we have to accept what God has given us. So I have to be strong."

Madam Noreen was pregnant with her third child when she received Natasha's diagnosis. Although she feared for her baby's future, she says: "I didn't want to give up - I still wanted another child. Sofea came along and she was born neurotypical (not on the autism spectrum).

"Our hopes are on her to take care of her siblings when we are older."

Meltdowns

To an extent, the family's challenges are exacerbated by a lack of public awareness and empathy about autism.

She recalls the time Natasha had a major meltdown in public. The family was on holiday in Indonesia, enjoying breakfast when Natasha started wiping her breakfast knife against her shoes. Madam Noreen scolded Natasha, who started rolling on the floor and screaming uncontrollably. Other hotel guests stared, but "thankfully, there were not that many people around".

Then there are incidents closer to home. Natasha has a habit of pushing smaller girls around, both at AWWA School where she now studies, and the inclusive playgrounds the family visits. Some parents scold both mother and daughter or call them names if their child gets pushed, but Madam Noreen takes it in stride.

"My children are my responsibility, regardless of whether they are normal or have special needs," she says. "But sometimes, things happen very fast and I can't react in time. I am ready to apologise if my children do something wrong, but sadly, not everyone understands autism."

Her personal experience echoes the results from the National Council of Social Service's (NCSS) 2016 Attitude Study involving 1,400 Singaporeans, which found that public attitudes towards persons with intellectual disability or autism were less favourable than those with physical or sensory impairment.

In response to the study, NCSS launched the public education campaign See The True Me in 2016 to change public perceptions towards persons with disabilities. Pre- and post-campaign surveys conducted during the first two years of the campaign found that there was indeed a positive shift in public attitudes especially towards persons with intellectual disability and autism.

Finding the right fit

With appropriate early intervention, the right education and opportunities, children with special needs stand a better chance at developing their social, life and work skills, thus maximising their potential to contribute to society.

Every year, there are around 1,770 children per cohort with special education needs. Three in four have mild conditions like Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) or dyslexia and are able to attend mainstream schools.

The remaining 25 per cent, or about 400 children, have moderate to severe conditions like visual impairment, autism or multiple disabilities. Most, like Irfan and Natasha, attend any of 19 government-funded special education (Sped) schools run by 12 social service organisations, which cater to distinct disability profiles of students.

According to Madam Noreen, Irfan's development improved by leaps and bounds after transferring to Metta School - which caters to students with mild intellectual disability and ASD - when he was 10 years old. Irfan joined the school's signature performing and visual arts programme and has since learnt to play the ukulele. In 2017 and 2018, he topped the whole standard in mathematics.

"Metta School focuses more on academics, discipline and the performing arts. He now enjoys performing on stage, and has even played in various public events like An Extra•Ordinary Celebration at Resorts World Sentosa, in the presence of Minister Ng Chee Meng," says Madam Noreen proudly.

Daily routine

Although Irfan and Natasha attended mainstream kindergartens, they participated in the Early Intervention Programme for Infants and Children (Eipic) three times a week.

Madam Noreen credits Eipic with helping her family adapt to life with autism.

"Eipic taught Irfan and Natasha structured work systems, and educated us parents on how to teach our kids based on their learning level and preference. Some kids learn better through visuals, like Pecs (Picture Exchange Communications System)."

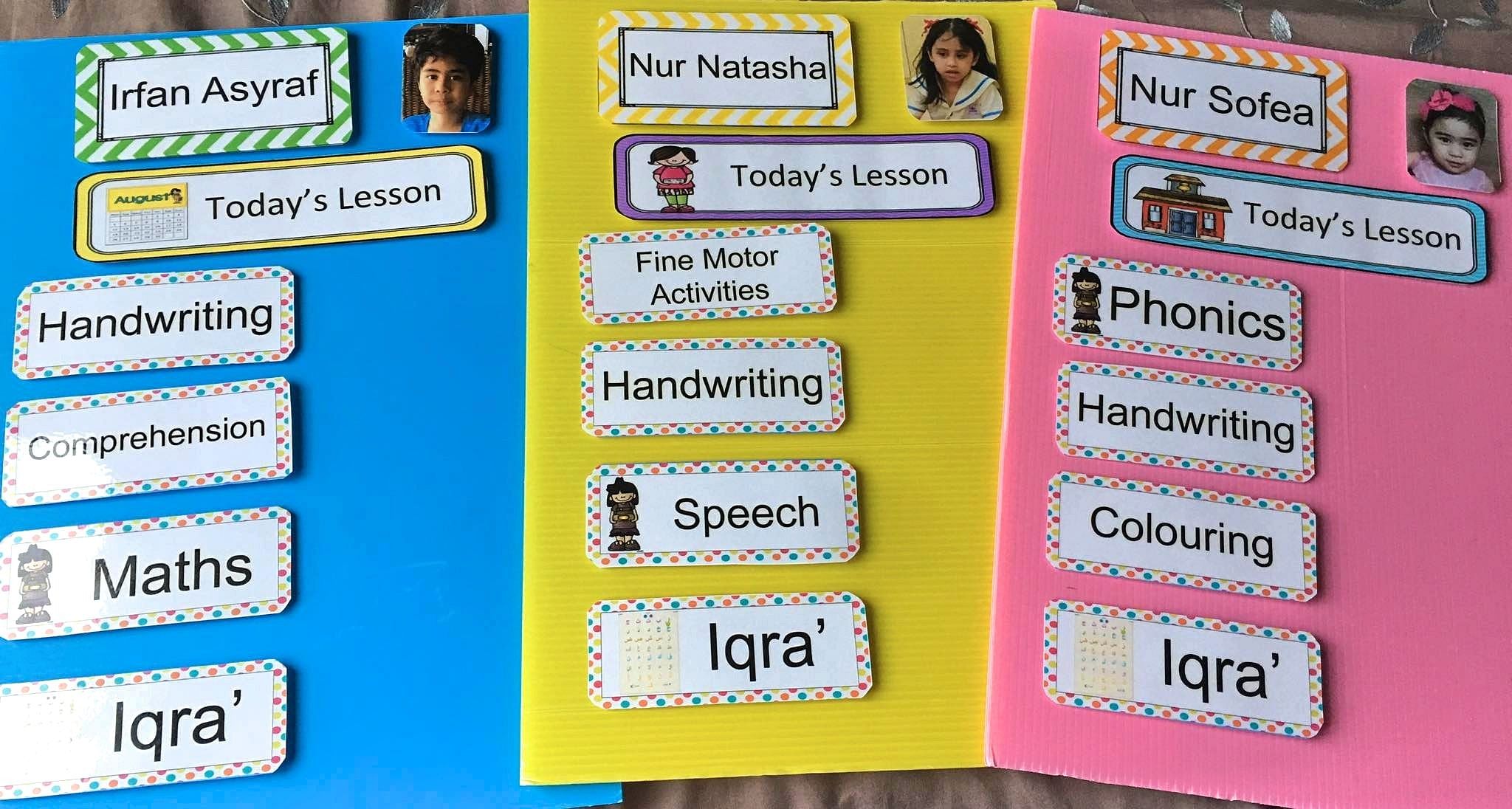

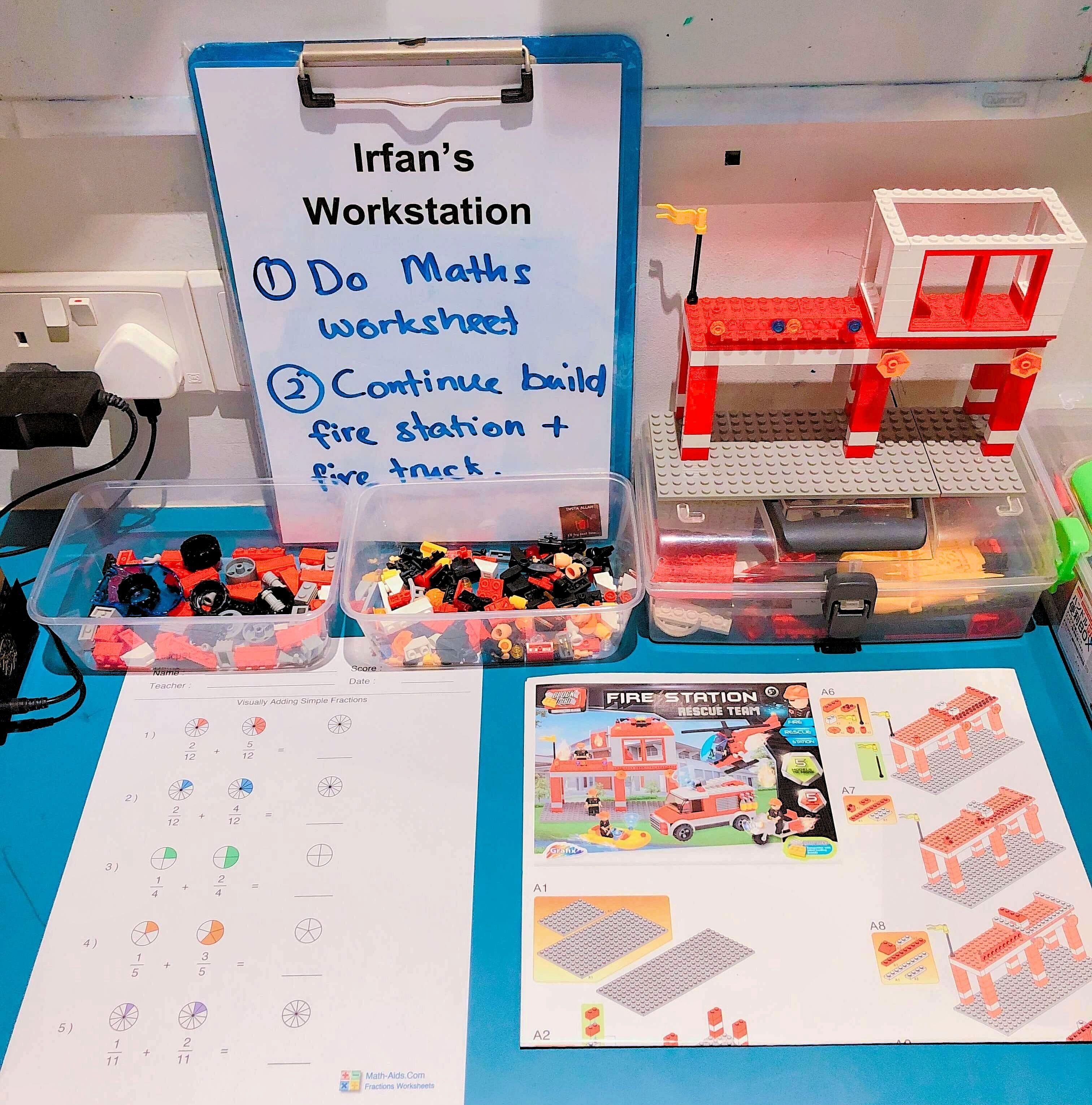

As her children prefer routine, Madam Noreen spends time every day planning their activities and study aids, getting ideas from Pinterest and various educational bloggers. Her 69-year-old mother Mariam Ibrahim comes over to help out with the kids a few times a week. "She is my Number 1 supporter," says Madam Noreen.

"My kids continually ask for more set-ups, and wait for me to sit down with them to go through the lessons together. They have never shown any hesitation in completing their tasks and always look forward to the lessons, which in turn tells me that I have achieved my goal in encouraging them to learn."

While being a mother of three in Singapore is challenging enough - let alone with two kids with special needs - Madam Noreen hopes to create awareness that working mothers like her can still play an active part in their children's growth, and that inculcating inclusivity is best started from young.

One incident she will never forget took place when Irfan was studying at Hanis Montessori, a mainstream kindergarten. Irfan sometimes pushed other kids but one boy reacted by hugging Irfan and telling him it was okay, until he calmed down.

"What that boy did was very touching, though it was only one person out of his whole class." Madam Noreen hopes more people will make the effort to be inclusive, just like that five-year-old boy.

Natasha and her sister Sofea playing at the Pasir Ris Park inclusive playground. PHOTO COURTESY OF NOREEN RAZALI

Natasha and her sister Sofea playing at the Pasir Ris Park inclusive playground. PHOTO COURTESY OF NOREEN RAZALI