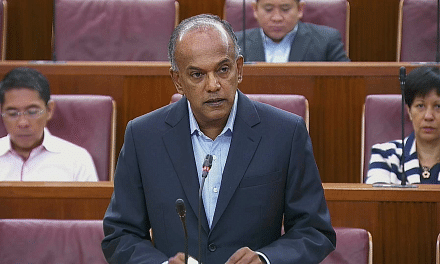

SINGAPORE - A proposed law to fight fake news was read for the second time in Parliament on Tuesday (May 7), with Law and Home Affairs Minister K. Shanmugam opening the debate on the much-talked-about Bill.

Since it was introduced in Parliament on April 1, the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Bill has elicited concerns among the public, including over whether free speech could be limited, and if certain terms in the legislation were too broadly defined.

In his speech, Mr Shanmugam addressed five of these issues, and sought to dispel the misconceptions surrounding them:

1. The Bill gives too much power to the Government

Mr Shanmugam told the House that the Bill has narrower terms than the current law.

He said that with the proposed legislation, the minister has the power to declare that an article contains falsehoods and to ask for a correction to be carried, or for the article to be taken down. This direction is open to be challenged in court, and if the minister is wrong, he gets overruled.

Mr Shanmugam refuted claims that the proposed law creates a "new crime" of spreading falsehoods, calling these assertions inaccurate. Falsehoods are already criminalised under the Telecoms Act, which also applies to the Internet, he said.

While the fake news laws also cover the same ground of falsehoods, they differ in terms of intent.

The new laws require the individual to have known, or have reason to know, that the information was false and also that spreading it was likely to prejudice public interest. These two requirements have to be satisfied, said Mr Shanmugam.

Mr Shanmugam also debunked claims that the recourse to judicial review was not available, and that a judge could not examine the proportionality of a minister's direction, saying these assertions were wrong.

He rebutted claims that a clause in the Bill - allowing certain persons to be exempted from the law - could be used for some "sinister purpose".

"This exemption power is a common provision in many pieces of legislation," said Mr Shanmugam, listing examples such as the Executive Condominium Housing Scheme Act and Postal Services Act.

He explained that it is not possible to comply with the Act in certain instances, for reasons such as a technical impossibility, and the law has to rely on this provision.

2. The Bill will have a 'chilling effect' on free speech

Mr Shanmugam said free speech should not be affected by the proposed new laws. Rather, what is being dealt with are falsehood, bots, trolls and fake accounts.

He cited National University of Singapore law professor Thio Li-ann, who gave evidence during the Select Committee on Deliberate Online Falsehoods hearings in March last year.

Prof Thio, he quoted, made the following points on the ambit of free speech: that "not all forms of speech are worthy of equal protection", and that falsely crying fire in a crowded theatre is not protected as valuable speech.

He also cited the words from a British House of Lords judgment, which said that there is "no human right to disseminate information that is not true" and "no public interest is served by communicating misinformation".

"The working of a democratic society depends on the members of that society being informed and not misinformed. Misleading people and... purveying as facts statements which are not true is destructive of the democratic society," Mr Shanmugam said, citing the judgment.

Mr Shanmugam said that where speech does not serve the justifications of free speech, by harming the search for truth or by preventing citizens from becoming informed on issues, that does not warrant protection.

3. The definition of fact and opinion is not clear

While some have asked for the proposed law to define "fact" and state that opinions are not covered under the legislation, Mr Shanmugam said this was carefully considered but decided against.

He explained that there is a body of case law on what is fact and not fact, and that it is better to rely on existing case law.

"When there is a dispute, the matter can be dealt with in court. So how else do you decide?" he asked the House.

4. Definition of public interest is too wide

Mr Shanmugam said it is important to remember that the new law does not cover statements just because they are against the public interest. "Those statements must be false statements of fact," he added.

Some have said that the definition of what is in the public interest is too wide and the Bill should not include Clause 4(f), which relates to the diminution of public confidence in the functions of government institutions, Mr Shanmugam said.

He said that online falsehoods seek to break down trust by attacking institutions, and it is important that the institutions are protected against them.

5. Difficult to challenge the minister's decision

Mr Shanmugam told the House that a process will be in place to allow an individual to appeal against a minister's direction. The detailed procedure will be in subsidiary legislation.

But he gave an overview of the process:

(a) The individual must apply to the minister to cancel a direction, and a standard form will be provided online for this. The form must be sent to an e-mail address, which will be given in the minister's direction.

(b) The relevant minister must make a decision no later than two days after the form is received.

(c) The appeal to the court will have to be filed no later than 14 days after the minister decides on the application to cancel the direction. Simple standard forms that an appellant can fill out and file in court will be provided.

(d) The court will be asked to fix the hearing within six days, if the appellant attends before the duty registrar to request an expedited hearing.

(e) The documents will need to be served on the minister no later than the next day. To make it easy, an e-mail address will be provided for the appellant to serve the documents on the minister.

(f) The minister must then file his reply in court no later than three days after the documents are served as prescribed.

Mr Shanmugam said that an individual will have the opportunity to have his case heard in the High Court as early as nine working days after initiating the challenge to the minister.

The court will continue to have a general discretion to extend timelines where there is good reason to do so, said Mr Shanmugam.

Costs will be kept "very low" for individuals and no hearing fees will be charged for the first three days, while further days of hearing will be charged at the usual rate, he said.

Even so, the court will have the power to waive the fees, he added.

This should not be taken as license to abuse the process, and the courts will still have the power to deal with parties in the usual manner, Mr Shanmugam said.